- Home

- 1923 Commemoration

- Reminders of Main

Reminders of Main

Main Building, affectionately referred to as “Old Main,” was the heart of then-Elon College, housing the auditorium, several society halls, administrative offices and most classrooms. After the devastating 1923 fire, the building was reduced to rubble and virtually all of the college’s records and artifacts were destroyed.

Several historical artifacts, however, survived and are now on prominent display throughout campus, providing a visual reminder of Elon’s resilience following the fire of 1923.

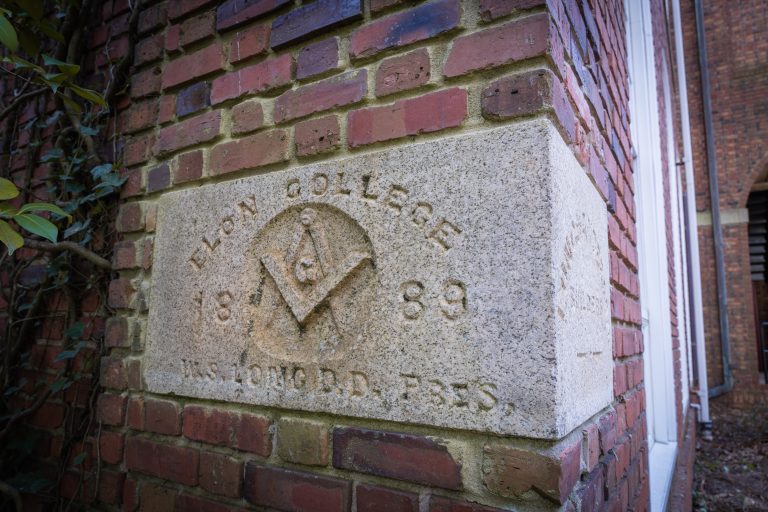

The Main Building cornerstone

The original cornerstone from Old Main can be seen at the northwest corner of Alamance Building. It is engraved with the date 1889, the name of Elon’s first president, W. S. Long; and the builders, John W. Long and William P. Anderson of Graham, North Carolina.

The cornerstone was recovered following the 1923 fire and placed in Alamance Building on the afternoon of May 28, 1923, following the graduation ceremony. A second cornerstone bearing the date 1923 is located at the northeast corner of Alamance. A copper cornerstone box encased in the cornerstone was opened on March 16, 1989, during the school’s centennial celebration. The box is on display in the Alamance Building rotunda display.

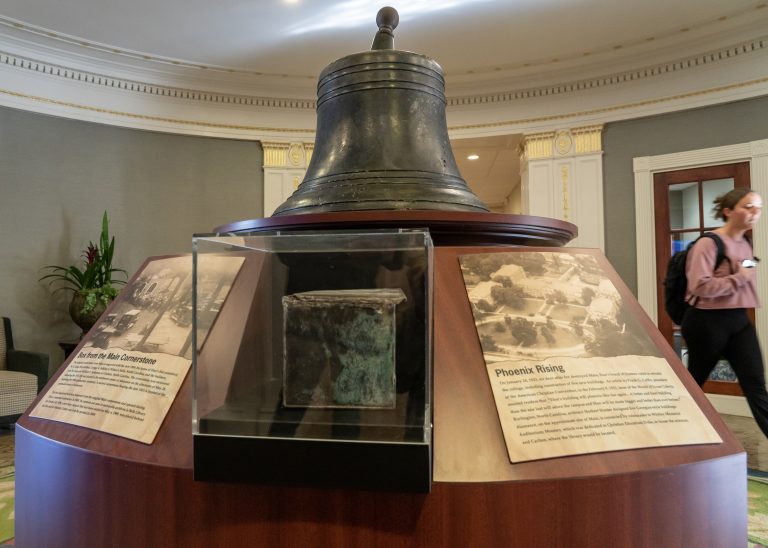

The Main Building Bell

In the Alamance Building first-floor rotunda is the charred and deformed bell from Main Building. This bell, cast by the McShane Bell Foundry in Baltimore, Maryland, was referred to in the Christian Church newspaper, the Christian Sun, on January 9, 1907, as the “new bell for the college.” The bell was used to convene and dismiss classes, call students to meals and chapel services and ring for evening curfews.

Students process through Alamance Hall to touch the Bell From Main prior to New Student Convocation, held August 20, 2022, under the oaks at Elon University.

During the fire that destroyed Main Building on January 18, 1923, the bell crashed through the four floors of the building’s tower to the ground. Intense heat caused the partial melting or “liquation” as seen on areas of the bell. Sudden chilling of these areas by water hosed on the fire created its rough appearance. The March 30, 1923, issue of the student newspaper, Maroon and Gold, reported that “The old bell…was dug from the ruins of the tower last Thursday….and it is hoped that the bell will be preserved.”

The bell has been exhibited and stored in various locations on campus including the former Church History Room in the Carlton Library Building. It was installed in a historic display in Alamance Building in July 2010.

Main Building bricks

Bricks from Old Main on display in Alamance Building.

Bricks to construct Main Building in 1889-90 were made in a brickyard operated by William H. Trollinger, who played a key role in selecting the location of the college. The brickyard was located a few hundred yards from Main, south of the railroad tracks.

Shortly after the 1923 fire, members of the campus community collapsed the fire-damaged walls into a pile of rubble. The bricks left whole were cleaned for reuse, and the broken ones were crushed and packed together to form a foundation for the Alamance Building and its adjacent parking lot.

A considerable amount of the brick cleaning was performed by the local Boy Scouts.

