- Home

- Academics

- Communications

- The Elon Journal

- Full Archive

- Fall 2023

- Fall 2023: Megan Curling

Fall 2023: Megan Curling

Radical Social Media Managers: How Thai Activism Group Thalufah Used Instagram to Organize Under Strict Lèse-majesté Laws

Megan Curling

Journalism and Public Health Studies, Elon University

Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements in an undergraduate senior capstone course in communications

Abstract

In summer 2020, political discontent in Thailand escalated once again, following a history of student activism and the 2014 military coup that brought Prayut Chan-o-cha to power as the country’s prime minister. A surge in protests led to the creation of several activist groups, including the pro-democracy, student-led group Thalufah. Through quantitative analysis of 119 captions, this research explores how Thalufah harnessed Instagram two years later to organize supporters in the face of a speech-limiting constitutional monarchy. Findings indicate that Thalufah most frequently presented their primary goals: rewriting the constitution, replacing the prime minister, and abolishing the strict lèse-majesté laws outlined in section 112 of the criminal code. Coding revealed that to underscore these goals, the group often invoked feelings of anger and used culturally informed methods to call followers to act. This research highlights the work of Thalufah while addressing a gap in the literature regarding Instagram’s role in Southeast Asian activism.

Keywords: Thailand, Instagram, student activism, pro-democracy, speech limitations

Email: mcurling@elon.edu

1. Introduction

While known as the “land of smiles,” Thailand is also known internationally for its history of coup culture. Since adopting a constitutional monarchy after a coup d’état in 1932, the country has seen nearly constant uprisings in response to political practices (Farrelly, 2013). In the midst of the Vietnam War, which disrupted the majority of Southeast Asia throughout the mid-20th century, a shift toward left-wing ideals led to the country’s first high-impact student protests (Anamwathana & Thanapornsangsuth, 2023). Beginning with the fall of Prime Minister Kittikachorn, each group of students operate with varying levels of success under strict lèse-majesté laws, commonly known as section 112, which harshly limits criticism of the Crown, making political activism difficult (Criminal Code, n.d., section 112).

Following the 2014 military coup that instated Prayut Chan-o-cha as prime minister, political unrest gradually increased before coming to a head during summer 2020 (Ganjanakhundee, 2021). Thousands of students protested the government, forming new activist groups around three central goals for change: replacing the prime minister, rewriting the constitution, and abolishing section 112 from future legal codes (Prachatai, 2020). One such group, Thalufah, formed from this movement and has since become a major advocate in the push for democratic change in the country. Three years later, the group remains active.

This research investigates the way that leaders of Thalufah, facing difficulty organizing in-person due to section 112, used Instagram as a means of communicating goals with its followers. The study analyzed 119 captions posted during summer 2022 on the group’s account to understand how organizations, even in restrictive regimes with repressive legislation such as lese-majesté, can use social media for activism purposes. Through quantitative coding, these captions were split into three major categories and seven subcategories, establishing clear themes consistent with the group’s goals.

Background

Constitutional monarchy and lèse-majesté laws

In 1932, Thailand abolished its longstanding absolute monarchy in the midst of the Siamese coup d’état, moving into a constitutional monarchy modeled after the United Kingdom’s. Nearly 100 years later, the country has seen 19 coup d’états and 20 constitutions, the most recent in 2017 (Panaspornprasit, 2017). Despite all of these updates, lèse-majesté has remained in each edition.

This concept, translating directly to “injured majesty,” describes a defamation law outlined in Thailand’s penal code that states, “Whoever defames, insults, or threatens the King, the Queen, the Heir to the Throne, or the Regent, will be punished with a jail sentence between three and fifteen years” (Criminal Code, n.d., section 112). Although these lèse-majesté laws remain in place, strides were made toward a participatory democracy in the 1997 “people’s constitution.” This edition established “constitutional mechanisms to secure accountability of politicians and bureaucrats to the public” (Klein, 1998, p. 4). Following the ratification of the document, the country entered a period of democratization and there were less than five cases of lèse-majesté annually (Merieua, 2019).

