- Home

- Academics

- Communications

- The Elon Journal

- Full Archive

- Fall 2024

- Fall 2024: Gianna Smurro

Fall 2024: Gianna Smurro

Digital Deceptions: Assessing the Influence of Deepfake Technology on Identifying Political Misinformation on Social Media

Gianna Smurro

Journalism and Cinema and Television Arts, Elon University

Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements in an undergraduate senior capstone course in communications

Abstract

AI-generated deepfake videos contribute to the spread of misinformation and disinformation on social media platforms, emphasizing the urgent need for comprehensive mitigation strategies and enhanced media literacy. Deepfakes continue to erode trust in social media content and contribute to political polarization. An experimental survey was conducted using incomplete disclosure to understand how social media users process and evaluate the videos they watch on social media. Findings reveal a multifaceted relationship between individual cognitive processes, pre-existing political biases, and the persuasive effectiveness of deepfake media. Varying degrees of skepticism were demonstrated toward political deepfake videos. Political bias influences how people judge the authenticity of content, making deepfake technology even more of a concern because of its ability to exploit such biases in our thinking. This necessitates both social media platforms and media consumers to recognize and evaluate deceptive content to uphold democratic functions and integrity.

Keywords: deepfake, Artificial Intelligence (AI), social media, misinformation, disinformation, media literacy, political bias, cognitive processing

Email: gsmurro@elon.edu

I. Introduction

Deepfakes leverage machine learning and artificial intelligence to create shareable media that threatens the integrity of information on social media platforms. This manipulation encompasses various forms such as videos, audio, and images portraying a deceptive authenticity. Individuals can be made to say or do things they never did by distorting and altering videos to look believable (Kietzmann et al., 2020). Such media content poses a problem, as it is often shared among the public through social media platforms. A small group of manipulators can create deepfakes and share them on social media. There, they are easily shared by unsuspecting users who unknowingly perpetuate the dissemination of deceptive content (Vaccari & Chadwick, 2020). This propagation of fabricated information erodes trust in social media platforms. It extends its influence to reduce trust in various other information sources through spreading misinformation and disinformation (Menczer et al., 2023).

The pervasiveness of deepfakes on social media threatens the integrity of information on such platforms and requires immediate attention and comprehensive strategies. Exposure to untrustworthy content, erosion of political dependability, and psychological implications highlight a need to understand better how people consume and evaluate such media (Hancock & Bailenson, 2021). All of this speaks to the need to explore the nuanced dynamics of user perception and broader societal consequences, paving the way for effective countermeasures and safeguards against the deceptive influence of deepfakes on social media. This paper will explore individuals’ abilities to distinguish political deepfakes on social media platforms and the cognitive processes used during such determination and evaluation.

II. Literature Review

Deepfakes, “leverage powerful techniques from machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) to manipulate or generate visual and audio content with a high potential to deceive” (Kietzmann et al., 2020, p. 136). The broad term deepfake includes videos, audio, and images altered to portray a person or event differently. Manipulation can occur through face swapping, voice alteration, fake social media profiles, and other currently evolving media. Focusing specifically on deepfake videos, a pre-existing video of a person can be distorted to make the person say something different, speak with a different tone or accent, alter movement, or even look like a different person. These distorted videos are typically generated from videos of public figures such as politicians, celebrities, athletes, or other prominent figures and are often shared without a disclaimer of such misrepresentation (Westerlund, 2019).

The term deepfake combines “deep learning” and “fake.” The former refers to algorithms that enable the creation of convincing and humanistic visual and auditory media through analyzing large datasets, and the latter relates to untrue content (Khoo et al., 2021). Photorealism is attainable because these datasets comprise hundreds to thousands of images of a person available online. While image manipulation has been possible for many years due to platforms such as Photoshop, what differentiates and popularizes deepfakes is the accessibility of their creation (Hofer & Swan, 2005). Applications such as DeepFaceLab, Deepfakes Web, and FakeApp are all minimal-cost or free software that can be downloaded and used on most mobile devices (Kietzman et al., 2020). With the potential to spread disinformation through avenues such as social media, deepfakes pose a significant problem in the circulation of deceptive media.

Users must distinguish between misinformation and disinformation and deepfakes’ role in both. Misinformation is false, inaccurate, or misleading information that is unintentionally spread, while disinformation is spread intentionally with the knowledge that it is untrue (Rhodes, 2021). This implication for deepfakes is that a few people may create deepfake videos; however, once posted on social media platforms, they can be consumed and shared by other social media users unaware of the falsity of what they share (Hancock & Bailenson, 2021).

Spreading fabricated content diminishes social media users’ trust in posts across social platforms and extends to eroding trust in other information sources. Though a deepfake may not entirely deceive its viewer, it creates uncertainty that leads to reduced trust in news on social media. The currently unknown long-term impacts of this uncertainty emphasize the importance of addressing deepfakes in the context of online civic culture.

Social Media Literacy

Given that social media platforms serve as prominent channels for disseminating deepfake videos, a concern arises: users need a certain level of evaluative literacy to discern the credibility of the content they consume. The overarching term of digital literacy refers to competencies related to the skilled use of computers and information technology. It is characterized by the ability to understand, evaluate, and integrate information that technology delivers (Leaning, 2019).

Skill in navigating digital media enhances social media users’ capacity to discern the authenticity of the videos they encounter. More specifically, media and information literacy equip people with the skills to analyze and critically interpret media content (Rhodes, 2021). A positive association between frequent exposure to deepfakes and concerns about deepfakes leads to increased skepticism toward information on social media platforms. This highlights the crucial role of media literacy for individuals on social media platforms.

