- Home

- Academics

- Communications

- The Elon Journal

- Full Archive

- Spring 2024

- Spring 2024: Miles B. Vance

Spring 2024: Miles B. Vance

Frames of Death: The Rhetorical Goals of Official Social Media Posts in the Russo-Ukrainian War

Miles B. Vance

Cinema and Television Arts, Elon University

Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements in an undergraduate senior capstone course in communications

Abstract

The prevalence of social media in daily life has made a substantive impact on the fields of propaganda and population manipulation. This phenomenon has manifested most significantly to Western audiences in the context of the 2016 United States presidential election, where Russian misinformation campaigns were used to promote the efforts of eventual president Donald J. Trump. Additionally, in recent conflicts around the world, social media propaganda has been used alongside traditional propaganda as part of a mental warfare campaign. The most recent example of this can be seen in the ongoing phase of the Russo-Ukrainian War, beginning after Russia invaded the east of Ukraine in February 2022. This research examined examples of social media content posted by Russian, Ukrainian, and Wagner-affiliated social media channels and analyzed the content for rhetorical goals and devices. The study employed the analysis of two videos from each side for three different events: the fall of Bakhmut, the Kerch Bridge explosion, and the one-year anniversary of the invasion. This leads to a total of 18 individual posts, with an additional two images analyzed concerning the advent of drone video posts. The results of this study show that the most common themes of social media content were legitimization, deflection, humor, and violence. All three sides appear to use similar tactics, although Russian channels often deign to engage in posting directly violent content. The motivations of these channels are to engage the viewer and either uplift or dismay them.

Keywords: Hybrid warfare, Russo-Ukrainian War, propaganda, social media

Email: mvance5@elon.edu

1. Introduction

This research analyzes the online social media content posted during the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine, which is part of the decade-long Russo-Ukrainian War. The research revolves around three distinct entities posting videos and images of the conflict: The Armed Forces of Ukraine (ZSU), the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation (VSRF), and the Russian Private Military Contractor known as the Wagner Group. Included in the selection of Ukrainian sources are units such as the Third Assault Brigade, which is a Ukrainian military division comprised of soldiers belonging to the Azov Battalion, a far-right third-party militia in Ukraine that has been incorporated into the Ukrainian Armed Forces. The purpose of this research is to qualitatively examine the online content produced by these entities and analyze such material for elements of narrative, tone, framing, music, and internet memes, all of which construct a form of postmodern psychological warfare known as Hybrid Warfare or Information Warfare. In previous conflicts, propaganda leaflets have been airdropped to enemy combatants and civilians. The internet provides a new medium for spreading propaganda and false information, which may greatly assist a country’s war effort through influencing the civilians and soldiers of both their homeland and their opponents.

II. Literature Review

In the years since the conclusion of the Cold War, information technologies such as the internet, computers, and cell phones have rapidly advanced in ability, speed, and prevalence in daily life. It is now almost inevitable that any given person in a developed nation will be in possession of a device capable of connection to the internet. This era of hyper-connectivity creates new possibilities for the use of information in warfare. The concepts of hybrid warfare, information warfare, social media, and their roles in the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine will be discussed in this literature review.

According to Danyk and Briggs (2023), “Tools of information perception and manipulation can be used to achieve various political, economic, military, and other goals, which in some interpretations is a form of preventative defense” (p.35). The integration of such “tools of information perception and manipulation” into warfare is part of a phenomenon referred to as “hybrid warfare.” Hybrid warfare has existed as a phenomenon since the 1990s and will remain relevant in conflicts for the foreseeable future (Danyk & Briggs, 2023). Hybrid warfare is utilized by countries the world over, and it is useful because “The ambiguous nature of (hybrid warfare) and its use of ambiguous modes such as insurgency and terrorism allow a belligerent to minimalize targeting opportunities by denying the opponent the ability to utilize its advantage in firepower” (Brown, 2018 p. 62). Put simply, hybrid warfare seeks to circumnavigate material or numerical disadvantage through alternative means. These methods can include information warfare, cyber warfare, guerrilla-like infrastructure attacks, or any other number of alternative attacks on an adversary. Russia has been noted for its usage of the concept in its military interventions in Georgia and Ukraine (Brown, 2018), and this is part of Russia’s larger attempt at utilizing hybrid warfare “in its pursuit of dominance in the Eastern neighborhood” (Ratsiborynska, 2016 p. 18). This research focuses on the use of information and misinformation within hybrid warfare, particularly in the form of posts from Russian and Ukrainian sources on social media.

In the 21st century, social media is an increasingly important tool in agenda setting, which is the act of determining which issues will be important to the public (Feezell, 2018). Agenda setting on social media is particularly potent against those who are typically “uninformed” regarding political issues (Feezell, 2018). Prier (2017) identifies social media as a new and powerful tool in the field of information warfare, noting that the platforms “could be used as a weapon against the minds of the population… he who controls the trend will control the narrative – and, ultimately, the narrative controls the will of the people” (p. 81). Russia has long been a pioneer of this method, and perhaps its most visible efforts from a Western perspective can be seen in the 2016 U.S. presidential election, in which Russian information weapons systems directly targeted American users of social media websites to achieve the goal of spreading disruption, false information, and distrust (Hanlon, 2018).

Biały (2017), borrowing from Ben Nimmo, has identified four main ways in which Russia has used social media to spread misinformation and sow distrust. These are: dismissing online commentators by attacking their credibility or factual statements, distorting facts with misleading depictions and contexts, distracting the audience by arguing alternative lines of reasoning, and dismaying the audience with frightening content. This final tactic of dismay has been used heavily in the ongoing conflict surrounding the invasion, with thousands of horribly gory videos of drone bombings, civilian deaths, and other realities of war proliferating social media feeds. Ross and Rutland (2022) have identified everything ranging from “Words, tweets, TikToks, Instagram posts, drone recordings, and any other microtarget-enabling media deemed ‘view-worthy’” (p.222) as the primary “weapons” of information warfare. Ross and Rutland further urge the U.S. Army to develop “appropriate doctrinal changes related to information operations, public affairs, and cyber space operations.” (Ross & Rutland, 2018 p.222).