In a major backtrack for democracy, however, the 2007 constitution was published with strong limits to the electoral process (Ockey, 2007). In the following years, incidence of lèse-majesté cases increased by 1,576% (Merieua, 2019). According to the United Nations, in the time after the 2014 coup and preceding the 2017 constitution, at least 285 citizens were investigated for violations of section 112 and in 2016, only 4% of those charged did not receive a jail sentence (2017). With this rise in persecution, the UN issued a follow-up press release condemning the country stating, “we are profoundly disturbed by the reported rise in the number of lèse-majesté prosecutions since late 2020 and the harsher prison sentences” (2021, para. 6). No changes have been made to 112 in the three years since.

Neher says this history of constitutional change and coup d’états in Thailand is best understood as “an unpatterned, ad hoc event dependent on changing allegiances and power advantages held by various elite groups, such as politicians, bureaucrats, capitalist business leaders, and military officers” (1992, p. 585). This lack of consistency has created difficulty for scholars trying to understand the domestic history of Thailand, leaving most with the broad acceptance that the country is simply a steward of “coup culture” (Farrelly, 2013).

Past student protests

In the post-Vietnam war era, Thailand existed under autocratic military rule, which brought expansion to higher education opportunities, but also created severe limitations surrounding political expression. This unique combination led to a rise in left-wing student activism across the country and pressure on the government (Anamwathana & Thanapornsangsuth, 2023).

The first student victory was achieved on October 14, 1973, when King Bhumibol Adulyadej announced the resignation of PM Kittikachorn following eight days of a student-led movement (Musikawong, 2006). While this success led to more calls for democracy, neighboring countries Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam all fell to communist regimes in 1975, creating anxiety amongst the Thai public. On October 6, 1976, Thai military opened fire on roughly 2,000 student protestors at Thammasat University. Witnesses reported that the paramilitaries shot, hanged, beat, sexually assaulted, and robbed protestors. The death toll ranges anywhere from 45-100, with an official investigation never being conducted (Haberkorn, 2015).

After decades of disenfranchisement following the events of October 6, student movements began to regain traction across the country following the 2014 military coup in which Prayut Chan-o-cha seized the prime ministership (Anamwathana & Thanapornsangsuth, 2023).

2020 protests in Thailand

Following this rising tension, student-led protests erupted in Thailand during February 2020, reaching a peak during the summer months of 2020, and continuing through November 2021 (Ganjanakhundee, 2021).

On July 18, 2020, more than 2,500 people arrived at the Democracy Monument in Bangkok to announce three demands for the current government: an end to intimidation, dissolution of the sitting parliament, and a new constitution (“Youth Liberation,” 2020). By the end of the month, smaller gatherings had occurred in more than 20 provinces (Boyle, 2020). On August 3, more than 200 protestors gathered again at the Democracy Monument to further the three-goal agenda. While there, lawyer Anon Nampa gave a speech openly criticizing the government and calling for reform. Paul Chambers, a local professor, later commended him saying, “Such open criticism of Thailand’s monarch by non-elites at a public place within Thailand with the police simply standing by is the first of its kind in Thai history” (Reuters, 2020, para. 17).

On August 10, a 3,000-person protest occurred at Thammasat University’s Rangsit campus, declaring ten demands in expanding on the initial three from earlier in the summer.

1. Revoke the King’s immunity against lawsuits, 2. Revoke lèse majesté law, give amnesty to every persecuted individual, 3. Separate the King’s personal and royal assets, 4. Reduce the budget allocated to the monarchy, 5. Abolish the Royal Offices and unnecessary units e.g. Privy Council, 6. Open assets of the monarchy to audit, 7. Cease the King’s power to give public political comments, 8.Cease propaganda around the King, 9. Investigate the murders of commentators or critics of the monarchy, 10. Forbid the King to endorse future coups. (Prachatai, 2020)

In the same week, the largest protest since the 2014 coup took place at the Monument, with upward of 25,000 people returning to further emphasize their desires for revolution, not reform (Yuda, 2020). Closing out the summer before continuing protests, student groups presented the ten-point list of demands to the House Committee on Political Development, Mass Communications and Public Participation (Bangkok Post, 2020).