In 2023, with 19% of U.S. adults often receiving their news from social media and 31% sometimes consuming news on social media, such platforms influence public perception in disseminating news and information in the digital age. The top five social media platforms used by U.S. adults who regularly obtained news from social media were Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, TikTok, and X (Twitter) (Liedke & Wang, 2023). Without media literacy, individuals may be more susceptible to misinformation and manipulation on these platforms. They may struggle to distinguish between credible news sources and misleading content, compromising the reliability and accuracy of the information they consume (Yadlin-Segal & Oppenheim, 2020).

Social media algorithms meant to boost user interaction might unintentionally promote deepfakes. Moderation challenges on these platforms also complicate identifying and removing deepfakes (Hancock & Bailenson, 2021). Addressing issues associated with deepfakes on social media requires widespread media literacy and responsible content-sharing practices.

Impact of Deepfakes

Deepfakes pose various economic, political, and psychological challenges. There are growing concerns that deepfakes pose a global threat to election integrity. These arise as deepfake creation software advances, making them more sophisticated and accessible. The Federal Communications Commission recently ruled against AI-generated voices in robocalls in response to a robocall impersonating President Joe Biden in February 2024. However, the narrative surrounding deepfakes may be more detrimental than the deepfakes themselves. This creates fear and undermines trust in information by creating a “liar’s dividend,” underscoring regulatory challenges and the potential for deepfakes to create and spread disinformation (Mirza, 2024). The suggestion that the fear surrounding deepfakes may be more corrosive than the manipulations themselves further fuels such concerns (Hancock & Bailenson, 2021).

Scholars have noted that the social and psychological aspects of deepfake technology highlight the challenge of detecting evolving algorithms. The rapid evolution of deepfake algorithms is outpacing efforts to detect them (Kietzman et al., 2020). Few empirical studies have been published on this topic, emphasizing the urgency of investigating the psychological processes and consequences of AI-modified video content. Beyond economic and political implications, deepfakes pose an epistemic threat by diminishing the credibility of visual media, resulting in reduced trust in news sources due to perceived uncertainty. The potential modification of memories and attitudes through exposure to deepfakes adds a layer of complexity to the societal consequences of these manipulations (Hancock & Bailenson, 2021).

These observations and insights weave a narrative of deepfakes as a pervasive threat to the integrity of information on social media. They require immediate attention and comprehensive combative strategies. The sharing of untrustworthy content, the decline of political integrity, and the psychological implications highlight the cruciality of robust research, regulation, and responsible platform practices (Kietzmann et al., 2020). The harmful effects of deepfakes emphasize the urgent need for collective actions to reduce their spread and safeguard trust in the digital era.

The Role of Political Bias in Misinformation

Rhodes (2021) investigated the effects of simulated partisan filter bubbles on participants’ ability to discern misinformation on social media platforms. Filter bubbles are created on social media platforms when algorithms learn users’ content preferences and display content that aligns with those preferences, aiming to increase the time spent on a platform (Mims, 2016). Participants were randomly assigned to homogeneous or heterogeneous groups. The homogeneous group read articles aligned with their political leaning (Democrat or Republican), while the heterogeneous group read articles that appealed to both political leanings. The results indicated that participants in the homogeneous group were more likely to rate misinformation as believable than their peers.

Using a survey experiment design, participants rated the believability of articles on a 5-point Likert scale, which facilitated the construction of an OLS regression model to determine believability. This study’s design follows a similar structure yet examines in greater depth the impact of deepfake technology in evaluating political content on social media.

III. Methods

RQ1: How do participants’ perceptions of the authenticity of deepfake videos compare to their assessments of genuine content?

RQ2: To what extent do individuals engage in heuristic (immediate and intuitive) and systematic (measured and analytical) processing when evaluating political content on social media?

This study employed incomplete disclosure to understand how social media users process and evaluate the videos they watch on social media. Thirty participants were recruited through snowball sampling. The survey was distributed to students in Elon University networks (such as the School of Communications, Elon University Fellows, identity networks, and student organizations), and participants were encouraged to share the survey with other students who might be interested. The survey, launched on April 15, 2024, exposed participants to real and deepfake videos in a Qualtrics-administered survey. All participants were notified in the consent form that the study aimed to see how people evaluate the political content they view on social media. This included an acknowledgment of deception. The participants did not receive prior notification that some of the videos contained misinformation. The study design was reviewed by the university’s Institutional Review Board before data collection began.

After collecting demographic data, the survey exposed the participants to four videos, each under 30 seconds, that were a mix of deepfakes and real videos. Two of the videos were real, and two were deepfakes. The videos featured politicians Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ron DeSantis, Donald Trump, and Joe Biden. Each participant watched the same videos and then answered three questions about the videos, providing evaluative responses on a five-point Likert scale. The questions asked participants about how truthful they considered the videos to assess their believability: “Rate the effectiveness of this video, with 0 being ‘This is not effective’ and 5 being ‘This is effective’”; “Regarding the accuracy of the video, how likely are you to share this video with others, with 0 being ‘Unlikely to share’ and 5 being ‘Likely to share?’”; “How believable do you consider this video, with 0 being ‘This is not true’ and 5 being ‘This is true?’.”

Selection of Real and Deepfake Videos

Four videos, two real and two deepfakes, were selected after looking through social media platforms such as Instagram and Facebook.

The first video shown to participants was an actual Instagram story post about capitalism and socialism on Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s Instagram account. She was responding to a question she received from a follower who asked, “How do you respond when people accuse you of being a ‘socialist?’” She responded that most people do not know what capitalism or socialism is and that most people are not capitalists because they do not have capitalist money. She also zooms in and out on her face to emphasize words such as “don’t really know,” “most people,” “socialism,” “capitalists,” and “billionaires.”

