- Home

- Academics

- Communications

- The Elon Journal

- Full Archive

- Fall 2024

- Fall 2024: Claire Kenealy

Fall 2024: Claire Kenealy

Climate Change Communication: How Young Social Media Users Respond to Positive and Negative Messaging

Claire Kenealy

Strategic Communications, Elon University

Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements in an undergraduate senior capstone course in communications

Abstract

Communicating effectively about climate change is a key to saving the planet. Climate change is often perceived as distant and daunting, but improved communication has the potential to create positive change by engaging and empowering young people. Social media is a leading source for news information and is an ideal place to reach this audience. This research aimed to determine how Environmental NGOs can best use social media to effectively communicate with young audiences, specifically differentiating between optimistic and pessimistic climate change communication. During two focus groups, Elon University students discussed their previous experience with climate change communication, brainstormed content that they could see themselves being engaged by and responded to optimistic and pessimistic social media posts from Sierra Club and Greenpeace. Participants assigned a numeric level of empowerment and an emotion to each post. Overall, roughly 70% of the most empowering posts were pessimistic. Participants expressed an appreciation for personal appeal, specificity, and calls to action. This study indicates that pessimistic content regarding climate change cannot be abandoned but must be strategically created. Climate change communications content should establish a fear- inducing problem that directly relates to its intended audience and provide a specific and accessible call to action.

Keywords: climate change, communication, social media, focus groups

Email: ckenealy@elon.edu

I. Introduction

Communicating effectively about climate change is a key to saving the planet. Despite expressing concern about climate change, the American public does not follow climate change news closely (Skurka et al., 2022). Furthermore, many people see climate change as distant because it is not always visible (Hibberd & Nguyen, 2013). This indicates the failure of communicators to engage audiences in the issue.

Social media is a leading source for news and information (Kim et al., 2024). Social media has the potential to serve as a tool for engaging and empowering young audiences, whom the burden of climate change will fall upon. Environmental NGOs (eNGOs) use social media, but few have large online audiences (Kim et al., 2024). Pessimistic and optimistic approaches to climate communication have both been used in climate change communications. Pessimistic climate change communications often use threat appeals which attempt to motivate people to act by evoking fear. This communication style encourages avoidant or protective action (Skurka et al., 2022). In contrast, optimistic climate change communications is more solution-oriented and uses hope to encourage action (Hawley & Mocatta, 2022). This research aims to determine how eNGOs can best use social media to effectively communicate with young audiences, specifically differentiating between optimistic and pessimistic climate change communication.

II. Literature Review

Current literature regarding climate change communications identifies faults and specific strategies for improvement. The literature explores the significance of emotions in communicating effectively on the issue and evaluates young peoples’ response to the media. This literature review focuses on these areas with an appreciation for how the scholarly conversations impact one another.

Scholarly literature suggests that climate communication that effectively informs does not always translate to engagement. The information deficit model proposes that the public’s lack of engagement on the issue of climate change is due to a lack of knowledge on the issue. This model has been deemed inadequate as a communication strategy and it has been suggested that individuals’ ideologies rather than climate literacy levels determine their engagement in the issue. A study of young people in the United Kingdom (UK) corroborates this point, as it found that many young people were informed about climate change yet were not actively engaging in the issue (Hibberd & Nguyen, 2013). When climate change is only taught as it relates to science, the issue maintains a distance from the concept of the self and remains abstract. People tend to place the impacts of climate change at a psychological distance. According to research by Lee and Barnett, “education strategies that frame the threat of climate change as more local and personally relevant, rather than focusing on the abstract and distant, may be helpful in reducing psychological distance” (Lee & Barnett, 2022). Furthermore, emotional effects caused by climate communication caused 50% of variance in support of climate policies (Hawley & Mocatta, 2022). However, when given the option between funny, scary, or informational content, over one in three participants in a study chose informational content (Skurka et al., 2022). This suggests that informative content still has the potential to engage audiences and should not be abandoned altogether.