II. Literature Review

Available for consumer download in October 2010, Instagram is a photo-based social application for photo capturing, editing, and sharing, recognized widely as the first to base social networking on picture interaction (Jang et al., 2015). On April 10, 2012, Facebook bought the two-year-old company for $1 billion in cash and shares of its company (Rusli, 2012). The platform now boasts maps and videos in addition to photos, providing networking opportunities for both individuals and businesses (Yang, 2021).

Instagram and research

Prior to the growth of social media, engagement research was almost entirely reliant on qualitative narratives and quantitative surveys. However, each of these resulted in an incomplete “snapshot” of evidence (Nyblade et al., 2015). They also found that as Instagram evolved, it became popular for opinion sharing and as such, provides a rich backdrop for collecting large amounts of hyper specific data over a long period of time. This could aid in lessening the gap between traditional ethnographic methodologies labeled as incomplete. While not as popular a subject as other social media platforms such as Facebook or Twitter (now X), research about Instagram is increasing.

Instagram and activism

In 2022, Haq et al. noted the lack of multi-layered cascading on the platform, different from Facebook’s “share” or Twitter’s “retweet.” Because of this difference, Instagram users have a significantly limited capacity to efficiently share posts with other users on the application itself (Haq et al., 2022).

Research by Einwohner and Rochford suggests that because protests themselves are visually interesting events with protestors using signs, outfits, and visual cues, the use of a photo-based social media is conducive to engaging a group’s target audience of politically interested individuals (2019). Understanding these two ideas, it is important to note users’ only opportunity for sharing photos to those they do not follow is to send a screenshot off the platform. Following extensive content analysis, the authors concluded that despite this limited sharing function, the follow network created by the nature of the platform and its algorithm are “instrumental” in building social activism (Haq et al., 2022).

While research about online activism is relatively well studied in most of the world, major gaps in the literature remain surrounding East Asian usage. While activists in Western culture focus often on consumerist activism and identity politics, those in East Asia are fueled by political repression and ineffective governance (Su & Ting, 2019). Research that does highlight this context focuses on the push from activists to use social media as a visibility tool. Phoborisut (2019) discusses how Thai protestors in 2016 used multiple platforms as a means of rapidly spreading information about leader James Wong’s arrest, in spite of social media typically being used by governments for surveillance. Phoborisut also notes that within the context of East Asia, younger generations are trading traditional cultural loyalty in exchange for expressions of citizenship and strongly relying on social media to do so. This trend can be contextualized in other Asian countries as a form of media populism where the line between media figures and political figures is being blurred (McCargo, 2017). McCargo argues that while political expression is important in these countries, the tendency of Instagram and other platforms to promote partisan or ideological polarization should be noted as a potential negative to this activism.

Research question

Operating under a constitutional monarchy, Thailand has a decades-long history of student activism that peaked in the 1970s before returning in response to the 2014 military coup d’état. Reigniting conversation surrounding the constitution’s strict lèse-majesté laws, the country then saw protests in record-breaking numbers during COVID-19 lockdowns in 2020 (Ganjanakhundee, 2021). In this period, activists announced three primary goals for their protest efforts: abolishing article 112 of the constitution, rewriting the constitution that was most recently amended in 2017, and removing the current Prime Minister, Prayut Chan-o-cha from office (Prachatai, 2020).

Following these demands and subsequent efforts of achievement, several new student groups emerged in the activism scene, including Thalufah (“Piercing the sky”). This group of pro-democracy youth activists formed in the northeastern region to support local communities affected by government policies. This group has risen to the top of the protest movement within the country alongside a continued increase in social media use within the country (Degenhard, 2023). Under lèse-majesté laws, the group has become dependent on Instagram as a means for spreading its information with followers. Einwohner and Rochford indicate that this platform provides a successful interaction between poster and follower, allowing for larger audiences at one time to inform, engage, and persuade (2019).