The second video was a deepfake of Ron DeSantis. It shows footage from the 2022 Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC), with his voice dubbed over. This video featured DeSantis critiquing his political actions. The deepfake shows DeSantis discussing topics and actions like signing red flag gun confiscations into law, state-mandated vaccinations, claiming victory over Disney while they’re still “woke, self-governing, and tax-exempt,” receiving donations from Citadel, hiring an agent connected to George Soros, and criticizing his lack of support for someone implied to be Donald Trump. He did not say these things in the original clip, and the audio did not synchronize with the video. The original video discussed topics such as increasing border security, ensuring the integrity of elections, and combatting inflation.

The third video was a real video of Donald Trump from an April 2020 press conference at the White House, where he discussed the possibility of injecting a chemical disinfectant to treat coronavirus. In this video, he does not look directly into the camera but instead frequently turns his head to his right to address people in the room. It was recorded and shared by news organizations such as MSNBC, CBS, and TODAY, among many others.

The fourth and final video was a deepfake of Joe Biden. The audio is dubbed over a video from a press conference. This deepfake video closely synchronizes the audio with Biden’s facial and body movements. Biden references “Biden-omics,” how people “won’t have to leave home now to get a good job,” and how he ran his campaign from his basement. He did not say these things in the original video.

After completing the experiment, participants answered questions to assess their heuristic and systematic information processing. Heuristic processing involves quick, intuitive judgments based on easily recognized information. Systematic processing involves a more analytical evaluation of information. Some of the processing questions were adapted from Griffin et al. (2002), and the Heuristic Processing and Systematic Processing scales were adapted from Rhodes (2021). The answers each were measured using a five-point Likert scale.