Russia has been extraordinarily proactive in its use of information warfare in the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War, only increasing its efforts after the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Mullaney (2022) has performed valuable work in quantifying and describing Russia’s perceived goals in their social media war campaigns, and notes that the current goal is to pressure the local population, distract civilians from facts, and actively deceive them with false information and skewed perspectives. Mullaney further explains how Russia targets users, remarking that “the Russian domestic audience remained the most important target throughout the war… (Russia) targeted vulnerabilities within its society and sought to legitimize the war” (Mullaney, 2022 p. 199). This shows that information warfare, especially when viewed through the lens of social media, can target multiple audiences. Propaganda is no longer a home effort, as the same posts can be viewed by both Russian patriots and Ukrainians who may doubt their government’s legitimacy. Indeed, a popular topic addressed by Putin’s regime seems to be the supposedly Nazi-infested parliament of Ukraine. This rhetoric is likely used because it targets both Russians and Ukrainians as an audience and appeals to a commonly recognized evil entity.

One interesting aspect about the Russian use of hybrid warfare in the ongoing conflict post-invasion is that Russia has not used cyber-attacks to target the internet. Russia has occasionally targeted civilian power infrastructure and governmental infrastructure, but in a much more restrained and noninvasive way than theorists of cyber warfare have previously predicted (Lin, 2022). This lack of direct attack could be because Russia lacks the capabilities to engage in cyber warfare on a scale previously approximated, but it is far more likely that Russia wants Ukrainian civilians and soldiers to continue to have access to power and internet so that those individuals can be exposed to the Russian information warfare systems. If Kyiv were to “go black,” the Russian efforts at dominating social media would be worthless. It is possible that Russia will use cyberattacks to target substations and internet/cell towers in a retreat scenario, as was seen with the Chernobyl area. However, this remains to be seen, and for the time being, Russia appears perfectly content to keep Ukrainian internet active.

The current field of research is exhaustive in its examination of Russia’s use of hybrid warfare, including the aspect of information warfare on social media. However, the existing work has not fully examined Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the latest iteration of the Russo-Ukrainian War. Furthermore, current research neglects to consider Ukraine’s efforts at social media information warfare and related hybrid warfare efforts. This may be because Ukraine has largely mirrored Russia in its efforts, but this research seeks to investigate Ukrainian voices alongside Russian ones. Finally, the current field of research has given little consideration to the rhetorical devices employed by wagers of information warfare on social media platforms. This research seeks to fill the gap in existing study by providing a current and relevant investigation of the unique rhetorical devices employed in social media content by Russian, Ukrainian, and third-party forces.

Research Questions

The following questions will be the focus of this research project:

RQ1: What specific methods and rhetorical tools are used by Russian, Ukrainian, and PMC forces to frame the war in video social media content?

RQ2: What similarities and differences exist between Russian, Ukrainian, and third-party forces’ methods and video content?

RQ3: Why do these forces make these rhetorical decisions? What benefits might their unique utilizations of framing offer in advancing their narrative?

This research is timely because it seeks to analyze an ongoing conflict for the rhetorical goals present in social media videos. Previous research has examined Russia’s engagement with hybrid and information warfare, but it has not fully examined the latest iteration of the Russo-Ukrainian War beginning with the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Furthermore, existing research does not tend to focus on the specific visual and rhetorical elements utilized in propaganda posts. Finally, the current scope of research studying information in the Russo-Ukrainian War focuses greatly on Russia but fails to adequately explore Ukrainian and third-party attempts at propaganda and information warfare. For these reasons, this research addresses important and neglected topics in the fields of information warfare and propaganda.

III. Methods

This research uses qualitative content analysis to identify the specific visual, aural, and narrative elements comprising Russian and Ukrainian attempts at propaganda. Rosenberry and Vicker (2021) define qualitative content analysis as a form of research where “the researcher ‘interacts’ with the documentary materials to analyze the documents and better understand their meanings in context” (p. 228). Qualitative content analysis is useful for this research project because it allows the direct analysis of Russian and Ukrainian social media posts in the context of the larger conflict, which is part of a war stretching back almost a decade. Qualitative content analysis also allows the researcher to examine these posts within the content of the surrounding battles and “flow” of the conflict in the days and weeks leading up to each post, which influence the ways in which these entities choose to portray the conflict. Rosenberry and Vicker (2021) also state that the specific content selected for investigation must be “selected for conceptually or theoretically relevant reasons” (p. 228).

This project has selected videos posted in the aftermath of three events: one Ukrainian victory, one Russian victory, and the one-year anniversary of the invasion in February 2023. These have been selected to ensure a wide range of content to understand the ways in which each side frames (or ignores) victory and defeat. Deliberate selection within specific events is being used instead of simply selecting random posts to ensure that rhetorical elements are present in the videos. By remaining selective in determining the sample, this research attempts to avoid any indeterminate elements, such as leaked videos or heavily reposted and re-edited content. In this project, the specific qualities that are examined include the video, audio, editing, tone, and overarching narrative of each post. All these elements combine to create the unique profile of each post, which in turn aims to form or modify the audience’s perception of the war.

The specific social media websites that are used in this research include, but are not limited to, Twitter, Reddit, Telegram, 4Chan, and WhatsApp. Telegram and 4Chan have been selected because they are the most accessible “Western” based websites that still host pro-Russia propaganda videos. Telegram especially appears to host many Russia- and Wagner-affiliated channels. Twitter, Reddit, and WhatsApp are useful sources because they serve as content aggregators, with several pages, such as Reddit’s r/CombatFootage, dedicated to reposting war footage and propaganda for the purpose of increasing public knowledge or spreading a narrative. However, many videos and images found on Reddit, Twitter, and WhatsApp seem to originate from Telegram, so videos selected from these sources will be provided in their original Telegram context. Many mainstream social media platforms, such as Facebook or TikTok, have strict policies forbidding violent content, making analysis on their platforms difficult. To ensure a degree of randomness in sampling, two posts from each perspective will be randomly selected from a larger pool of deliberately selected content in the aforementioned contexts (being a Russian victory, Ukrainian victory, and the invasion anniversary).