Two years after students announced their goals and now with a consistent audience, Thalufah has grown a platform for social change despite a harsh environment that dissuades politically scandalous ideas. Based on the preceding review, this study poses the following research question: How did Thai activists in Thalufah use Instagram in summer 2022 to organize under strict lèse-majesté laws?

III. Methods

To answer this question, quantitative content analysis was performed, as it allows for large quantities of data to efficiently be categorized for comparison. To do this, captions from all posts made by the major Thai activism group, Thalufah, between June 1 and August 31, 2022, were translated from Thai to English. This time period was selected in an attempt to create distance between the data and crisis communications associated with protest groups during high-stress periods like summer 2020. By focusing on posts created two years removed from the height of protest, the data has greater potential to be reflective of routine focus and impact. This analysis was meant to understand the intention behind posts made by the group.

Translated captions were compiled from 119 feed posts within the set date range. To analyze the collected data, a spreadsheet was created and divided into categories of goals and themes that were identified during the data collection and translation. Each caption was coded for in one or more categories. When coding the data, the research was quantified based on frequency. Each caption was first screened for the three major goals set by activists in summer 2020: abolish 112, rewrite the constitution, and replace the Prime Minister.

The captions were then coded based on themes invoked, of which four major categories were revealed: anger, injustice, democracy, and education. Lastly, it was noted if the caption included a specific call to action. In this study, 112 captions mention or allude to the desire to dismantle strict lèse-majesté laws written into the Thai constitution. Rewrite captions mention or allude to a desire to rewrite the current 2017 Thai constitution. Replace captions mention or allude to the desire to remove Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha from office.

Anger captions include feelings of frustration and intense language. Injustice captions refer to a desire for change due to treatment of a person or group of people. Democracy captions refer to a desire to amplify voices in the country, often through election or gathering. Education captions seek to inform viewers of a topic or event. Action captions request that viewers act or respond in some form.

The quantitative data was collected to better understand the activism tactics used by Thalufah. To limit inaccuracies in translation and interlingual interpretation, only caption body text was analyzed. Text on the photos themselves, emojis, and hashtags used were eliminated from the sample during collection.

IV. Findings

The research method for this study was a quantitative content analysis performed on Instagram accounts from a Thai activism group’s Instagram account. There was a total collection of 119 captions coming from posts uploaded between June 2 and August 31, 2022. The captions varied in length, style, and content. Resulting data was calculated into percentages between the three sections of coded categories: 2020 goals, themes invoked, and calls to action.

More than 60 percent of coded captions referenced one of the 2020 goals (Table 1). This category includes captions related to abolishing section 112 of the constitution, rewriting the constitution, and replacing the prime minister. These comments included references to punishment for speaking against the government, disagreement with leaders, and desire for new laws – directly referencing change rather than abstract expression. Following this initial round of coding, a second round revealed frequency of subcategories. If posts reflected more than one category, they were coded in each.

Table 1: Captions within the coded category of 2020 goals

| Category | Description | Percentage coded |

| 112 | Posts referencing the abolition of section 112 of the Thai Criminal Code | 26.9% |

| Rewrite | Posts referencing the desire to rewrite the Thai constitution | 9.2% |

| Replace | Posts referencing the desire to replace the current Prime Minister, Prayut Chan-o-cha | 40.3% |

The most popular subcategory was replace, the desire to replace Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha, with 40.3% of captions referencing this goal. Most captions reference removal through advertising for a “vote of no-confidence.” Some of these captions include explicit calls for the removal with statements like, “General Prayut Chan-o-cha, as the lead figure in the new wave of reclamation plans, has to resign.” Less direct, some captions criticize the actions of Prayut in a way that encourages new leadership through statements like, “dictatorship anywhere is the same.”