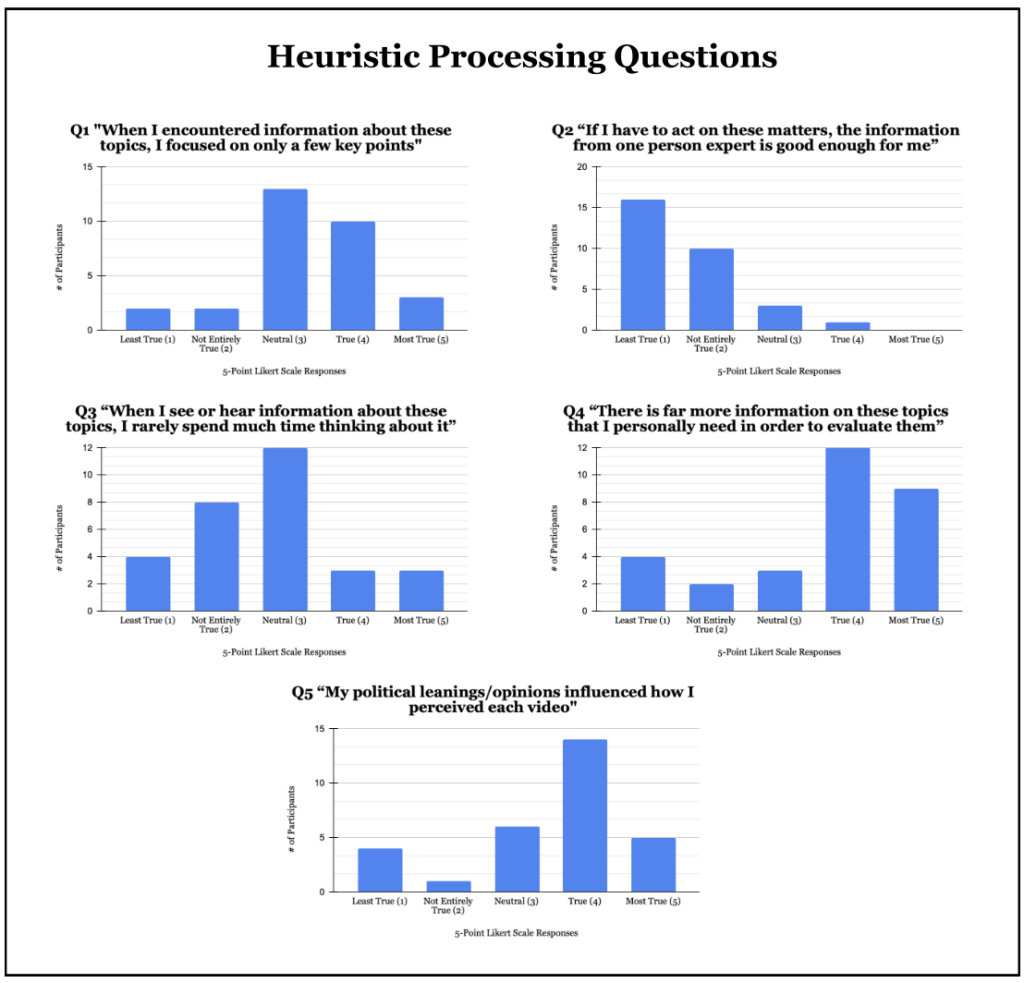

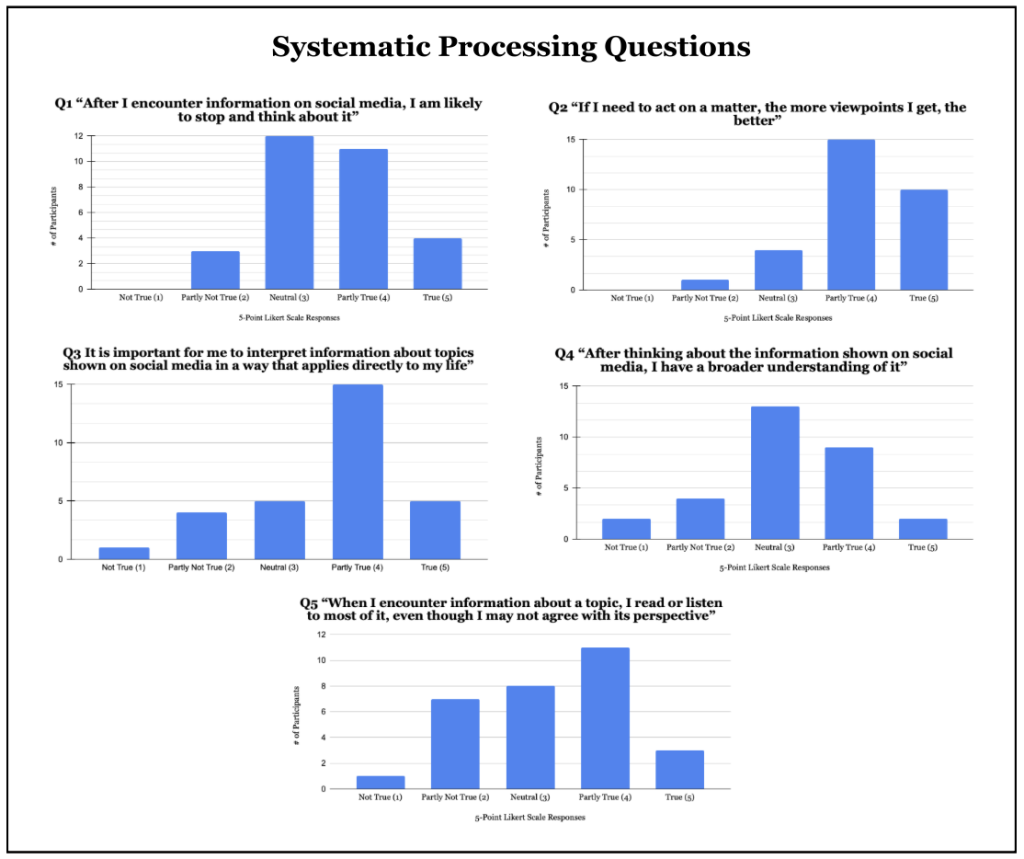

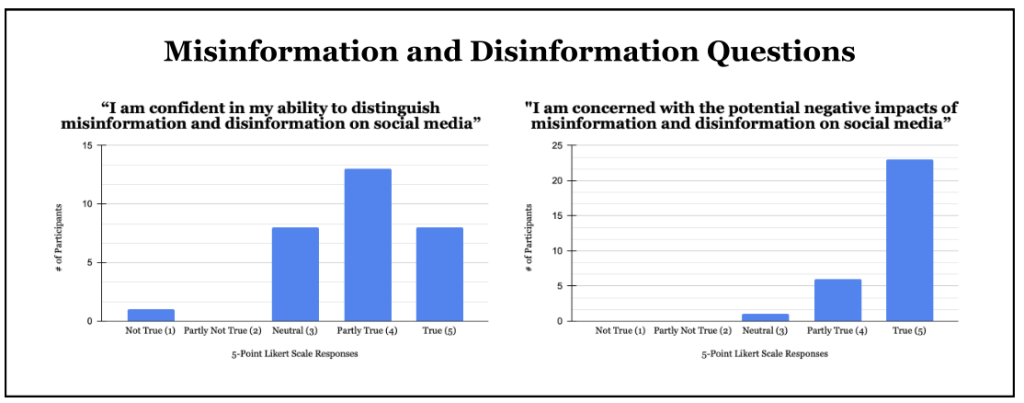

The Heuristic Processing scale is composed of these questions: “When I encountered information about these topics, I focused on only a few key points;” “If I have to act on these matters, the information from one person expert is good enough for me;” “When I see or hear information about these topics, I rarely spend much time thinking about it;” “There is far more information on these topics that I personally need in order to evaluate them;” and “My political leanings/opinions influenced how I perceived each video.” The Systematic Processing scale is composed of these questions: “After I encounter information on social media, I am likely to stop and think about it;” “If I need to act on a matter, the more viewpoints I get, the better;” “It is important for me to interpret information about topics shown on social media in a way that applies directly to my life;” “After thinking about the information shown on social media, I have a broader understanding of it;” and “When I encounter information about a topic, I read or listen to most of it, even though I may not agree with its perspective,” (Griffin et al., 2002). The survey concluded with two final five-point Likert scale questions related to misinformation and disinformation: “I am confident in my ability to distinguish misinformation and disinformation on social media;” and “I am concerned with the potential negative impacts of misinformation and disinformation on social media.”

These questions allowed the analysis of the participants’ agreeability with the questions above and gauged their susceptibility to political misinformation.