Research suggests that personal and localized storytelling is an effective way to increase engagement in climate issues because it is more relatable and comprehensible than stories about global threats (Hawley & Mocatta, 2022). Furthermore, “research shows that people are more influenced by direct experience and immediate demands rather than vicarious experiences or abstract data” (Shelter, 2021). Broad “awareness” stories have drowned out news about specific climate events of the Global South (Ejaz & Najam, 2023). Research suggests that these specific stories will lead to more engagement. Young people in the UK perceive a lack of relevance of climate change to their daily lives. Specifically, “many members felt that too often the media did little to represent them, to link climate change to their own interests and concerns, or to offer them practical day-to-day solutions” so scholars suggest that communicators “bring the earth to the backyard” (Hibberd & Nguyen, 2013). This argument is corroborated by researchers who conducted interviews with representatives of institutions that supported scientific consensus on climate change, had at least 1,000 followers on Twitter, and primarily posted about climate change or environmental issues. Their findings indicate that finding common ground, emphasizing the here and now, focusing on the benefits of engagement, and creatively empowering people are essential themes when generating effective content about climate change (León et al., 2023). This research indicates that storytelling that targets specific audiences is essential to crafting empowering climate communication.

Climate change communication often lacks awareness of the diversity of audiences. Climate communication has been driven by the international climate institutions of the Global North, excluding the perspectives of the Global South. The Global North consists of highly industrialized nations while the Global South consists of less industrialized nations. Climate scholars of the Global North tend to focus on the commonality of the issue of climate change. This is problematic because all countries have contributed different amounts to the issue, will be impacted differently by the issue, and have varying ability to respond to the issue (Ejaz & Najam, 2023). Researchers who conducted a focus group in the UK found that a primary reason for climate communication’s failure to engage is its disregard for audience diversity (Hibberd & Nguyen, 2013). Whether referring to socioeconomic diversity within a country or more fundamental differences on a regional scale, well-rounded and targeted communication is essential.

Another issue with climate communication is that despite the growing trend in the amount of climate change coverage in the media worldwide, it consistently peaks at certain moments such as Earth Day and upon the release of climate reports (Ejaz and Najam, 2023). Young people in the UK believe that there is not enough media coverage of climate change for it to be that important. One focus group participant even said that it seemed like “filler” material when it was included in the news (Hibberd & Nguyen, 2013). Climate-coverage in the news media dropping following January 2020 when COVID-19 pandemic coverage became prioritized is one example of the issue being neglected. Furthermore, “temporally and spatially distant climate impacts are easily overshadowed by immediate physical needs, professional demands, economic necessities, and social obligations” (Shelter, 2021). As the past scholarship suggests, that climate change communication must be consistent and engaging to receive attention.

In a high-choice media environment, humor is indicated to have the most potential to grab people’s attention. In one study, more participants in a study selected funny videos than scary or informational ones. Conservatives and women both preferred the funny and scary video to the informational video. Conservatives’ preference for the funny video reflects the role of humor as a gateway communication strategy, meaning that people who lack interest or belief in an issue are more likely to engage with humorous content (Skurka et al., 2022). Other research by the scholars referenced concluded that watching humorous videos increased perceived risk for those aged 21.9 and younger but decreased perceived risk for those 26.3 and older (Skurka et al., 2022). The humor appeal serves as an alternative that has been deemed effective only on young audiences.

There is an ongoing discussion among scholars regarding optimistic climate communication. The lack of positive and relevant messages in climate change communication has led to disengagement among young people in the United Kingdom. Scholars suggest that climate change communication needs to stop focusing on the extreme and controversial because it is leading to a paralyzing sense of pessimism and hopelessness. This emphasis on pessimistic communication that evokes fear may be called “scaremongering” and it has been guilty of disengaging and antagonizing young people (Hibberd & Nguyen, 2013). Pure fear-based messaging in climate change communication has been ineffective in increasing engagement. Mood management theory suggests that people are motivated to optimize their moods and studies indicate that threatening portrayals of climate change have been and will likely be avoided because they evoke unwanted feelings of anxiety (Skurka et al., 2022). Damon Gameau, director of a climate change documentary titled 2040, argues, “It’s all well and good to sound the fire alarm, that’s really important, but if you don’t show people where the exits are, then you’re going to get paralysis, and people are going to freeze and not know what to do. And I think that’s all we’ve been doing – sounding the fire alarm” (Hawley & Mocatta, 2022). Scholars analyzed the fact-based dreaming approach of Gameau’s documentary and proposed this approach as a strong alternative to scaremongering or absolute optimism.

Fact-based dreaming is defined as “a process which involves mobilizing the creative power of imagination to subvert established thought patterns while anchoring such imagination in present-time reality” (Hawley & Mocatta, 2022). Scholars assert that it “is most productive when it incorporates the voices, imaginings and perspectives of children and young people.” A film like 2040 risks promoting “toxic positivity” that is a barrier to creating climate change engagement, but the positivity of this film is arguably used as a tool for empowerment rather than mere consolation. Scholars assert that fact-based dreaming is solution-oriented; it informs on the horrors while providing a roadmap of realistic hope (Hawley & Mocatta, 2022). This previous scholarly literature suggests that optimistic and pessimistic climate communication cannot empower independently; they must be tactfully balanced and interwoven.