The next most popular subcategory was 112, the goal of abolishing section 112 of the Thai constitution, which outlines strict lèse-majesté laws. 26.9% of captions referenced this goal. 31 of the 32 captions coded in this category directly referenced the law, like one caption that spoke of an individual detained by the government who had “4 allegations that have been reported under arrest, namely offenses under Section 112 of the Criminal Code.” The outlier in this sample referenced the law through humor, when the group released sticker designs for sale, stating that, “Each sheet is only 112!!” to purchase in Thai baht.

The least popular subcategory was rewrite, the desire to rewrite the Thai constitution to reflect less monarchical ideals, with only 9.2% of captions referencing this goal. These captions often called for a total rewrite of the constitution rather than specific references to section 112. For example, one caption included:

We must push for a bill on amnesty for people who have been damaged or affected by the implementation of government policies. Propose to dismiss unfair lawsuits by setting up a mechanism in which the public participates in scrutinizing cases that violate human rights, community rights, bullying cases and lawsuits against public silence using the jury trial.

Other captions referenced more broad political reform that would take place through constitutional amendment with statements similar to, “let the public keep an eye on the decision of the Constitutional Court.”

The subcategories of 112 and rewrite were separated as they were announced as separate goals during the 2020 protests. However, if these two were combined, they would total 36.1%, comparable to the replace subcategory.

More than 87% of captions coded invoked at least one of the four themes identified. These subcategories include captions related to anger, democracy, injustice, and education. These comments included references to feelings of frustration, encouragement of pro-democracy ideals, feelings of powerlessness, and informative sharing.

Most commonly, coded captions invoked the theme of democracy with 44.5% referencing anti-monarchical principles. This was most commonly seen in a series of posts advocating for the “vote of no-confidence” in Chan-o-cha, encouraging the democratic right of popular voting. One post discussing the legitimacy of sex workers in the country celebrated followers who “came out to organize under the democratic way.” Another post featured a caption encouraging followers to attend a parade in Bangkok, dressing up in “any democracy theme.”

In 42% of coded captions, reference was made to an instance of injustice, a time when someone experienced unfairness or an interpretation of inequity. Frequently these moments were in reference to the detention of citizens under section 112. In one caption, the group included, “other activists were forced to disappear. and justice has not been received.” In another post referencing the frequency of jailing of activists, they said “there are at least 28 of our friends in prison together.”

Education was the focus of 32.8% of coded captions, including instructive information regarding a chosen topic for followers. A series of posts about the vote of no-confidence directly addressed followers, saying, “You can follow up through the people’s page and various coalitions soon. Your voice will be sent to the house of representatives and will be counted along with the voices of MPs in the house.” This direct form of communication encourages followers to better understand upcoming situations. Similar tactics were used to inform about ongoing jailings of activists with updates like, “The case against the Democrat Party who are still not entitled to bail In terms of feelings, there is still stability with the power of ideology.”

Lastly, 27.7% of coded captions expressed feelings of anger. These posts invoked feelings of frustration and could be interpreted as aggressive. After an activist was arrested captions included statements including, “when will you be a respectable court?” and “why the previous summons was not sent to the domicile at all? But was sent to Bueng Kan police station first?” In an effort to encourage followers to participate in the vote of no-confidence, one caption included the statement, “We may lose faith in the voices in the council, desperate with the parasitic party, desperate for the constitution, desperate for justice.”