IV. Results

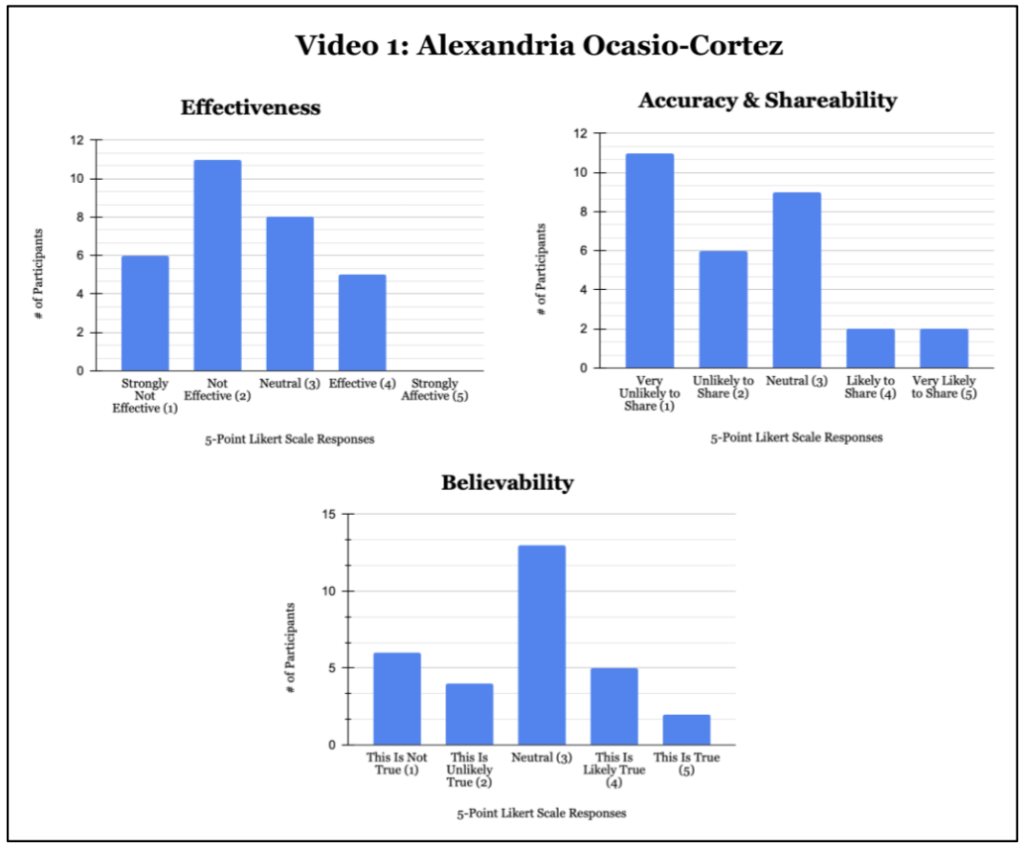

Figure 1 shows participants’ assessment of the Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Instagram story video based on effectiveness, likelihood of sharing, and believability. Results indicate that most participants rated the video as strongly not effective or not effective, suggesting it did not adequately resonate with the participants. Like the effectiveness rating, most participants expressed hesitancy to share the video, implying a lack of perceived value. However, the believability ratings are more evenly distributed, with most participants selecting the neutral option.

Figure 1

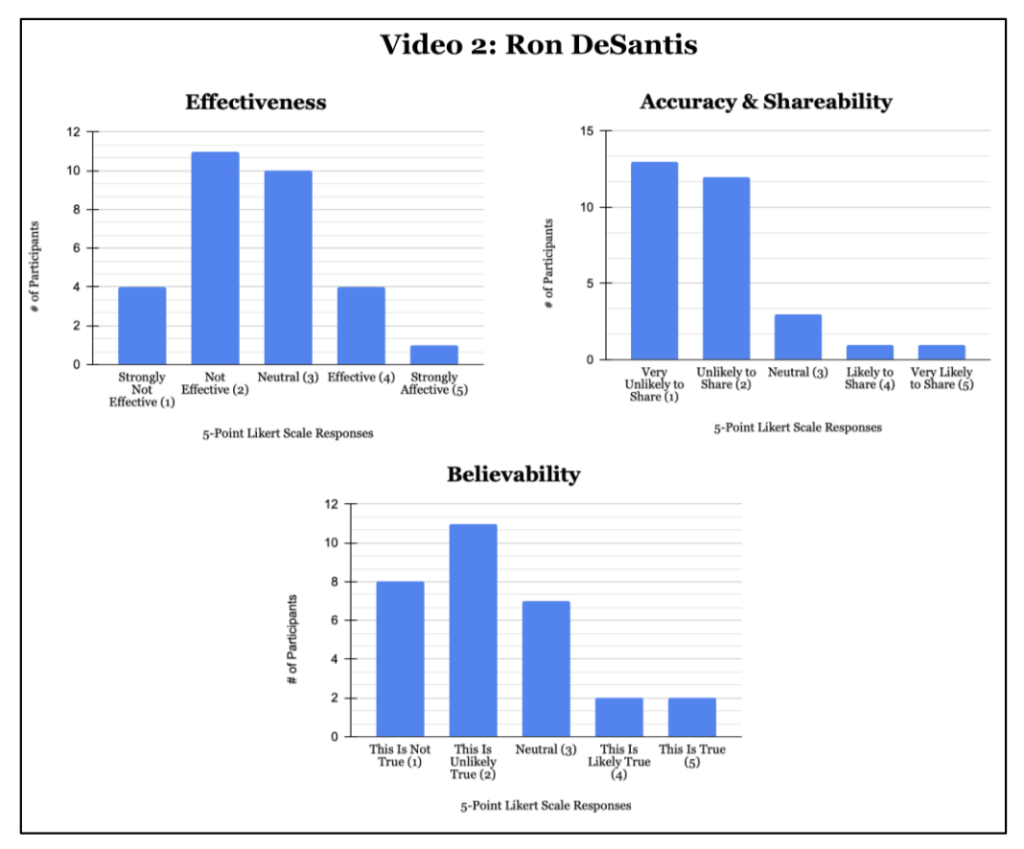

Figure 2 shows participants’ assessment of the Ron DeSantis deepfake CPAC video. Most viewers did not find it to be persuasive or impactful. A notable number of participants answered neutrally regarding the video’s effectiveness, suggesting a degree of uncertainty among them. The data was strongly right-skewed for the likelihood of sharing, showing a strong reluctance to share the video’s content. In line with the following results, only a small minority of participants found the video to be believable, with the majority rating it as not true or unlikely true.