Some of the Main Building bricks were recovered in 2007 by a crew digging a foundation for the installation of an elevator in Alamance Building. Some of those bricks are on display in the rotunda of Alamance.

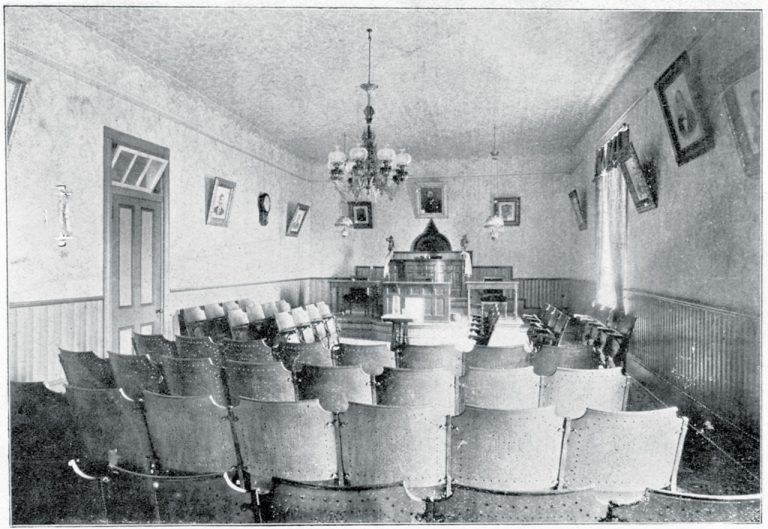

The Main Building chandelier

One of the original oil-lamp chandeliers from Main Building can be seen in the second-floor archives room of Belk Library. The chandelier first hung in the Philologian Literacy Society Hall of Main. It was removed after the college added an electric power plant in 1906 and had no need for the oil lamps. The return of the chandelier to Elon was detailed in a 2017 Magazine of Elon story by Keren Rivas ‘04:

It was the summer of 2008 and Raymond L. Beck ’75 had just retired after a 32-year career as North Carolina State Capitol historian and site manager. Sitting in the Elon Belk Library Archives Room, he was poring over documents, searching for information about Elon’s band, an organization he had been a part of during his undergraduate years.

On that particular day, he was browsing a catalog of newspapers and other sources referencing Elon compiled on 3-by-5 index cards kept in a wooden filing cabinet. As he perused the “C” section looking for information about the founding year of Elon’s cheerleading squad, his fingers suddenly paused at a card titled “Elon Chandelier in Why Not.” The weathered, typewritten entry, which cited as its source a 1958 book titled “History of Fairgrove Methodist Church,” read:

“When Charles B. Auman was a student at Elon College, he had the chance to buy an oil-burning brass chandelier from the college. This was installed near the center of the ceiling of the church [Fairgrove Methodist at Why Not]—and is intact to this day. … Later Euclid Auman wired the church and electric lights were added.”

Beck’s eyes widened. Most of Elon’s early furnishings were destroyed in a fire in 1923. Could this be one that survived? So many questions flooded his mind. He knew he needed to dig deeper, and he knew just who to call upon to help him on this journey: former Elon professor and adviser, and fellow historian, George Troxler.

More than eight years later, the two stood side by side as the chandelier returned home to Elon to adorn the very room where Beck first read of its existence. It was one of many projects the two men have collaborated on since they first met at Elon in the early 1970s and a fitting ending to the story of an artifact from the institution’s early years.

While Beck and Troxler first learned about the chandelier in 2008, it wasn’t until 2014 the two could really look closely at the clues found on the index card. Troxler got his hands on the book mentioned on the card and managed to find a photograph of the chandelier in the church at Whynot, a small rural community in Randolph County an hour away from campus. While the church is no longer an active congregation, the building and cemetery are cared for by the Whynot Memorial Association. He also was able to match it to a photo in the Elon archives from 1901 of the Philologian Literary Society Hall, one of three literary society halls that once were in the Main Administrative building, or “Old Main” as it’s often called, which was destroyed in the 1923 fire. Elon built a central power plant in 1906, bringing electricity to the campus. Auman attended Elon in 1900-01, but his sister was a student when electricity came, which is how he likely found out the college’s oil-burning lighting fixtures would no longer be needed, Troxler says.

Beck sent both photographs to two experts on 19th-century interiors. They both agreed the chandeliers in the two photographs were the same model—an eight-lamp Bradley & Hubbard Model #613. With all the evidence in their favor, and with the support of Beck and his wife, Deborah Hatton Beck, Elon purchased the chandelier and replaced it in the Fair Grove Church with an identical six-lamp model #613. Both chandeliers went through a rigorous restoration process by Jefferson Art Lighting in Ann Arbor, Mich.

The chandelier was restored according to its original paint scheme and upgraded with reproductions of the original hand-blown opalescent shades, glass chimneys, shade holders, perforated central draft burners and hand-spun brass oil fonts.

In October 2016, after nearly 110 years of being absent from campus, the chandelier returned to illuminate the Archives Room in the second floor of Belk Library. During a dedication ceremony, Beck, who saw the project as an opportunity to reconnect his class with Elon’s early history, asked that the chandelier be dedicated in honor and memory of all members of the Elon College Class of 1975. “The miracle to me is that Elon converted to electricity in 1906, which led to the chandelier’s removal and ensured its long-term survival,” Beck says. “The history of Elon can really be told through its artifacts and thank goodness we have this single pristine artifact from Old Main that we did not think, nor anyone thought, would ever be found and returned to campus.”