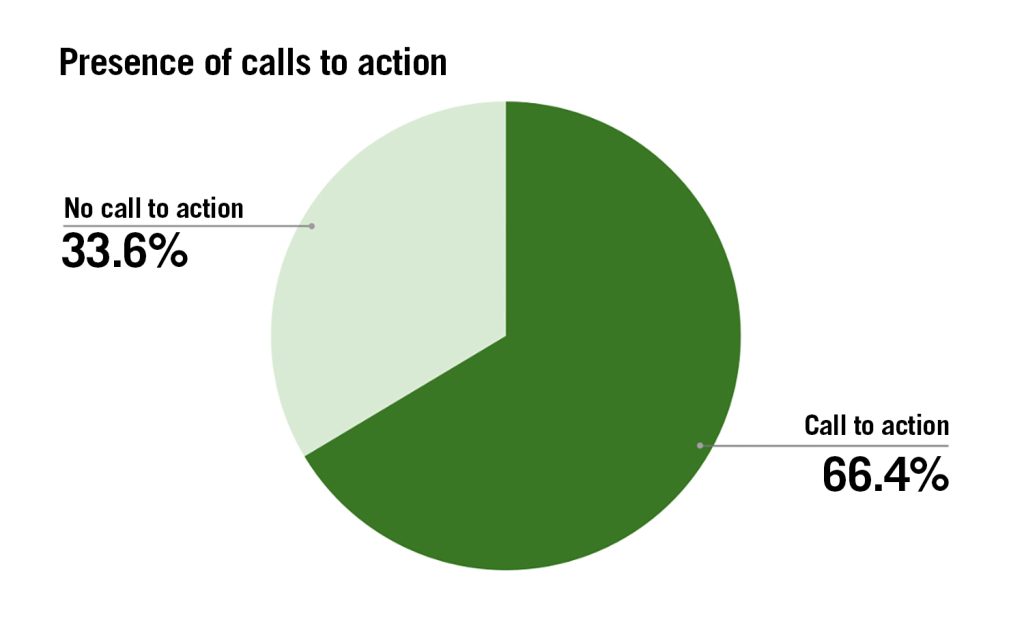

Just over two-thirds of coded captions included calls to action, a prompt designed to inspire an audience to act in a certain way (Figure 1). These captions include keywords such as “act,” “come,” and “see.” Most common phrases used were, “let’s go and talk,” “come and observe,” and “keep an eye.” These requests were often made at the end of captions, informing readers of a certain situation before asking them to participate.

Figure I: Percentage of captions that include call to action

V. Discussion

Understanding that Thailand operates under a strict constitutional monarchy with limitations on speech, the group has taken to Instagram as a means of spreading awareness without as high a risk for punishment. In 2020, student protestors announced the three goals to replace the sitting prime minister, rewrite the constitution, and abolish article 112 of the criminal code. Given Thalufah member presence in the 2020 protests, it makes sense that its posts would commonly call back upon these goals. While the low incidence of rewrite is surprising in comparison to the other two goals, it can likely be explained by the focus on the vote of no-confidence during the period of collection.

In understanding themes invoked by the posts, there was a notable gap between references to democracy and injustice as compared to the seemingly related feeling of anger. As the world has become increasingly globalized over the last several decades and higher education has become more accessible in Thailand, there have been increased calls for democratic reform. The results reflect this, with the majority of posts referencing traditional democracy and language indicating hope for change. This desire for something new and theoretically better operates in tandem with the concept of injustice, as most student protestors believe that a democratic government would significantly lessen instances of unjust treatment of Thai citizens.

Despite these aspirations for change, Thalufah strayed from frequently using aggressive or violent language in its posts. This varies from other cultures where activism is often underlined with imagery that causes madness in the viewer. While surprising, this trend aligns with Thai social culture, which in comparison to American culture, is traditionally more respectful and understanding interpersonally. Knutson et al., concluded,

Specifically, the emphasis of the high-context, collective Thai culture on social harmony and pleasant relationships strongly suggests that Thai people will exhibit high levels of rhetorical sensitivity and reflection and low levels of noble self in their interpersonal communication (2003, p. 66)

Outside of activism settings, conflicts in Thailand are avoided rather than encouraged, carrying over into Thalufah’s posting strategy.

Also initially surprising was that less than 75% of posts coming from the group called on viewers to action. Taken in the context of Thai culture, it became understandable that action posts often promoted events that were celebratory or for casual conversation, as opposed to protests or mobs. This strategy allows for the group to maintain its viewers’ attention with frequent posts despite a lack of active protesting during a given time. By producing educational content without doing so in an aggressive way, the group shares its mission and values without falling victim to lèse-majesté restrictions. Overall, Thalufah uses Instagram to reference past goals set by activists while using language that appeals to culturally-informed ideals and promotes organization when safe to do so.