Figure 2

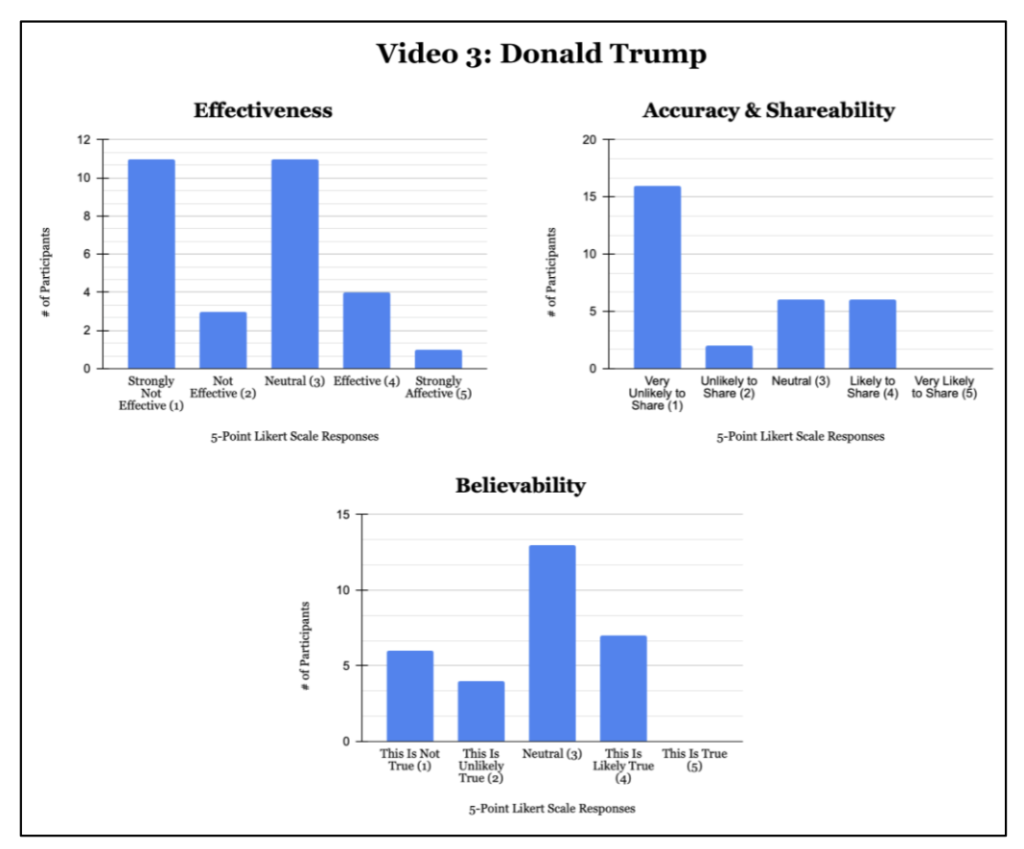

Figure 3 shows participants’ assessment of the Donald Trump coronavirus press conference video. Despite the video’s truthfulness, participants again showed a negative response, with the majority rating the video as strongly not effective and neutral; an equal number of participants rated it as strongly not effective and neutral. Interestingly, most participants exhibited a strong inclination not to share the video. Responses regarding the believability of the video were varied, though, with many participants favoring a neutral response. These results indicate skepticism but not definitive decisions regarding truthfulness.

Figure 3

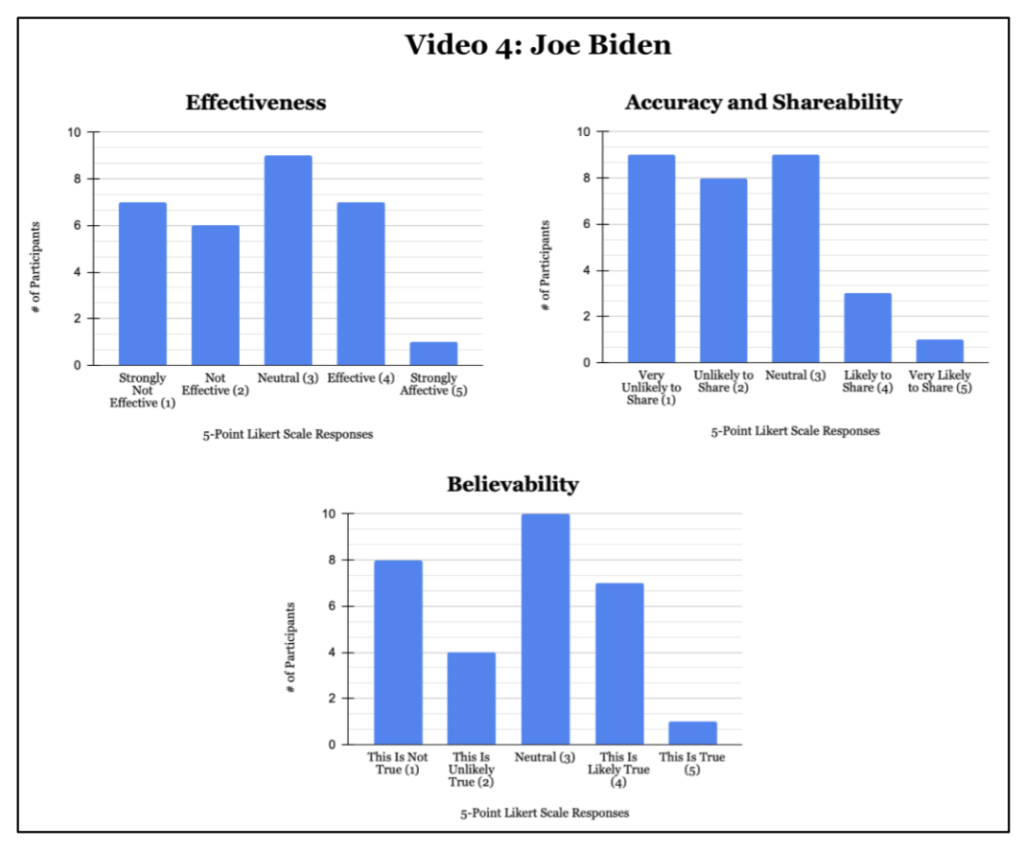

Figure 4 shows participants’ assessment of the Joe Biden deepfake press conference video. Though the data leans slightly toward skepticism of the video’s effectiveness, the overall results indicate mixed perceptions. Most participants expressed being either very unlikely to share or unlikely to share, with an equal number of participants indicating neutral and very unlikely responses. The responses regarding believability also reflected a range of opinions. A considerable number of participants remained neutral, and many participants expressed skepticism and disbelief in the video’s authenticity. However, it is worth noting that a sizable minority considered the video likely true or true, indicating that deepfake technology can still successfully deceive some viewers.