IV. Findings

This study found that there are consistent and identifiable trends in posting online content in the Russo-Ukrainian War. Table 1 below briefly outlines the typical social media responses identified after a Russian victory, Ukrainian victory, and the one-year anniversary of the invasion.

Table 1

| Ukrainian Sources | Russian Sources | Wagner Sources | |

| Russian Victory (Battle of Bakhmut, around 20th May 2023) | Ignored reports of Russian victory, sought to legitimize soldiers and capability. | Celebrated victory in Bakhmut, praised Wagner and Yevgeny Prigozhin. | Celebrated victory and praised Prigozhin, utilized memes and humor. |

| Ukrainian Victory (Kerch Bridge explosion, 8th October 2022) | Celebrated explosion, posted memes and boasted heavily. | Deflected to other events in the war, seldom mentioned bridge. | Posted recruitment advertisements and made loose references to the explosion. |

| One-Year Anniversary of Invasion (24th February 2023) | Posted images of dead Russian soldiers, reposted Zelenskyy speech, and posted drone bombing footage. | Made solemn commemoration of the war, defended its legitimacy. | Posted dead Ukrainian soldiers and combat footage. |

Rhetorical Goals and Devices

In response to the first research question regarding the specific methods and rhetorical devices utilized on social media by Russian, Ukrainian, and Wagner forces, this study found that the most common themes between all sides were legitimization, deflection, humor, and violent content.

Legitimization

Figure 1. Post from Ukrainian Telegram channel “3-тя окрема штурмова бригада.” Text translates as: “Work at the headquarters on the front line near Bakhmut. Planning offensive actions of the 1st Assault Battalion.”

Images depict Ukrainian soldiers in a bunker surrounded by maps, papers, and computer screens.

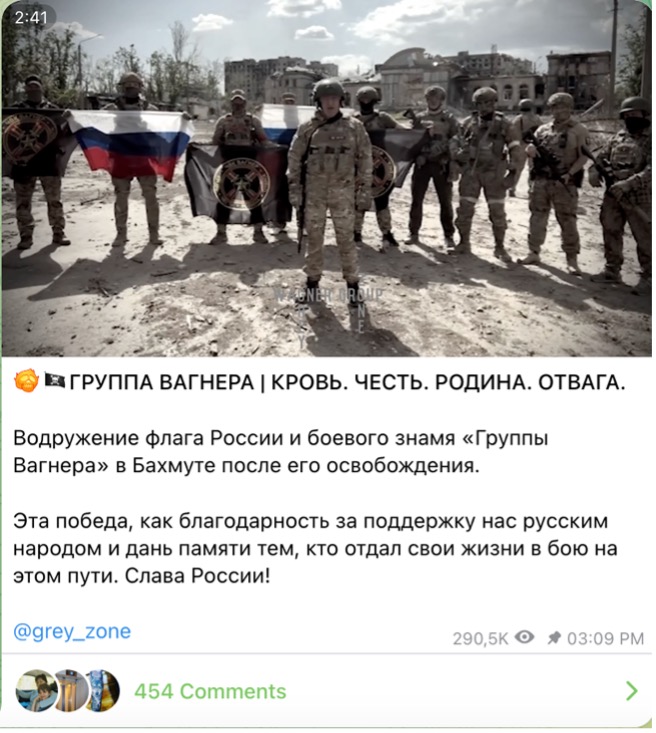

Figure 2. Post from Wagner Telegram channel “The Grey Zone.” Text translates as: “WAGNER GROUP | BLOOD. HONOR. HOMELAND. COURAGE. Raising the Russian flag and the battle banner of the Wagner Group in Bakhmut after its liberation. This victory is like gratitude for the support of the Russian people and a tribute to the memory of those who gave their lives in battle along this path. Glory to Russia!

Video depicts Yevgeny Prigozhin announcing the capture of Bakhmut.

In this usage, legitimization refers to a broad category of posts that are designed to bolster support for a particular force by flexing its military might, emphasizing a nation’s values, or utilizing examples of civilian support. One specific example of this comes from Ukrainian sources following the fall of Bakhmut. Bakhmut is an important strategic city located north of Donetsk in the Donetsk Oblast of occupied Ukraine. On May 20, 2023, Russian and Wagner forces captured the city after more than 200 days of street-to-street and building-to-building combat (Kullab & Litvinova, 2023). After the city fell, the Third Separate Assault Brigade of Ukraine posted a series of high-quality photos displaying soldiers hunched over maps and documents along with the caption “Work at the headquarters on the front line near Bakhmut. Planning offensive actions of the 1st Assault Battalion” (Figure 1). This post seeks to legitimize the war and battle by showing the front lines hard at work.

Russian forces also sought to use tactics of legitimization in the context of defeat. On October 8, 2022, Ukrainian forces utilized a remote weapons delivery system to partially destroy the Kerch Bridge, a Russian structure connecting Crimea to mainland Russia. This bridge is an important symbol for Russian nationalists because it symbolizes a tangible connection between Russia and Crimea, which was annexed by Russia in 2014. The destruction of the Kerch Bridge was hailed as both a symbolic victory and a significant infrastructural blow by Ukrainian forces. In the aftermath of the explosion, the pro-Russian Telegram channel Razved_Dozor posted a blurry video allegedly showing a Ukrainian civilian tearing down a Ukrainian flag in the city of Marhanets with the caption “In the city of Marganets (Dnepropetrovsk region), a citizen of Ukraine decided that the yellow-blue flag had an adverse effect on the residents of the city.” Instead of directly addressing the Kerch Bridge explosion, the Russian source immediately sought to legitimize Russian goals and delegitimize Ukrainian morale.

In the aftermath of the Battle of Bakhmut, Russian and Wagner sources relied heavily on legitimization to justify the long and casualty-heavy campaign. While the long-fought siege resulted in a Russian victory, it came at a significant cost in terms of funds, equipment, and manpower. One video that circulated through nearly every pro-Russian and pro-Wagner source was a video from May 20, 2023, showing Wagner leader Yevgeny Prigozhin announcing the capture of the city (Figure 2). In the video, Prigozhin salutes his fallen comrades and touts Russian propaganda while emphasizing the supremacy of Wagner’s capabilities. The Russian media mill generally lauded Wagner after the victory at Bakhmut, with the pro-Russian WarGonzo posting a video of Wagner soldiers posing with the Wagner flag flying over Bakhmut on May 20. This feverous embracement of Wagner after Bakhmut by Russian media sources may have ultimately been the final motivation for Prigozhin to launch his ill-fated “rebellion” against the Russian government just a month later.