Limitations

The primary limitation in this research is the difference in language spoken by the researcher and used by Thalufah. All captions were written in Thai and translated via an online database by a native English speaker. Due to limitations in time and resources, it was not possible to translate captions through a native Thai speaker. This circumstance may have led to some inherent misinterpretations in content that skewed the data. For the same resource constraints, coding was only performed by the author. Had there been a budget for this project, a second coder would have been used to ensure intercoder reliability and eliminate any accidental subjectivity.

Another limitation was the atypical occurrence of a national vote during the post range which likely increased frequency in mentions of replace in reference to voting for no-confidence in Prayut Chan-o-cha. Had the period of observation occurred without an election, results would almost certainly not focus as heavily on this category. Lastly, while 119 captions provided a significant amount of data, results could potentially be seen as more conclusive if more captions were collected and coded. However, due to time constraints, this was not possible.

VI. Conclusion

This paper sought to discover how a key protest group in Thailand presented social media posts to organize followers in a political climate hallmarked by frequent coups and lack of political speech. In an age of social media, groups have turned to Instagram as a means of reaching large audiences with minimal effort, sharing their messaging on a platform that is considered easy to navigate. Thalufah has been a primary player in protests over the past three years, advocating for political changes that support basic democratic rights like having an elected leader, laws that represent the opinions of its constituents, and the ability to disagree with the monarchy. This involvement has taken place despite major barriers to organizing in person, making its impact all the more impressive.

Based on this research, it can be concluded that tactics rooted in cultural norms and focused on education are common and would likely be expected in other Thai protest communications. Although it is understood that Instagram can play a role in successful organization efforts, there is still significantly less research into the platform’s effectiveness in comparison to X and Facebook. As Instagram and new social media platforms continue to grow, studying their capabilities will become increasingly important to support activists around the world who are underrepresented in current literature. To do this, additional research should be conducted in East Asia specifically and include results of calls to action used. While political disagreement occurs everywhere, understanding other nations’ struggles and social media’s potential to aid in human rights growth builds a stronger global community for all citizens.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Dr. Jessalyn Strauss for her ceaseless patience, from the first half-formed thought to the edited manuscript. Thanks also to my family for teaching me the importance of global citizenship and the Elon journalism faculty for teaching me how to share it with others. This research was inspired by Rungruedee Keangdapha and the villagers of Na Nong Bong who taught me what it means to fight for justice as a community.

References

Anamwathana, P., & Thanapornsangsuth, S. (2023). Youth political participation in Thailand: A social and historical overview. International Journal of Sociology, 53(2), 146-157. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207659.2023.2167381.

Bangkok Post Group. (2020). Students submit manifesto. Bangkok Post. Retrieved from https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/politics/1975175/students-submit-manifesto.

Boyd, D. M., & Ellison, N. B. (2007). Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1), 210–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x.

Boyle, G. (2020). Chiang Mai, Ubon rally against Prayut, government. Bangkok Post. Retrieved from https://www.bangkokpost.com/learning/easy/1954343/chiang-mai-ubon-rally-against-prayut-government?cx_placement=related#cxrecs_s.

Degenhard, J. (2023). Thailand: Instagram users 2018-2027. Statista. Retrived from https://www.statista.com/forecasts/1138778/instagram-users-in-thailand.

Einwohner, R. L., & Rochford, E. (2019). After the march: Using Instagram to perform and sustain the women’s march. Sociological Forum, 34(S1), 1090-1111 https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12542.

Farrelly, N. (2013). Why democracy struggles: Thailand’s elite coup culture. Australian Journal of International Affairs, 67(3), 281–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357718.2013.788123.

Ganjanakhundee, S. (2021). Thailand in 2020: A turbulent year. Southeast Asian Affairs. 335–355. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27075089.

Haberkorn, T. (2015). The hidden transcript of Amnesty: The 6 October 1976 massacre and coup in Thailand. Critical Asian Studies, 47(1), 44–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/14672715.2015.997344.