Figure 4

As deepfake technology continues to become more advanced, there is a growing potential for its misuse by spreading misinformation. However, the findings of this study suggest that although deepfake technology may initially grab the attention of its viewers, it often fails to convince and engage them effectively. Though deepfakes may not entirely deceive their viewers, exposure to such information can still influence future generalizations or decision-making (Vaccari & Chadwick, 2020). Deepfake videos of people unknown to a viewer may hold greater deceptive power as the audience is less familiar with the vocal qualities or mannerisms of the subject. Given the prominence of each politician, there is a high likelihood of familiarity with each politician in the videos.

Such familiarity with the politicians highlights this study’s limitation of potential bias in participants’ responses. Pre-existing political biases regarding each politician may have influenced how the respondents evaluated the videos. Those with a negative view of one of the politicians may have been inclined to answer with lower indications of effectiveness, shareability, and believability, regardless of the video’s content, and vice versa for those with a positive view of a politician. Such potential for bias combined with deepfake media creates a concerning social implication: political polarization can make evaluating the truthfulness of content more complex, thus eroding trust in the media.

This highlights the need for increased media literacy and the importance of emphasizing critical evaluation, regardless of how presented information relates to personal or political beliefs. Promoting practices of inquiry across social media platforms can mitigate the negative consequences of deepfakes on political and public discourse in a world with rapidly evolving AI technology.

Post-Exposure: Heuristic Processing

The responses to the Heuristic Processing questions, shown in Figure 5, indicated varying degrees of reliance on cognitive shortcuts. Most participants indicated a neutral position regarding whether they focused on a few key points in each video, suggesting moderate heuristic processing. Rather than relying solely on authority-based heuristics, the participants strongly disagreed that information from one expert is sufficient to act on political matters. This suggests greater deliberation before making decisions and the possibility of seeking out other sources of information. Most participants selected a “3” when evaluating how much time they spent thinking about the information in the videos, indicating moderate engagement with the content. A notable number of participants strongly agreed that they needed more information before evaluating the topics discussed in the videos. This implies a reliance on availability heuristics, as their assessment of believability came from the presented information rather than being synthesized with prior knowledge.

The overall dependence on heuristic processing suggests that individuals may not thoroughly evaluate information, especially if the presented information strongly adheres to or goes against their existing beliefs. The data for whether the participants’ political leanings or opinions influenced their perception of the videos was strongly left-skewed, with 14 respondents indicating mostly true and five respondents indicating true. Such strong self-recognition of political leanings highlights susceptibility to confirmation bias.

Figure 5

Participants’ responses to understanding engagement questions, as shown in Figure 6, indicated a moderate to high level of agreement. Thirteen respondents indicated a “3” when evaluating whether they have a broader understanding of presented information after thinking about it, suggesting reflective processing. Most respondents agreed that they read or listened to most of the information presented, even if they may not agree with its perspective, highlighting a willingness to engage with diverse viewpoints. Most participants also had a moderate inclination to stop and think about the content they encounter on social media, aligning with how fifteen respondents strongly agreed that obtaining multiple viewpoints is important when acting on a matter. Fifteen participants also indicated that it is important to interpret information from social media in a way that directly applies to their lives, highlighting the significance of personal relevance when processing information. The data suggests that participants exhibit a high level of active engagement with content on social media.

Figure 6

When the participants’ responses to the heuristic and systematic processing questions are compared, even though the responses to the sets of questions appear contradictory, they reveal a synthesis of processing strategies. The answers participants provided depended on how the information was presented, its complexity, and their personal understandings or beliefs. This study’s results emphasize the importance of promoting critical media literacy for social information presented on social media. One of the most concerning aspects this research reveals is the impact of political bias on participants’ responses. There is a demonstrated personal awareness of political bias in participants’ responses, yet this bias can still influence the interpretation of presented information. Addressing this issue requires enhanced critical evaluation of media and a greater understanding of political bias regarding social media content.

Acknowledging the different degrees to which individuals cognitively process presented information can increase the detection of deepfakes and misinformation on social media. By understanding the differences between heuristic and systematic processing, social media platforms can leverage tools such as educational campaigns and detection software to alert users of deceptive content. AI-powered algorithms generate feeds that are agreeable to a user’s preferences, thus posing the issue of potentially propagating increasingly polarized feeds (Rhodes, 2021). Incorporating mechanisms to disrupt echo chambers and mitigate resulting confirmation bias can enhance users’ ability to detect deepfake technology and misinformation.

One limitation of this study, which could not have been prevented, is the presence of social desirability and self-reporting bias. This is when respondents answer questions in a way they perceive is socially acceptable or desirable. Though this survey was anonymous, individuals may have hesitated to disclose behaviors or opinions they perceived as socially undesirable. The final two Likert scale questions asked in the survey were, “I am confident in my ability to distinguish misinformation and disinformation on social media,” and “I am concerned with the potential negative impacts of misinformation and disinformation on social media.” The data for both questions, as shown in Figure 7, was strongly left-skewed. Thirteen respondents indicated true, and 8 indicated very true for the first question, while 23 indicated very true for the question regarding concerns about misinformation and disinformation. It is unclear whether these responses are accurate indications of the participants’ beliefs or a reflection of the current social narrative of the dangers regarding the spread of false content. Though this may leave uncertainty regarding the authenticity of participants’ beliefs, the data serves as a point from which to evaluate individuals’ critical information processing techniques.