The use of informational and accurate posts as a form of legitimization typically occurred only when the facts of a scenario served to benefit the force posting the content. One way that this phenomenon is manifested is in the form of posts from official government channels. After the Kerch Bridge explosion, the Ukrainian Deputy of the VRU Committee on National Security, Defense, and Intelligence, Yuriy Mysyagin, posted “another beautiful video” of the heavily damaged Kerch Bridge on his personal Telegram account. After the one-year anniversary of the invasion, a Telegram channel affiliated with the Ukrainian ZSU posted a video of Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy speaking to a G7 conference. These posts use Ukrainian public officials to legitimize the war effort, especially in the context of a perceived victory, such as at the Kerch Bridge.

A similarly official appeal to legitimization can be found in a Wagner recruitment post uploaded immediately following the Kerch Bridge explosion. Many Russian nationalists expressed displeasure that Russian security would allow such an attack, and Wagner sought to distance itself from the Russian army by emphasizing the force’s good pay and “the best special effects at concerts” for anyone who would join, even those who “have a criminal record or are on the blacklist.” This post is intriguing because it uses a Russian defeat to legitimize Wagner as a superior fighting force, rather than an allied force.

The final examples of legitimization on social media come in the form of long, text-based appeals to nationalist sentiment. This was seen prevalently in Russian channels following the one-year anniversary of the “special operation,” as the war raged on long past its intended end date. The Russian Razved_Dozor Telegram channel posted a letter emphasizing that “everything that happened in a year had to happen,” and that “We are our own people, Russia is our own civilization.” This post relies on emotional appeal and patriotic sentiment to spur legitimization, in a format that would be familiar to propagandists of old.

Deflection

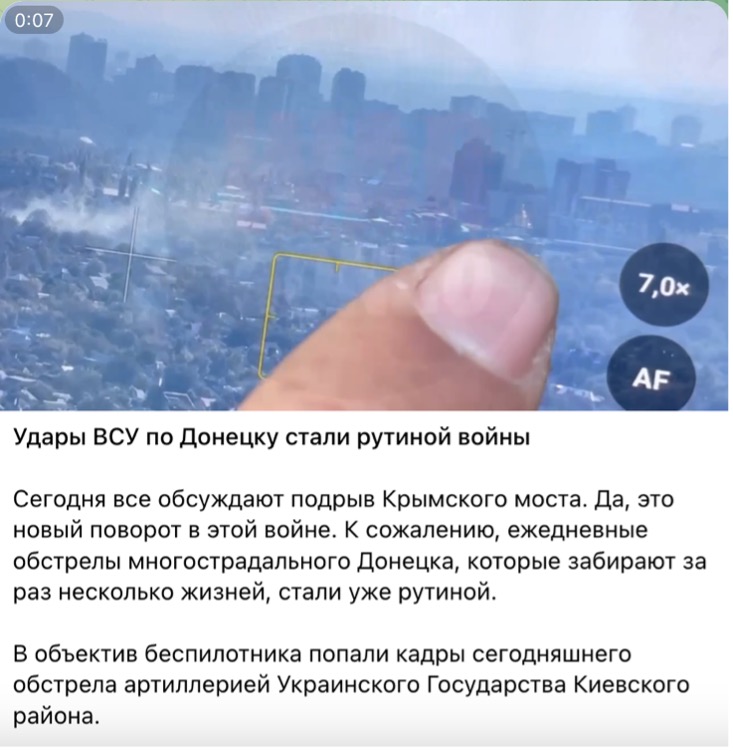

Figure 3. Post from Russian Telegram channel WarGonzo. Text translates as: “Today everyone is discussing the blowing up of the Crimean Bridge. Yes, this is a new twist in this war. Unfortunately, daily shelling of long-suffering Donetsk, which takes several lives at a time, has already become routine.”

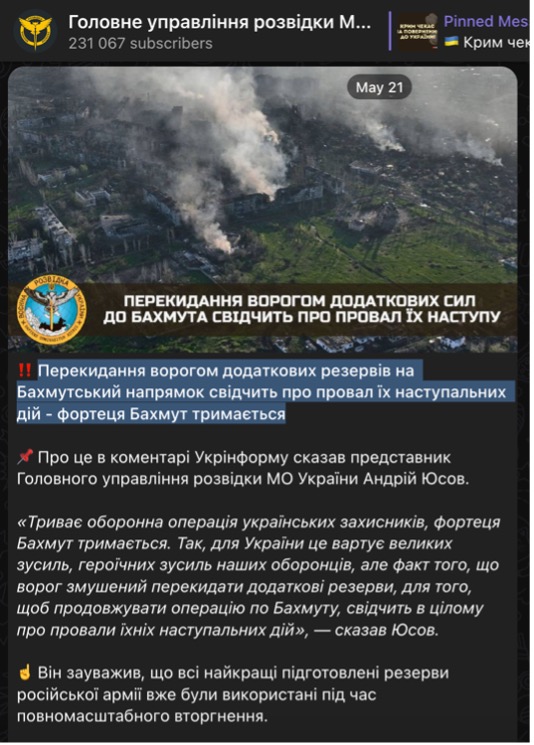

Figure 4. Post from Ukrainian Telegram channel “Головне управління розвідки МО України”. Text translates as: “The enemy’s transfer of additional reserves to the Bakhmut direction indicates the failure of their offensive actions – the Bakhmut fortress is holding.”