Haq, E.-U., Braud, T., Yau, Y.-P., Lee, L.-H., Keller, F. B., & Hui, P. (2022). Screenshots, symbols, and personal thoughts: The role of Instagram for Social Activism. Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2022, 3728–3739. https://doi.org/10.1145/3485447.3512268.

Jang, J. Y., Han, K., Shih, P. C., & Lee, D. (2015). Generation like: Comparative characteristics in Instagram. 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 4039–4042. https://doi.org/10.1145/2702123.2702555.

Klein, J. R. (1998). The constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand, 1997: A blueprint for participatory democracy. Retrieved from https://aceproject.org/ero-en/regions/asia/TH/AsiaFoundationThailand.pdf.

Knutson, T.J., Komolsevinb, R., Chatiketuc, P., Smith, V, R. (2003). A cross-cultural comparison of Thai and US American rhetorical sensitivity: implications for intercultural communication effectiveness. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 27(1), 63-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0147-1767(02)00060-3.

McCargo, D. (2017). New media, new partisanship: Divided virtual politics in and beyond Thailand. International Journal of Communications, 11, 4138–4157. http://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/6704.

Merieau, E. (2019). On blasphemy in a Buddhist kingdom: Thailand’s Lese Majeste law. Buddhism, Law & Society, 4, 53-92. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334480041_On_Blasphemy_in_a_Buddhist_Kingdom_Thailands_Lese_Majeste_Law.

Musikawong, S. (2006). Thai democracy and the October (1973–1976) events. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 7(4), 713–716. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649370600983360.

Neher, C. D. (1992). Political succession in Thailand. Asian Survey, 32(7), 585–605. https://doi.org/10.2307/2644943

Nyblade, B., O’Mahony, A., & Sinpeng, A. (2015). Social media data and the dynamics of Thai protests. Asian Journal of Social Science, 43(5), 545-566. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685314-04305003.

Ockey, J. (2007). Thailand in 2006: Retreat to military rule. Asian Survey, 47(1), 133–140. https://doi.org/10.1525/as.2007.47.1.133.

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (2017). Press briefing note on Thailand: Thailand lèse Majesté. United Nations. https://www.ohchr.org/en/2017/06/press-briefing-note-thailand?LangID=E&NewsID=21734.

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. (2021). Thailand: UN experts alarmed by rise in use of lèse-majesté laws. United Nations. https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2021/02/thailand-un-experts-alarmed-rise-use-lese-majeste-laws.

Panaspornprasit, C. (2017). Thailand: The historical and indefinite transitions. Southeast Asian Affairs, 353–366. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26492618.

Phoborisut, P. (2019). Contesting big brother: Joshua Wong, protests, and the student network of resistance in Thailand. International Journal of Communication, 13, 3270–3292. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/10046.

Prachatai English. (2020). The demonstration at Thammasat proposes monarchy reform. Retrieved from https://prachataienglish.com/node/8709.

Reuters. (2020). Thai protesters openly criticize monarchy. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-thailand-protests/thai-protesters-openly-criticize-monarchy-idUSKCN24Z2JY.

Rusli, E. M. (2012). Facebook buys Instagram for $1 billion. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://archive.nytimes.com/dealbook.nytimes.com/2012/04/09/facebook-buys-instagram-for-1-billion/.

Su, C., & Ting, T-Y. (2019). East Asia in action: Activist media communication in new perspectives. International Journal of Communications, 13, 3244–3249. Retrieved from https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/9553.

Thai Contracts. (n.d.). CRIMINAL CODE B.E. 2499. Thailand Law Online. Retrieved from https://www.thailandlawonline.com/laws-in-thailand/thailand-criminal-law-text-translation.

Yang, C. (2021). Research in the Instagram Context: Approaches and Methods. The Journal of Social Sciences Research, 7(1), 15–21. https://ideas.repec.org/a/arp/tjssrr/2021p15-21.html.

Yuda, M. S. (2020). Thailand’s youth demo evolves to largest protest since 2014 coup. Nikkei Asia. Retrieved from https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Turbulent-Thailand/Thailand-s-youth-demo-evolves-to-largest-protest-since-2014-coup.