Scholars predict that climate reporting will be forced to shift from explaining why climate change is important and providing general solutions to reporting on the real-time climate impacts as climate disasters strike more often. Poorer and less industrialized countries are most vulnerable to climate disasters, so the current flow of climate change communication will be flipped, and wealthier countries will be forced to consume narratives coming out of these low-emissions countries. Climate change coverage will inevitably become more nuanced because it will be forced to become less conceptual and more specific as climate disasters play-out. The 2022 floods in Pakistan led to a Pakistani framing of the issue across global media that focused on the human impacts of the events. Pakistan became the “maker” of global news regarding climate change in this instance. A continued shift in this direction will make global climate change communication more complex and accurate and less abstract (Ejaz & Najam, 2023).

However, “as the threats of climate change become increasingly close, people may no longer view the topic as appropriate fodder for comedy, maybe leading to message discounting” (Skurka et al., 2022). Therefore, this evolution in communication focus is relevant to the discussion about optimism and humor. It is also important to note that a study found that both threat and humor appeals in videos that were effective in promoting young adults’ engagement in climate activism in 2016 were not effective in 2020 (Skurka et al., 2022). As the issue worsens, empowerment through climate communication is likely to grow more difficult, making continued research essential.

III. Methods

This study adds to the scholarly conversation regarding effective climate change communication by asking the questions:

RQ1: How do younger audiences respond to optimistic versus pessimistic messaging in social media regarding climate change?

RQ2: How do younger audiences respond to other characteristics typical of climate change communication via social media?

Previous literature has analyzed current climate communication and the impact of emotional appeals but has yet to reach a consensus on the most effective messaging strategy. This study focuses specifically on American college students’ reactions to climate change messaging on social media to add a new demographic and current perspective to the ongoing conversation.

This study uses a focus group methodology. Just like Lee and Barnett’s focus group study exploring adolescents’ representations of climate change, this study recruited groups of four or five participants. Due to time constraints, this study consisted of two focus groups rather than five. Participants were students at Elon University and selected from numerous areas of study to ensure that various perspectives are represented. One focus group in this study consisted of an Environmental Science major, a Strategic Communications and Media Analytics double major, a Journalism major, a Cinema and Television Arts major, and an Elementary Education major. Another focus group consisted of a Political Science and Psychology double major, an Economics and Music Production double major, a Biochemistry major, and an Economics major.

Familiarity within members of focus groups has the potential to generate more natural, elaborate, and complex data (Lee & Barnett, 2022). Therefore, the study did not avoid including participants that knew one another. Just like Lee and Barnett’s study, this study informed participants of the general topic of discussion and emphasized that there were no right or wrong answers. Participants signed a release form that outlined the study and provided their consent to participate and be audio recorded.