All three sources examined in this study engaged in the practice of deflection or misdirection. In this context, deflection concerns a source creating content that seeks to ignore negative results and emphasize some other event or talking point to downplay the significance of a perceived loss. In response to the Kerch Bridge explosion, Russian sources sought to deflect attention toward other issues. In a post from October 8 (Figure 3), the pro-Russian war correspondent channel known as WarGonzo posted a video showing a smoldering building with the caption “Today everyone is discussing the blowing up of the Crimean Bridge. Yes, this is a new twist in this war. Unfortunately, daily shelling of long-suffering Donetsk, which takes several lives at a time, has already become routine.” This post brushes over the attack on the bridge and emphasizes alleged war crimes occurring elsewhere in Russian-occupied Ukraine, therefore deflecting attention away from the explosion and minimizing its significance to the pro-Russian audience. Sources affiliated with the Wagner group also engaged in deflection in the wake of the Kerch Bridge explosion. On the day of the explosion, Wagner-affiliated Telegram channel The Grey Zone posted a long paragraph describing organizational changes that were occurring in the upper echelons of the Russian military structure. The post briefly mentions the explosion, but does not provide any detail in discussing the event.

Ukrainian sources also engaged in deflection. In a post from May 21, 2023, a Telegram channel belonging to the Main Directorate of Intelligence of the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine posted an image of burning buildings with the caption “The enemy’s transfer of additional reserves to the Bakhmut direction indicates the failure of their offensive actions – the Bakhmut fortress is holding” (Figure 4). This post came after the fall of Bakhmut was reported by the Associated Press and by Russia itself. However, despite this discrepancy, the Ukrainian source remained committed to emphasizing its allegedly strong hold on the city and the region. This post takes deflection to an extreme level.

Humor

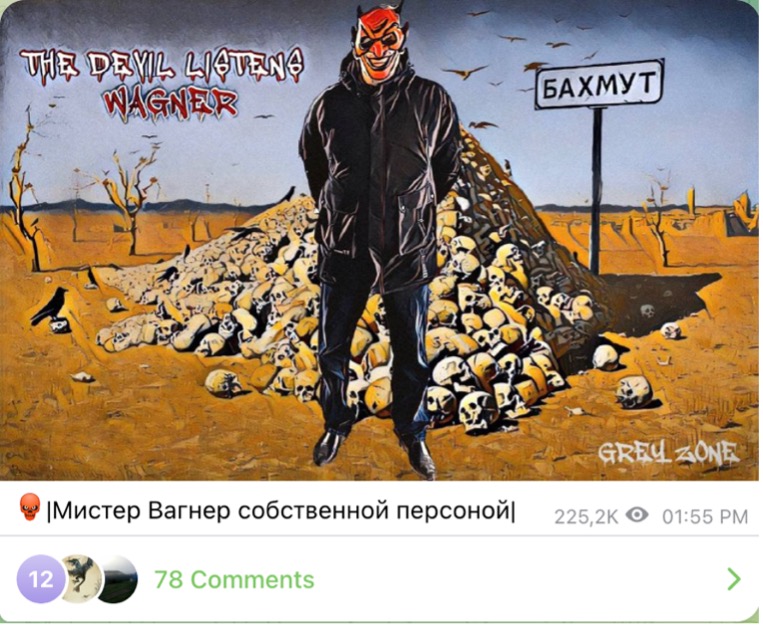

Figure 5. Post from Wagner Telegram channel “The Grey Zone.” Caption translates as “Mr. Wagner Himself.” Image depicts satanic figure standing in front of a pile of skulls next to a sign reading “Bakhmut.”

Figure 6. Post from Ukrainian Telegram channel “Оперативний ЗСУ.” No caption. Video depicts “Bongo Man” meme with burning Kerch Bridge in background.

Biały (2017) writes that “Visual content has two major functions – to impress or to dismay. It rarely has a purely informative character. It is also interesting to note the significant role played in psychological warfare by humoristic drawings and pictures.” (p. 85). Memes and humorous images or videos have long been a massive part of internet culture, so it should not be a surprise that civilians have taken to propagating memes to cope with the toll of the war. However, Russian and Ukrainian forces have also taken to posting such content. Due to the popularity of memes, integrating humorous images with traditional forms of propaganda has been a relatively fluid process for social media propagandists. Interestingly, official Russian channels do not seem as interested in posting humorous content as their Ukrainian and Wagner counterparts, but this requires more investigation.

The first category of humorous content found online represents images that are akin to traditional political cartoons. One example of this can be seen in a Wagner post following the fall of Bakhmut, where the victorious “Mr. Wagner himself” is portrayed as a horned devil standing over a pile of Ukrainian skulls (Figure 5). These posts are less about humor and more about using cartoons and hyperbolic imagery to transmit a message, in this case with the devil representing the lethal capability of Wagner mercenaries. The second category of humorous content, as alluded to earlier, takes the form of internet memes. Often, memes relating to the war attempt to capitalize on the meme trends of the current day. One example of this can be seen in the Ukrainian response to the Kerch Bridge explosion, when the official ZSU Telegram page posted a rendition of the briefly popular “bongo man” meme with the smoldering bridge in the background of the video (Figure 6).

Figure 7. Post from Ukrainian Telegram channel “СОКИРА UA” with caption translating “Wagnerites near Bakhmut.” Image shows rows of dead men.

Figure 8. Post from Wagner Telegram channel “The Grey Zone.” Image shows armed Wagner soldiers standing over the bodies of Ukrainian soldiers near Berkhovka.

One recent phenomenon is the act of posting violent content online. This trend was pioneered by fighters of the Islamic State, who gained notoriety for posting videos of beheadings and bombings on their media feeds, striking fear into the hearts of civilians and opposing soldiers the world over. Official channels tend to shy away from posting content directly showing death, but in a war with so many third-party content aggregators and semi-detached units, large amounts of violent content have emerged online and become some of the most popular videos of the war, likely due to their shock value and prevalence as propaganda tools. Every side engages in posting violent content, but this study found that Wagner and individual Ukrainian unit channels were much more likely to do so.

Around the one-year anniversary of the invasion, a Telegram channel branding itself as the “Ax of the UA (Ukrainian Army)” posted an image of dozens of partially dressed dead soldiers with the caption “Wagnerites near Bakhmut” (Figure 7). At the same time, Wagner channel The Grey Zone posted two images of dead Ukrainian soldiers near Berkhovka and a video of a skirmish near Vugledar, both located along the front lines in the occupied Donetsk Oblast where most of the fighting has occurred for the duration of the war (Figure 8). The motivation for posting these videos appears to be very similar to the motivation for posting legitimizing content; that being a desire to emphasize one force’s military might while portraying the opposing side as weak or ineffectual.

