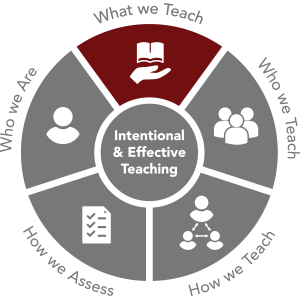

What do we teach?

What Do We Teach?

Our content – the topics, materials, and key ideas, ways of thinking, and skills – is at the heart of our courses.

As we think about incorporating content about diverse groups of people or issues related to equity, we should aim to do more than simply adding a day’s content, a single new reading, or a guest speaker. Instead, we should incorporate the content as part of a coherent course design for our specific disciplinary and course context, and include one or more DEI-related learning outcome to our syllabus.

Our Goals

Good course design always begins with a clear sense of our goals for what students will learn.

Happily, content about fairness, justice, and the many types of human diversity often aligns well with instructors’ disciplinary goals related to analyzing situations, texts, or data, comparing or applying theories and concepts, considering implications, and/or dealing with complexity or culture.

It also complements common learning goals related to building students’ skills in perspective-taking, conducting research, dialogue, reflection, expressing ideas, or communicating across difference.

Specific content looks different in different fields. For example, some sample topics and goals related to race and racism include:

- A marketing or public relations course might look at examples of companies that respectfully worked with different racial communities as well as cases of harmful or disastrous interactions.

- Psychology courses can teach concepts like implicit bias, stereotype threat, or the stages of racial development and the complexity of individual identity.

- Education courses might ask students to understand the critiques of standardized tests and the types of resilience exhibited by Black, Latinx/hispanic or mixed-race students in Title I schools.

- Biology courses can teach that racial categories are weak proxies for genetic diversity and how inaccurate assumptions about genetic differences between people have fueled racist beliefs.

- An Environmental Studies course might teach how poor communities, rural communities, and communities of color are disproportionately burdened with health hazards.

- Health-related courses might teach the roots and implications for unequal access to medical treatments, as Professors Stephanie Baker and Yanica Faustin do in Elon’s Health Equity and Racism Lab.

- Any research methods course can contextualize the requirements for IRBs by using the Tuskegee syphilis study to illustrate both race-based exploitation and some Black people’s mistrust of researchers.

- Political Science courses might study the experiences of African American people in the criminal justice system or successful examples of racial communities organizing for change.

- Sociology courses might teach students how race is socially constructed, differences between institutional and individual racism, or the intersections of various kinds of power.

Learn more about teaching about race and racism.

Naturally, it may make sense in certain courses to focus on other types of human difference – e.g., that related to gender, socioeconomic class, religion, national origin, abilities/disabilities, sexual orientation, or others.

- Economics courses can have students analyze for the ways various factors affect and intersect (for example by studying income data for Black men, Latino men, Asian men, white men, gay white men, and the same groups of women).

- Religious Studies courses can compare traditional beliefs and contemporary debates within various religions, denominations, and sects related to gender and sexuality.

- Engineering courses can teach universal design principles and assess the degree to which they have been adopted and effectively meet the needs of people with various physical disabilities.

Whichever groups you are focusing on, it’s best to avoid oversimplification, stereotypes, and tokenizing.

Some instructors teach a course in which it may seem difficult to infuse content about diversity or equity into one or more learning goals. However, even in these courses, it’s possible to adopt at least one DEI-related goal, since students in any major benefit from learning things such as:

- How recent scholarship may have changed the discipline or profession in recent years;

- Current conversations about diversity and fairness in the field;

- Contributions made to your field by scholars from historically underrepresented groups;

- Professional ethics related to fairness, culture, and aspects of a person’s identity; or

- What an inclusive lab, gallery, classroom, or workplace looks like.

Thanks to their contemporary relevance, these topics might motivate your students, and they serve as a signal of welcome for students who may hail from traditionally underrepresented or underserved groups. DEI-related knowledge and skills increase students’ chances for future success, and they can help students learn about themselves or affect change in workplaces or communities.

Materials

Our choice of materials has enormous influence on what students learn both inside and outside of class time. Readings, cases, data sets, sources, films, podcasts, etc. should be chosen to meet our learning goals.

Our materials should be accessible for our students. They should also be appropriate for the course level, and it should be clear how students can find and use them (especially important if new technology is involved). We can be inclusive by aiming for quality resources that are as affordable as possible for students with limited economic means, and accessible for students with disabilities (i.e., videos with captioning, photos with alternative text, files that are suitable for a screen reader, links that are sensibly named, etc.).

Ideally, we’ll select readings whose language is inclusive, free of stereotypes, and respectful (or if it is not, we can signal our dissatisfaction with that). Where possible, we’ll use sources that were created by members of groups being discussed, not just about them. (If that’s not possible, it might be worth an exploration into why not.)

When considering sources and materials for our courses, Lee Ann Bell and her colleagues encourage instructors to ask themselves:

- Whose experiences do the materials focus on?

- Whose perspectives are included?

- Whose perspectives aren’t included, and what can be done about that?

- Who are the authors/creators of the work?

- What is the race, gender, or other aspects of identity of the experts whose ideas we ask students to encounter?

Whenever we use examples or metaphors in class or make connections to real-world situations, we should consider whether we are including ones related to various types of people, not just the majority. That’s also true for the projects we have our students do. As Ambrose and colleagues note, “Just as important as those [examples] used are those omitted, because they all send messages about the field and who belongs in it” (179).

Communicating our Goals

Whatever our specific goals, we need to help students understand why they are important to our course, our discipline/field, and us as instructors. Research suggests that the cues we send early in the semester make a big difference, especially for students from marginalized groups who may be concerned about belonging, but also for all students.

The syllabus is one important place where we communicate what students our going to learn and which materials they’re going to encounter. It’s also one place where we signal our values related to diversity, equity, and inclusion. See more about building an inclusive syllabus.

How to Go Further

If you want some inspiration or assistance, you might try one or more of the following:

- Investigate what experts in your field/discipline are doing to incorporate more or new DEI-related content into their courses.

- Collaborate with your disciplinary or interdisciplinary colleagues about useful resources and materials, effective strategies, and meaningful learning goals.

- Talk with a CATL consultant.

You can also partner with a few colleagues to redesign your courses and apply for support from a CATL Diversity and Infusion Grant. Colleagues from many departments, including Math and Statistics, Strategic Communications, Performing Arts and Music Theatre, Finance and Economics, Exercise Science, Health Sciences, and Poverty and Social Justice have recently been awarded grants. See examples of what faculty have done.

Of course, great goals, materials, and syllabi aren’t enough. We also need to think about how we teach – how students will engage with the material before and during class, and how to set up a class climate where all our students have a chance to participate in intelligent and respectful ways.

Works Cited & Resources

Susan A. Ambrose, et al. How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons, 2010.

Lee Anne Bell, Diane J. Goodman, and Mathew Ouellett, “Design and Facilitation,” chapter 3 in Maurianne Adams and Lee Anne Bell, with Diane J. Goodman and Khyati Y. Joshi, Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice. 3rd edition (Routledge, 2016).

Columbia University Center for Teaching and Learning, Guide for Inclusive Teaching at Columbia.

Claude Steele, Whistling Vivaldi; How Stereotypes Affect Us and What We Can Do (Norton, 2010), 133-151.