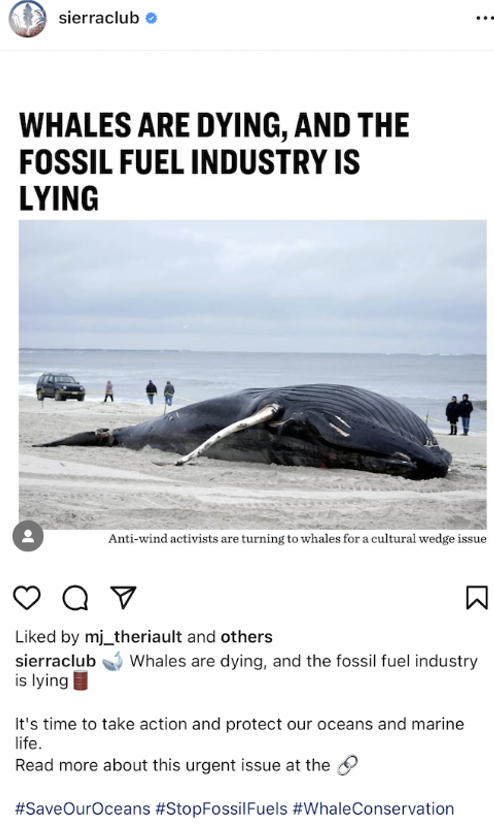

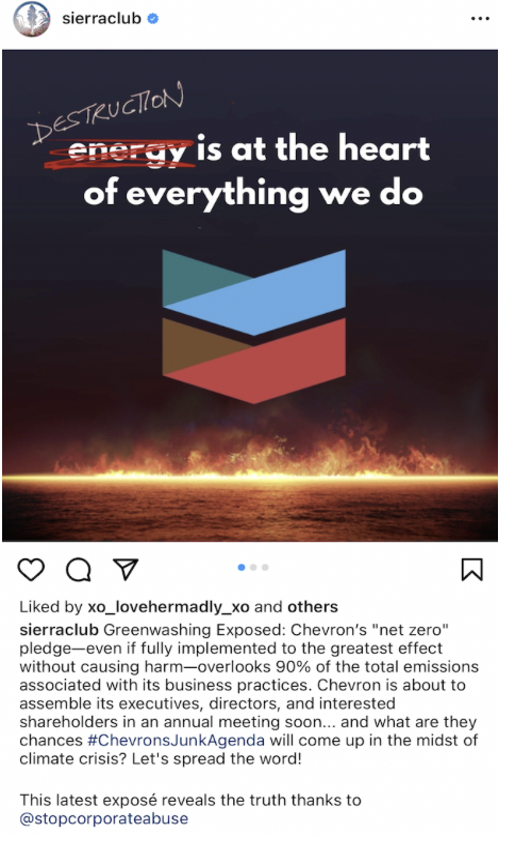

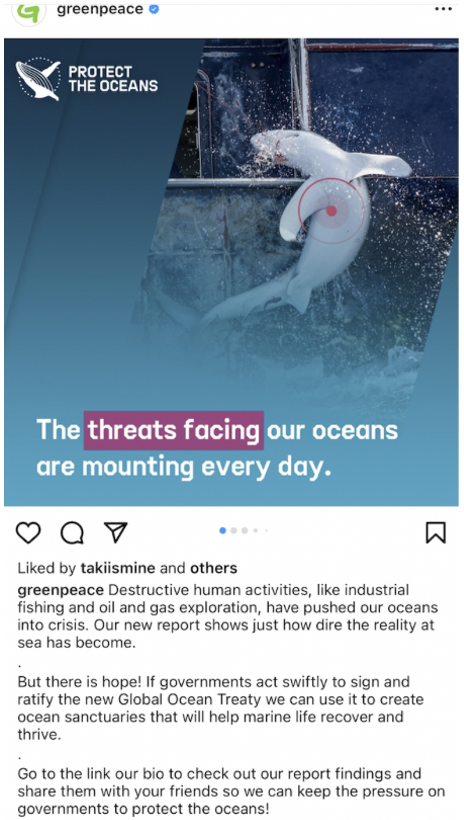

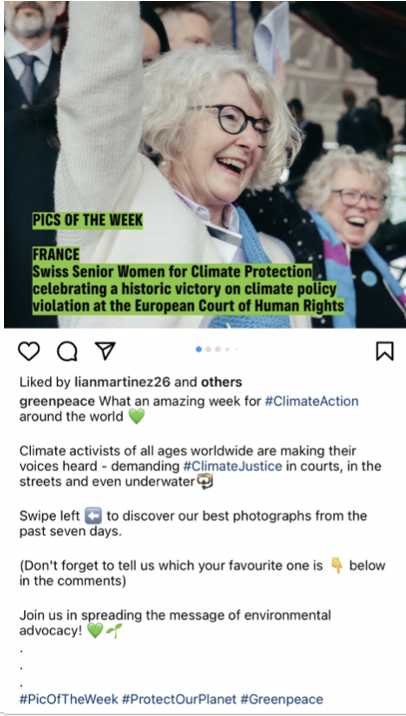

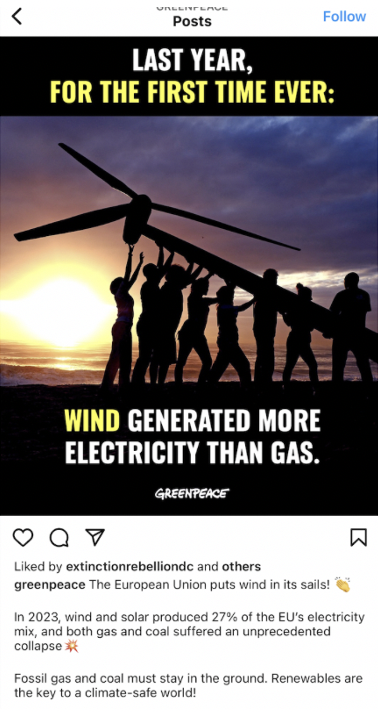

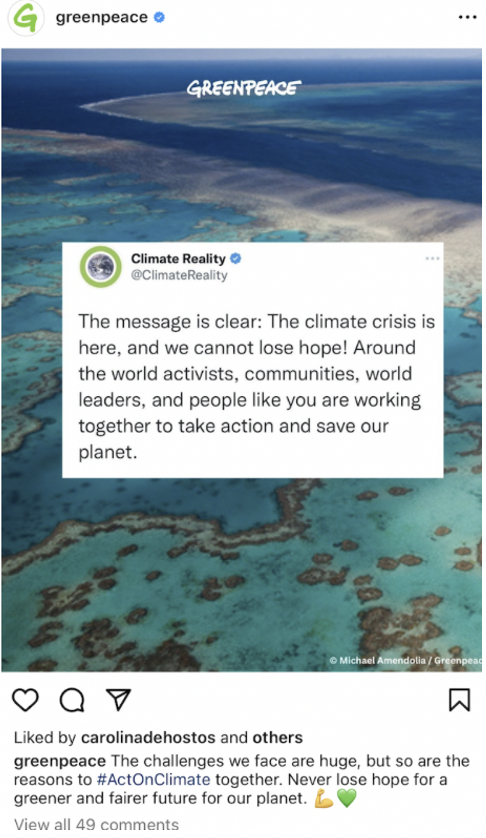

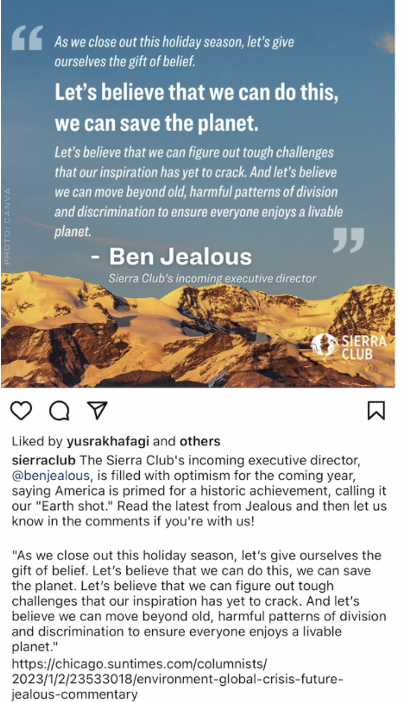

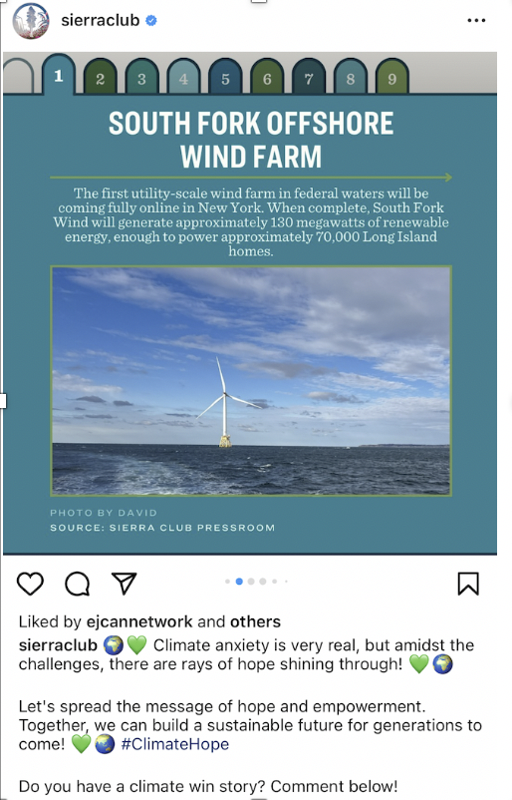

Each focus group began with a five-minute discussion about members’ experience with climate change communication. Then, they were exposed to a series of 10 social media posts from Greenpeace and Sierra Club, two organizations among the eNGOs with the largest average social media follower counts (Kim et al., 2024). Half of these posts were categorized as pessimistic and feature images of the horrors of climate change or intimidating language. Half of these posts were categorized as optimistic and feature hopeful calls to action and highlights of environmental activism success stories. The criteria used to select optimistic posts was that the post’s primary focus was on hope for the future. This included posts about technology, policies, and strategies that have the potential to help the planet. The criteria used to select pessimistic posts was that the post’s primary focus was on either environmental devastation of the past or threatening projections of the future. This included posts about events like natural disasters and melting icebergs as well as fear-evoking information regarding the way that the planet’s health is currently tracking. Negative posts portrayed the future that will come if society does not act on climate change while positive posts portrayed the ways that society can act. These posts were randomly ordered, with pessimistic and optimistic posts being interwoven. This study could be repeated with varying posts, so long as they meet the general descriptions of the categories explained. However, the specific posts used are provided in the Appendix should a future researcher wish to replicate this study.