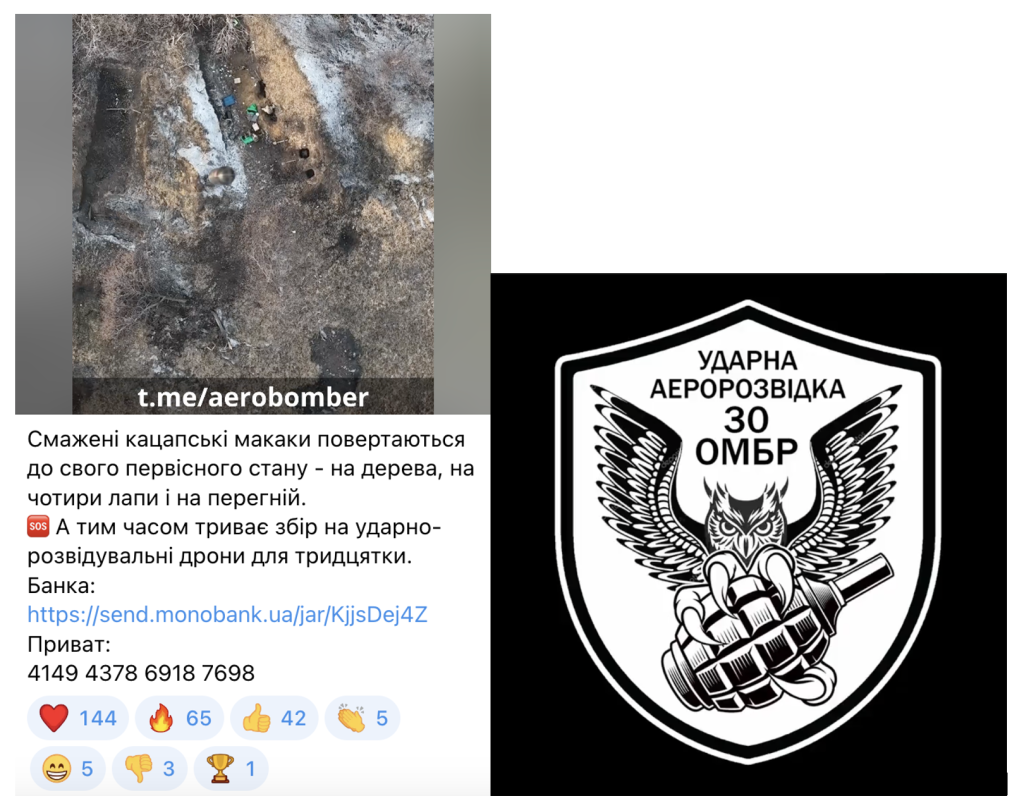

Figures 9 and 10. Post from Ukrainian Telegram channel “Aerobomber,” allegedly tied to the Strike Aerial Reconnaissance 30th OMBR unit. The image on the left shows an image from a drone’s video camera as a grenade falls on a group of Russian soldiers. The image on the right is the unit’s self-designed insignia, depicting an owl clutching a grenade in its talons.

During the war, modified civilian drones have been used, primarily by Ukrainian forces, to deliver explosive payloads, usually in the form of a grenade or small bomb. Because many of these drones come with cameras, recordings of these deadly attacks are some of the most common and intimidating videos on the internet. The message from Ukrainian posters is clear: death can come from above at any time, and Russian soldiers probably won’t hear it until it is too late. The format of these videos is almost universal: a heavily watermarked video with hardbass-style music blaring in the background shows a drone’s point of view as it hovers above a group of soldiers before ultimately dropping the payload, leading to an explosion and the often slow, painful deaths of the enemy. Entire units of the Ukrainian Army, such as the Strike Aerial Reconnaissance 30th OMBR, are dedicated to drone warfare, and have become prolific in their posting habits (Figures 9 and 10). The logo for the 30th OMBR is an Owl holding a grenade in its talons, with the pin already pulled.

Similarities and Differences Between Sides

The second research question that this study sought to analyze was the similarities and differences among Russian, Ukrainian, and Wagner posting patterns. One commonality between official Russian and Ukrainian channels was their reliance on content aimed at legitimizing the war effort. These videos and images are perhaps the most palatable and “appropriate” form of social media propaganda. The content is largely aimed at soliciting support, and therefore maintains an authoritative tone. All three sides similarly engaged in deflective tactics to maintain a morally superior tone while ignoring or minimizing losses and negative facts. Ukrainian- and Wagner-affiliated sources were more likely to engage in posting violent content and drone bombing videos than their Russian counterparts, but individual pro-Russian content aggregators were willing to do so. Finally, meme content was spread throughout all three sources, but Ukrainian- and Wagner-affiliated sources were again more willing to participate in this trend. Ultimately, it appears that Ukrainian- and Wagner-affiliated channels were more likely to post edgier and more violent content, while Russian sources attempted to maintain a balanced and authoritative tone.

Potential Benefits

Regarding the third research question, the perceived benefits of these different types of content varies. The case for legitimization appears to be straightforward. By emphasizing one’s strengths and the enemy’s weaknesses, propagandists seek to win hearts and minds for the cause. The invasion of Ukraine has resulted in mass conscription in both Ukraine and Russia, and as a result the popularity of the war has been in flux for both sides. According to a Gallup poll from October 2023, the popularity of the war has decreased among Ukrainians from 70% to 60% in the past year (Vigers 2023). The popularity of the war among Russian civilians fell by a very similar 9% in almost the same period (Pribylov 2023). In the examples reviewed by this study, legitimization ranged from images displaying military might to long letters conveying patriotic passion. One video allegedly depicting a Ukrainian civilian tearing down a Ukrainian flag displays the heart of the issue – Russian and Ukrainian propagandists believe that legitimization helps bolster civilian morale and to give credence to their actions.