Figure 7

V. Conclusion

The implications of this research can be concluded in three main takeaways: the negative impact of political bias in evaluating political information on social media, the urgent need for comprehensive mitigation strategies, and the critical role of media literacy. Deepfakes pose a significant threat to the integrity of content on social media. Social media users must possess a degree of critical hesitation when consuming content on social media platforms. Media literacy is associated with individuals’ confidence in evaluating information. Thus, an untrusting public is created (Ahmed, 2021). This is heightened by the inevitability of biases entering cognitive processes.

Participants’ perceptions of the authenticity of deepfake videos varied compared to their assessments of genuine content, indicating a level of skepticism and uncertainty. This underscores the challenges in discerning manipulated media and suggests the potential for deepfake technology to exploit vulnerabilities in opinion formation. With social media’s global reach, deepfakes can influence opinions and perceptions worldwide, contributing to an erosion of trust in digital content (Hancock & Bailenson, 2021). As deepfakes become more sophisticated and challenging to distinguish, the depletion of assurance in information sources increases (Vaccari & Chadwick, 2020). The deliberate creation and dissemination of deceptive content undermines the foundation of trust essential for a functioning democracy.

Individuals demonstrated varying degrees of heuristic and systematic processing when evaluating political content on social media, highlighting the complexity of information evaluation. While some relied on quick, intuitive judgments, others engaged in more analytical evaluation, emphasizing the need for enhanced media literacy and critical evaluation skills to mitigate the spread of misinformation and deepfakes (Yadlin-Segal & Oppenheim, 2020).

Some of this study’s limitations include its small sample size and the fact that the survey interface did not resemble that of a social media platform. However, researchers can apply the insights from this study to future research. Further investigation is necessary to understand better the complexities of how individuals perceive and process political content on social media, especially when such content may spread misinformation and disinformation. Investigating the direct influence of political partisanship on the capacity to identify manipulated content presents an intriguing avenue for further research. It would be valuable to delve specifically into how people react to AI-generated political misinformation that is agreeable and disagreeable to their leanings and ideologies on social media platforms.

In an age of growing concerns regarding AI-generated deepfake technology and misinformation, both social media platforms and media consumers must act. Without accurate, trustworthy content, devising effective solutions to threats against democratic processes and societal trust in the media may prove futile.

Acknowledgements

I am incredibly grateful to my family and friends for their constant support and encouragement as I pursue my passions. I would also like to thank Dr. Glenn Scott for his guidance and mentorship, which have been invaluable in shaping this research into something I am truly proud of.

References

Ahmed, S. (2021). Navigating the maze: Deepfakes, cognitive ability, and social media news skepticism. New Media & Society, 25(5),1108–1129. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211019198

Griffin, R. J., Neuwirth, K., Giese, J., & Dunwoody, S. (2002). Linking the heuristic-systematic model and depth of processing. Communication Research, 29(6), 705-732. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365002237833

Hancock, J. T., & Bailenson, J. N. (2021). The social impact of deepfakes. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 24(3), 149–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365002237833

Hofer, M., & Swan, K. O. (2005). Digital image manipulation: A compelling means to engage students in discussion of point of view and perspective. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 5(3/4), 290-299.

Khoo, B., Phan, R. C. ‐W., & Lim, C. (2021). Deepfake attribution: On the source identification of artificially generated images. WIREs Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, 12(3). https://doi.org/10.1002/widm.1438

Kietzmann, J., Lee, L. W., McCarthy, I. P., & Kietzmann, T. C. (2020). Deepfakes: Trick or treat? Business Horizons, 63(2), 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2019.11.006

Leaning, M. (2019). An approach to digital literacy through the integration of media and information literacy. Media and Communication, 7(2), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v7i2.1931

Liedke, J., & Wang, L. (2023, November 15). Social Media and News Fact sheet. Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/fact-sheet/social-media-and-news-fact-sheet/#:~:text=News%20consumption%20on%20social%20media&text=Three%2Din%2Dten%20U.S.%20adults,%25

Menczer, F., Crandall, D., Ahn, Y.-Y., & Kapadia, A. (2023a). Addressing the harms of AI-generated inauthentic content. Nature Machine Intelligence, 5(7), 679–680. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-023-00690-w

Mims, C. (2017, October 22). How Facebook’s master algorithm powers the social network. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-facebooks-master-algorithm-powers-the-social-network-1508673600

Mirza, R. (2024, February 17). How AI-generated deepfakes threaten the 2024 election. Retrieved from https://journalistsresource.org/home/how-ai-deepfakes-threaten-the-2024-elections/#:~:text=We%20don%27t%20yet%20know,that%20most%20undermines%20election%20integrity.

Rhodes, S. C. (2021). Filter Bubbles, Echo Chambers, and Fake News: How social media conditions individuals to be less critical of political misinformation. Political Communication, 39(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2021.1910887

Vaccari, C., & Chadwick, A. (2020). Deepfakes and disinformation: Exploring the impact of synthetic political video on deception, uncertainty, and trust in news. Social Media + Society, 6(1), 205630512090340. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120903408

Westerlund, M. (2019). The emergence of deepfake technology: A Review. Technology Innovation Management Review, 9(11), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/1282

Yadlin-Segal, A., & Oppenheim, Y. (2020). Whose dystopia is it anyway? Deepfakes and social media regulation. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 27(1), 36–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856520923963