Participants each had a sheet of paper with sections numbered one through ten. Each section had the questions: In one word, how does this make you feel? On a scale of one through ten, how likely are you to increase your involvement in solving the issue of climate change after seeing this? Participants were given thirty seconds to make note of their immediate reactions. After seeing all the posts, participants discussed their answers with one another and explained their logic for fifteen minutes. The focus group concluded with a fifteen-minute discussion about the content they personally could see themselves being engaged and empowered by; this portion of the conversation was a place for idea generation and creative brainstorming.

The focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed. This study used an inductive content analysis approach of the transcripts, meaning that specific instances were observed and then combined into general statements (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). The data was coded, the codes were grouped, and themes were identified. This approach was selected because the research aims to generate new ideas rather than test pre-existing theories (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). Respect for persons, beneficence, and justice guided this study (Sims, 2010). Participation was consensual, anonymity was guaranteed, and the focus group leader created a safe environment for discussion. This study was reviewed by Elon’s Institutional Review Board before interviews began and deemed exempt.

IV. Results

Participants engaged in open dialogue and built upon one another’s ideas. Participants gravitated towards the discussion of certain themes which generated the following results.

Current Climate Change Communication

Participants were unimpressed by current climate change communication on social media in general. Participants often encounter infographics and one participant indicated that while they agree with the sentiment of these posts, not even one pulls them in. They felt that these posts “virtue signal” to people and tell them to do their part, when big corporations should bear the brunt of the responsibility. Another frustration about the current communication is its performative nature. While at one point in time the content was more enticing, it now appears to be about public image and is repetitive. Another participant just taps through these posts because it is not what they are on Instagram for. One participant indicated that they disregard information on social media and only value content produced by reputable news sources, like the New York Times. This establishes extensive room for growth in climate change communication on social media.