Deflection serves as the opposite of legitimization in its purpose. By deflecting attention away from losses to other issues, militaries seek to maintain their image of superiority and strength through silence. This can come in the form of either briefly acknowledging or flatly ignoring a negative fact, which is consistent with propagandist techniques from the past. Ukraine and Russia are far from the only nations to engage in this activity during war or peace, but it has become an enshrined tactic in the current war.

Humorous videos and images, along with internet memes, may serve to raise the spirits of the civilians and soldiers consuming content. Morale is a highly important resource in warfare, and the depletion of morale is tantamount to defeat itself in many scenarios. Therefore, the usage of memes as online propaganda can be interpreted as an attempt to win a war on the mental front. Furthermore, memes spread quickly across the internet due to their replicability and popularity, so integrating propaganda into memes is a good way of ensuring that a message spreads to a desired audience. This tactic has been used heavily by political campaigns in America to increase awareness, and it is likely that memes play a similar role in the Russo-Ukrainian War.

Violent content and drone bombing videos are a relatively new phenomenon in hybrid warfare. The initial impulse is to label these videos as an attempt to shock and demoralize the enemy through violent and jarring videos of their countrymen’s deaths. However, the presence of quick techno music and a flashy editing style implies that these videos may serve the primary purpose of energizing and exciting Ukrainian civilians and soldiers. More research is necessary to determine the exact motivation for this style of content, but its prevalence is certainly significant and noteworthy.

V. Discussion

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the prevalence of social media propaganda in the Russo-Ukrainian War is how it reaches and interacts with Western audiences. Online communities, such as Reddit’s r/NonCredibleDefense or r/CombatFootage, are dedicated to posting and compiling large quantities of footage and memes from all sides of the war, often with shaded intent. Accounts such as Instagram’s atlas.news3 or ourwarstoday2 appear to be genuinely journalistic in their efforts, and post content from a wide range of topics including the Russo-Ukrainian War. However, individual accounts on Reddit posting to r/NonCredibleDefense may be posting content simply because it is shocking and will generate large amounts of discussion and “upvotes.” The most viewed and upvoted content on combat-focused subreddits is consistently content that shows close-quarters combat, impressive aerial duels, or simply the biggest explosions. Western, English-speaking audiences on these platforms appear to be overwhelmingly pro-Ukraine, but not universally so. Many commenters appear to be there simply for the spectacle, but in an age where irony and apathy are dominant, it is difficult to obtain a genuine perspective on these consumers based on their online comments and interactions.

The ultimate question of the hybrid warfare effort from both sides is whether their efforts are successful in turning the hearts and minds of domestic and foreign civilians and soldiers. This study has documented the rhetorical goals and devices employed by Russian, Ukrainian, and Wagner forces on social media, but the actual impact of these posts is unclear. Early in the war, reports surfaced of Russian soldiers surrendering en masse to Ukrainian soldiers and civilians alike, allegedly influenced by part in seeing their countrymen die on social media. However, today these reports are absent from major media cycles in the west. With no end to the war in sight, the continued efforts of social media propagandists increasingly resemble the trench warfare that the conventional soldiers of Russia and Ukraine are mired down in. Finally, this research was limited by several factors that warrant evaluation in future research. The form factor of this research inherently limited its sample size, the scope of the research questions was ambitious, and the findings of the research were widely reliant upon the services of Google Translate as opposed to a more robust translating approach.

VI. Conclusion

The ongoing phase of the Russo-Ukrainian War has led to an escalation in the amount and intensity of social media posting from channels associated with Russian, Ukrainian, and Wagner forces. This study examined the rhetorical goals and devices employed by these channels and found that the four primary goals of social media content were to legitimize, deflect, humorize, or convey violent content. This research further found that the posting patterns between all sides of the social media battle were relatively consistent across sides, but that Russian sources often deferred to post as much violent content as their Ukrainian or Wagner-associated counterparts. Finally, this research offered qualitative interpretations of the perceived benefits of each type of rhetorical goal, all ultimately attempting to either bolster or dishearten the morale of civilians and soldiers.

This research has only skimmed the surface concerning rhetorical goals and devices in hybrid warfare. The sheer amount of content not examined by this study demonstrates the need for more research focused on better categorizing social media posts. Additionally, research must be conducted to ascertain the internal motivations for such posting. However, without internal documents or whistleblowers, this data will be difficult to obtain. Similarly, more research must be done to determine the ways in which social media propagandists selectively target either pro-Russian or pro-Ukrainian consumers.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank Dr. Daniel Haygood, whose mentorship and guidance was instrumental to the completion of this project. I also want to thank Dr. Michael Carignan for nurturing my interest in research and higher learning. Finally, I thank my friends and family for their unwavering support throughout the process of writing and presenting this research.

References

3-тя окрема штурмова бригада [@ab3army]. (2023, May 25). Робота у штабі на передовій під Бахмутом. Планування наступальних дій 1-го штурмового батальйону. [Images]. Telegram. https://t.me/ab3army/2594

Biały, B. (2017). Social media—From social exchange to battlefield. The Cyber Defense Review, 2(2), 69–90. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26267344

Brown, J. (2018). An alternative war: The development, impact, and legality of hybrid warfare conducted by the nation state. Journal of Global Faultlines, 5(1–2), 58–82. https://doi.org/10.13169/jglobfaul.5.1-2.0058

СОКИРА UA. (2023, February 22). Вагнеровцы под Бахмутом. [Image]. Telegram. https://t.me/c/1663363761/7871

Danyk, Y., & Briggs, C. M. (2023). Modern cognitive operations and hybrid warfare. Journal of Strategic Security, 16(1), 35–50. https://doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.16.1.2032

Feezell, J. T. (2018). Agenda Setting through social media: The importance of incidental news exposure and social filtering in the digital era. Political Research Quarterly, 71(2), 482–494. http://doi.org/10.1177/1065912917744895

Головне управління розвідки МО України [@DIUkraine]. (2023, 21 May). Перекидання ворогом додаткових резервів на Бахмутський напрямок свідчить про провал їх наступальних дій – фортеця Бахмут тримається Про це в коментарі. [Image]. Telegram. https://t.me/DIUkraine/2333

Grey Zone [@grey_zone]. (2022, October 8). В «Группе Вагнера» снова смотр новоявленных музыкантов для гастролей за рубежом! • достойное финансовое вознаграждение (сколько и обещано, в отличии от. [Image]. Telegram. https://t.me/grey_zone/15260

Grey Zone [@grey_zone]. (2022, October 8). В связи с осуществлённой атакой Украины на «Крымский мост», сместились планируемые и уже несколько недель проводимые перестановки в Министерстве обороны. [Text]. Telegram. https://t.me/grey_zone/15262

Grey Zone [@grey_zone]. (2023, February 24). Подтверждающие кадры из Берховки, которая сегодня утром перешла под контроль ЧВК «Вагнер» В результате тяжелых боев противник не выдержал натиска. [Image]. Telgram. https://t.me/grey_zone/17380

Grey Zone [@grey_zone]. (2023, February 24). Кадры из под Угледара, где бойцы бригады морской пехоты Тихоокеанского флота России штурмовали укрепрайон противника. В одном из эпизодов боя. [Video]. Telegram. https://t.me/grey_zone/17386

Grey Zone [@grey_zone]. (2023, May 20). |Мистер Вагнер собственной персоной|. [Image]. Telegram. https://t.me/grey_zone/18706

Grey Zone [@grey_zone]. (2023, May 20). ГРУППА ВАГНЕРА | КРОВЬ. ЧЕСТЬ. РОДИНА. ОТВАГА. Водружение флага России и боевого знамя «Группы Вагнера» в Бахмуте после его освобождения. Эта. [Video]. Telegram. https://t.me/grey_zone/18709

Hanlon, B. (2018). It’s not just Facebook: Countering Russia’s social media offensive. German Marshall Fund of the United States. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep18880

Kullab, S., & Litvinova, D. (2023, May 23). Russia TV celebrates as it reports the capture of Bakhmut, comparing it to Berlin in 1945. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-bakhmut-79ce2a44951613509ce9d1afede86f97

Lin, H. (2022). Russian cyber operations in the invasion of Ukraine. The Cyber Defense Review, 7(4), 31–46. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48703290

Mullaney, S. (2022). Everything flows: Russian information warfare forms and tactics in Ukraine and the US between 2014 and 2020. The Cyber Defense Review, 7(4), 193–212. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48703300

МИСЯГІН [@mysiagin]. (2022, October 8). Пропагандисти показали ще прекрасне відео того, як виглядає Кримський міст. На жаль, одна смуга вціліла – але пропускають лише легкові автомобілі. [Videos]. Telegram. https://t.me/mysiagin/15193

Оперативний ЗСУ [@operativno]. (2022, October 8). [Video]. Telegram. https://t.me/operativnoZSU/47065

Оперативний ЗСУ [@operativnoZSU]. (2023, February 24). Володимир Зеленський: Взяв участь у зустрічі лідерів «Групи семи». Наша зустріч мала дві частини. У першій, публічній частині подякував партнерам. [Video]. Telegram. https://t.me/operativnoZSU/80654

Pribylov, S. (2023, September 6). Russia’s shifting public opinion on the war in Ukraine. Voice of America. Retrieved from https://www.voanews.com/a/russia-s-shifting-public-opinion-on-the-war-in-ukraine-/7255792.html#:~:text=As%20a%20result%2C%20researchers%20estimate,convinced%20supporters%20of%20the%20war

Prier, J. (2017). Commanding the trend: Social media as information warfare. Strategic Studies Quarterly, 11(4), 50–85. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26271634

Ratsiborynska, V. (2016). When hybrid warfare supports ideology: Russia Today. NATO Defense College. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep10246

Razved Dozor [@Razved_Dozor]. (2022, October 8). В г. Марганец (Днепропетровская обл.) гражданин Украины решил, что желто-синий флаг неблагоприятно влияет на жителей города. [Video]. Telegram. https://t.me/razved_dozor/2424

Razved Dozor [@Razved_Dozor]. (2023, February 24). Друзья Пожалуй, многие, как и я, смотрели обращение президента. Задумалась. Все, что произошло за год должно было произойти. Россия должна [Image]. Telegram. https://t.me/razved_dozor/3810

Razved Dozor [@Razved_Dozor]. (2023, May 20). Бахмут (Артёмовск) взят! 20.05.2023 сегодня по полудню был полностью взят Бахмут Заявление Пригожина о взятии населенного пункта Бахмут силами ЧВК «Вагнер». [Video]. Telegram. https://t.me/razved_dozor/4279

Rosenberry, J., & Vicker, L. A. (2021). Applied mass communication theory (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis.

Ross, R. J., & Rutland, J. (2022). A military of influencers: The U.S. Army social media, and winning narrative conflicts. The Cyber Defense Review, 7(4), 213–226. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48703301

Ударна аеророзвідка 30-ОМБР [@aerobomber]. (2023, February 24). Смажені кацапські макаки повертаються до свого первісного стану – на дерева, на чотири лапи і на перегній. А тим часом триває. [Video]. Telegram. https://t.me/aerobomber/25

Vigers, B. (2023, October 25). Ukrainians stand behind war effort despite some fatigue. Gallup.com. Retrieved from https://news.gallup.com/poll/512258/ukrainians-stand-behind-war-effort-despite-fatigue.aspx#:~:text=%25%20Ukraine%20should%20continue%20fighting%20until%20it%20wins%20the%20war&text=Ukrainians’%20views%20that%20their%20country,72%25%20in%20the%20Northern%20region

WarGonzo [@WarGonzo]. (2022, October 12). Удары ВСУ по Донецку стали рутиной войны Сегодня все обсуждают подрыв Крымского моста. Да, это новый поворот в этой войне [Video]. Telegram. https://t.me/wargonzo/8647

WarGonzo [@WarGonzo]. (2023, February 24). Проекту «Трибунал» — год! Мы находим и публикуем информацию о преступлениях и пытках нацистов из «Азова» и ВСУ в отношении мирных [Video]. Telegram. https://t.me/wargonzo/11091

WarGonzo [@WarGonzo]. (2023, May 20). Флаг над Артёмовском/Бахмутом. [Video]. Telegram. https://t.me/wargonzo/12651