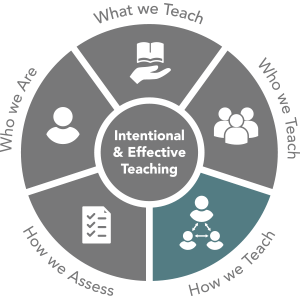

How do we teach?

How do we teach?

On a day-to-day basis, there are many things faculty can do, and not do, to increase the odds of all students feeling welcome in our classes and having a good chance of succeeding.

In addition to the general practices below, we can think about setting up an effective classroom environment, creating policies and syllabi, facilitating discussions/perspective taking, handling difficult moments, stereotype threat, (curriculum design) and student experiences.

Helpful Practices

Assume students in your classroom are diverse in a number of ways, including ways you can’t see, which might be related to national origin, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, disability, sexual orientation or gender identity, spiritual beliefs, or many other possibilities.

- Don’t just follow the law in making accommodations for students with documented disabilities. Be an ally in students’ learning. Elon’s Disabilities Resources Office can help you understand faculty rights and responsibilities.

- Submit information about required readings and materials (book orders) as early as possible so that students with financial need can explore lowest-cost options and those with certain disabilities can get access to books that have been recorded.

Frame course content and skills as “learnable.” Be explicit with all students about the learning strategies (i.e. practice problems, study groups, multiple drafts, etc.) that research has shown to be effective in mastering your course material. It can be helpful for students from previous semesters to share the strategies that worked for them.

- Try to remember what it was like to be a novice in your field – because students new to college or a discipline won’t learn as quickly as an expert or more experienced students.

- Share narratives of struggle before success. Sometimes students think faculty were always amazingly smart and talented and didn’t have to struggle to master material or overcome hurdles. Let students know you if you personally faced difficult circumstances and/or made mistakes and learned from them.

Hold students to high standards, and devise instructional strategies to support learning and encourage student risk-taking. For example, give students low-stakes practice in necessary skills, and provide timely formative feedback on their performance. Break big projects into steps.

- Think in advance about how you want to handle difficult moments.

- Assign students to heterogeneous study or project groups (diverse in multiple ways). They have been shown to help many kinds of students with various intellectual tasks and problem-solving skills. In addition, some studies suggest that heterogeneous groups more readily consider multiple perspectives and sometime generate higher quality ideas and solutions. Help them understand why you are assigning collaborative work and the expectations you have for how they should contribute to that collective work. They might need some assistance in negotiating the challenges of working in teams.

Take a strengths-based, equity-minded approach. Although students may bring specific challenges based on their background or identities, they also bring to your course unique experiences, characteristics, and skills, as well as differing reactions to course material.

- Learn more about the experiences of different students and about stereotype threat.

- In discussion-based courses, think about how insure that varying points of view are considered and students take one another’s ideas seriously. Make eye contact with everyone in all parts of the room during class. Be even-handed in who you call on and how you respond to student comments. If you’re unsure about how well you succeed, ask a colleague to observe you.

Check in and invite students to give anonymous feedback about the class climate (through a quick survey on-line or on paper. And/or ask CATL to help you find out with a mid-semester focus group.

During Class

Treat each student as an individual. Address all by their preferred names, pronounced correctly. Ask students to share their gender pronouns when they introduce themselves so that any confusion or ambiguity is eliminated. Show interest in them and their well-being. Ask students to refer to one another by name, too.

Use respectful and inclusive language. If you aren’t sure what constitutes respectful related to gender, race and ethnicity, religion, disabilities, sexual orientation, etc., you can learn.

- Start by consulting guides with general suggestions for multiple groups or search for guides for journalists related to a specific group of people (e.g., National Association for Black Journalists or National Center on Disability and Journalism).

- Harvard’s Professional Development Division shares suggestions for “Inclusive Language in Four Easy Steps,” and Maryland’s Student Union describes some common phrases that can offend some people.

Use structure and transparency to improve learning, engagement and a sense of belonging. Research suggests that using structure in course design and in-class tasks helps all students, including those from historically marginalized groups.

- Clarify course expectations, such as what constitutes “good class participation” in your course, so that students have the same understanding that you do – about everything from raising hands and consulting laptops to ground rules during class discussions. Professors in other courses or fields may well have different assumptions from you (and so might international students or students who are the first generation of their family to attend college).

- Share an outline and/or goals for each class meeting and save time at the end of class so that you or the students can summarize and/or reflect upon the main ideas.

Assignments and Feedback

Design transparent assignments – ones that are clear about the purpose, tasks, and criteria by which they’ll be evaluated. Read the research on transparency and learn more about suggestions for how to be transparent.

- While designing an assignment, consider using the Anonymous Writing Assignment Feedback service from the Elon Writing Center to get feedback on its clarity.

Communicate instructions in more than one way, when possible – choose a couple such as oral announcements in class, a handout, something written on the board, something posted in Moodle, or an email.

Discuss assignments with students before they are due and to get them to really grapple with or show they understand the expectations. Consider sharing annotated examples of strong and average work.

Grade student work anonymously, when possible (that is, without knowing which student’s work it is). This will ensure both the perception and the reality that you have been unbiased while evaluating the work.

Give feedback that is honest and constructive but also supportive; make clear that you believe students are capable of meeting the high standards.

Use mid-semester assessments as a time to check in with students who are struggling. Consider using e-warning as a way to alert a student’s academic advisor that a student may need some support.

Physical Space

Arrange your classroom to meet your pedagogical needs. Move chairs into a circle for discussion, rows facing one another for debate, facing front for presentations, and out of the way when students are “taking a stand.”

Maximize students’ capacity to learn. For example, make all sure students can see things on the board or screen and hear presentations or audio (ideally videos have closed captioning).

Dig deeper

- Consider this list of behaviors to avoid in order to establish an inclusive classroom.

- Download the Inclusive Teaching Guide from Columbia University’s Center for Teaching & Learning.

If you are an Elon faculty member and want to know more or discuss these strategies, contact CATL at x5106

Works Cited & Resources

Susan Ambrose, et al., How Learning Works: 7 Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching. Jossey-Bass, 2010.

Alan Brinkley, et al., Chicago Handbook for Teachers, 2d edition, 2011, chapter 10.

Barbara Gross Davis, Tools for Teaching. 2d edition, John Wiley and Sons, 2009.

Durham District School Board, “Guidelines for Inclusive Language.”

Carol S. Dweck, Gregory M. Walton, and Geoffrey L. Cohen, Academic Tenacity; Mindsets and Skills that Promote Long-Term Learning. Seattle, WA: Gates Foundation, 2011.

Marilla D. Svinicki, “Student Goal Orientation, Motivation and Learning,” IDEA Paper #41.

Steven Stroessner and Catherine Good, “What can be done to reduce stereotype threat?” Reducing Stereotype Threat

Franklin Tuitt and Lois Reddick, “Stereotype Threat and Ten Things We Can Do to Remove the Threat in the Air,” To Improve the Academy 26.

Mary-Ann Winkelmes, “Transparency in Teaching: Faculty Share Data and Improve Students’ Learning,” Liberal Education 99, 2, Spring 2013.

Women in Science & Engineering Leadership Institute, “Benefits and Challenges of Diversity in Academic Settings.”