Activity Responses

When participants were asked to rank each social media post in the sample on a 1-10 scale indicating its ability to empower, the posts with the highest number were more likely to have been categorized as pessimistic posts. A few notable emotions evoked by these posts were upset, motivated, fearful, nervous, sad, and shocked. The posts with the lowest number were more likely to have been categorized as optimistic posts. A few notable emotions evoked by these posts were uninspired, unrelated, disassociated, and trite.

Participants were surprised that they felt more empowered by pessimistic posts because they previously thought that they gravitated towards optimistic content. There is a disconnect between what most participants expected to be empowered by and what they were empowered by during the focus group. One participant said, “when I get on social media, I don’t like feeling like it’s doomsday or like I’m being scolded. I want to go on social media to be uplifted and I feel like whenever I see stuff that might be more grim then it turns me away.” They indicated that they did not want a reality check on social media. Another participant explained the importance of walking the line between scaring people and giving them hope to move forward. They suggested that overwhelmingly negative content is hard to grasp and can lead to people pushing the issue to the back of their minds and then seeking out other content that will make them feel better. However, other participants were more vocal about why the pessimistic social media posts were more empowering. They established that darker posts are more likely to grab attention and that people need to see something negative to get involved because optimistic content allows them to pretend that it is going well, and their engagement is not required. Ultimately, a desire for a middle ground between optimism and pessimism was deemed the best approach.

Personal Appeal and Specificity

Personal appeal and specificity were deemed one of the most important elements in a social media post about climate change. One participant who believes in the power of relatable content on the local level said, “I feel like I care about the issue because of the experiences I’ve had, and I want my kids to have that and if I can see exactly what I love doing and some sort of visual like we could lose this, that’s something that I would care more about.” Participants expressed interest in content that is already connected to them and is about issues that will have a significant impact on them. Information about other locations feels irrelevant and they would pay more attention to content about places they are connected to. One participant who ranked a post about flooding high said, “I just have a lot of memories associated with Hurricane Harvey, almost got into a horrific car accident, and also some friends that had their houses destroyed. I’m not even from Houston but I know people there.” Another participant said, “Being from right outside of Boston there have been a lot of graphics about the cities on the water pretty much, so how much of it will be underwater in the next thirty years and that’s a big thing to think about especially when Massachusetts is trying to pass alternative energy and so trying to balance both and what we can do but also planning for the future.” The significance of ripple effects is established as key. One participant said:

Sometimes the world is such a big place that when you’re going “this is destroying the earth,” someone’s like “what could I possibly do sitting in a dorm room?” Versus you could go to this community meeting and go “I drink the public water here” or something is a ballot initiative in your state, and you can go vote on that. Little things that make a big difference in the long run but are just in your little part of the world.

Overall, participants felt most empowered by content that they could relate to and act on locally.

Celebrities

Another element that participants advocated for was the use of celebrities in content. One participant felt empowered by a post simply because he admired the man who was quoted. Other participants referenced Leonardo DiCaprio and Ian Somerhalder as celebrities who have used their status to have a societal impact. Another participant referenced Matthew McConaughey’s tequila brand. They indicated that their desire to buy the tequila was rooted in admiration for him rather than the product itself, suggesting that many people will do whatever celebrities tell them to do and this intense idolization would be beneficial for climate change communicators to tap into.

Call to Action

Another vital element in a social media post about climate change is a specific call to action. Participants indicated frustration towards general messages about creating change that do not outline steps to create that change. One participant said, “you actually have to give them a reasonable form of action and not just hope” and that they would be more likely to look at something if it says something can be done. Hope is still an essential component; people want proof that something works to commit to taking those steps. Ben and Jerry’s was referenced as a positive example because the company gets attention by scaring, then informs on what viewers can do about the issue that scared them. Some participants advocated for the promotion of petitions or places to donate, indicating that they liked the idea of a quick, easy, online way to feel as though they have contributed. However, some already scroll past the links to organizations’ pages and others say they are not willing to contribute money to the cause as a college student. One participant saw being generally aware and voting as the key to engagement on the issue. Another participant indicated that one way that social media posts can serve as calls to action is by generating awareness about protests. Protests with high attendance put pressure on politicians. Another participant expressed admiration for posts that provide contact information and templates for representatives. While participants’ thoughts on what calls to action are most empowering, they all support the notion that these calls to action must be specific and feasible.

Extensive Text

One major issue in climate change communication on social media is extensive text. Participants indicated that they were unwilling to read significant amounts of text and would likely scroll past the post. One participant said that 10 to 12 words in a quote was the maximum number for it to be effective. When asked why one post was not empowering, they responded: “this is bad, there were a lot of words.” They were met with agreement from the other participants. Participants generally did not want to think too hard while on social media which means that lengthy text got ignored.

Political Messaging

Participants also shared that they dislike political messaging in climate change communication. One participant said that sources lose credibility when they blame one political party for climate change. Another participant said that they don’t think climate change and being liberal should be so heavily associated. Another followed up on this comment, saying “you can have the same end goal and just different paths to get there.” Participants desired a unifying rather than polarizing approach to climate change communication.

V. Discussion

This study intended to determine whether optimistic or pessimistic climate change communication is more effective in engaging and empowering young audiences. The results of the focus groups indicate that pessimistic posts are slightly more effective. However, both focus groups emphasized the importance of other elements besides pessimism and optimism. The results indicate that personal appeal, specificity, and a call to action are the most important components to climate change communication.

Emotions such as nervousness that were associated with some of the most empowering posts suggest a potential connection between fear and empowerment that contradicts previous literature. The literature review indicates that young people generally feel overwhelmed by pessimistic content. The results of this focus group indicate that pessimistic content has more power to catch attention and send a message quickly. However, the results indicate that pessimistic messaging also risks being ignored. This is explained by the mood management theory established in the literature review. Participants often scroll past climate change communication or immediately seek out content that makes them feel better after viewing climate change communication because people are wired to optimize their moods. The importance of providing a path forward that was established in the literature review was made evident by the results of the focus groups. Participants felt strongly about the need for a specific call to action in both pessimistic and optimistic climate change communication.

The results indicate that personal appeal and specificity are essential components to empowering and engaging content. Previous research suggested that personal and localized storytelling regarding climate change is effective because it is more relatable and therefore understandable. This explains why participants felt more empowered by content that had some relation to a personal experience of theirs, such as a natural disaster or living on the coast and felt disengaged from content about other states. Participants mimicked the exact feelings of those in previous research studies by spending extensive time discussing their lack of interest in content that was not directly relevant to them and content that did not provide them with any practical solution.

The literature review also suggests that people place the impacts of climate change at a psychological distance. This explains why participants admitted that they often scroll past climate communication and are more likely to engage if the content would have a significant impact on them. The only way to remove psychological distance is to establish a direct connection between a viewer and content. The results indicate that personal appeal is an essential component to this, and that personal appeal can be incorporated into specific calls to action on the local level.

VI. Conclusion

This study indicates that pessimistic content regarding climate change cannot be abandoned but must be strategically created. While the nuances of the issue of climate change communication were previously generally understood, this study established numerous specific essential components. Participants with different educational backgrounds, personal histories, and passions all came to various agreements on what elements of climate change content are empowering despite not finding the same specific posts the most empowering. Climate change communications content should establish a fear-inducing problem that directly relates to its intended audience and provide a specific and accessible call to action. Content should not include extensive text or hyper political messaging.

The study included students at Elon University across schools and majors, but the findings cannot provide a full picture of the Elon student body or greater college student demographic. Furthermore, the ideas shared in the focus group might vary from the thoughts that participants would be willing to share had they been with close friends in an environment not previously established as a place for academic research. This self-censorship or pressure to appeal to peers serves as a limitation of these findings. However, the researcher established a safe environment for the free flow of ideas to hinder this limitation’s power. Furthermore, this study only exposed students to ten social media posts due to time constraints. These ten social media posts, while strategically selected, could not represent all existing climate change communication content.

These findings suggest that further research regarding how to craft personal appeals and calls to action in climate change communication would be beneficial. This research was intended to differentiate between pessimistic and optimistic climate change communication, but the flow of discussion indicated that young people feel most passionate about specificity and calls to action that can exist in pessimistic and optimistic posts. Participants discussed the effectiveness of linking petitions and donation pages and promoting protests. Therefore, research into what specific calls to action are most impactful has the potential to strengthen climate change communication moving forward. Furthermore, research into how to craft personal appeals would be advantageous as society seeks to save the planet.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Dr. Harlen Makemson, who provided incredible insight and guidance throughout the development of this project. Another thank you to all those who participated thoughtfully in my focus groups.

References

Ejaz, W., & Najam, A. (2023). The Global South and climate coverage: From news taker to news maker. Social Media + Society, 9(2), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051231177904

Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115.

Hawley, E., & Mocatta, G. (2022). “Fact-based dreaming” as climate communication. Popular Communication, 20(2), 91–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/15405702.2021.1994576

Hibberd, M., & Nguyen, A. (2013). Climate change communications & young people in the Kingdom: A reception study. International Journal of Media & Cultural Politics, 9(1), 27–46. https://doi.org/10.1386/macp.9.1.27_1

Kim, H., Armsworth, P. R., Masuda, Y. J., & Chang, C. H. (2024). US-based and international environmental nongovernmental organizations use social media, but few have large audiences online. Conservation Science and Practice, 6(1), e13037. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.13037

Lee, K., & Barnett, J. (2022). Adolescents’ representations of climate change: Exploring the self-other thema in a focus group study. Environmental Communication, 16(3), 408–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2021.2023202

León, B., Bourk, M., Finkler, W., Boykoff, M., & Davis, L. S. (2023). Strategies for climate change communication through social media: Objectives, approach, and interaction. Media International Australia (8/1/07-Current), 188(1), 112–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X211038004

Shelter, C. (2021). Exploring climate narratives: The link between animal agriculture and climate change in U.S. media. The Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications, 12(2), 91–102. https://eloncdn.blob.core.windows.net/eu3/sites/153/2021/12/08-ShelterV2.pdf

Sims, J. M. (2010). A brief review of the Belmont Report. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing, 29(4), 173–174. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCC.0b013e3181de9ec5

Skurka, C., Romero-Canyas, R., Joo, H. H., & Niederdeppe, J. (2022). Choose your own emotion: Predictors of selective exposure to emotion-inducing climate messages. Environmental Communication, 16(3), 424–431. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2022.2083207

Skurka, C., Romero-Canyas, R., Joo, H. H., Acup, D., & Niederdeppe, J. (2022). Emotional appeals, climate change, and young adults: A direct replication of Skurka et al. (2018). Human Communication Research, 48(1), 147–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqab013