- Home

- Academics

- Communications

- The Elon Journal

- Full Archive

- Fall 2024

- Fall 2024: Katelyn Litvan

Fall 2024: Katelyn Litvan

Environmental Activism on Instagram: How Advocate Type and Image Type Influence Perceptions of the Advocate

Katelyn Litvan

Strategic Communications, Elon University

Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements in an undergraduate senior capstone course in communications

Abstract

Social media has transformed activism, especially in environmental issues, with platforms like Instagram serving as central hubs for awareness and action. This study employs a 3×3 between-participants experiment to examine the effects of advocate type and image type on perceptions of environmental advocates on Instagram. The findings showed that the intellectual advocate was perceived more authentic and more credible than both the celebrity advocate and the ordinary person advocate. The text-only graphic led to more perceptions of authenticity, credibility, homophily, and likability of the advocate than the pictures featuring the event scene, regardless of whether the advocate was present in the pictures or not. There were also interaction effects of advocate type and image type on perceived homophily and likability of the advocate.

Keywords: Instagram, environmental activism, advocate type, image type, persuasion

Email: klitvan@elon.edu

I. Introduction

Social media has revolutionized activism, particularly in environmental spheres, with platforms like Instagram becoming hubs for raising awareness and fostering change (Allsop, 2016; Wolbring & Gill, 2023). Within this digital landscape, the emergence of digital activism has become increasingly prominent, sparking conversations and driving social changes (Yuen & Tang, 2021). Unlike protests or letter campaigns, digital activism utilizes online platforms to mobilize individuals, rapidly share information, and amplify voices globally (University of Sussex, 2023). It provides a cost-effective way to reach a broad audience, disseminate messages, organize events, and build online communities (Hong & Kim, 2021). The power of social media to amplify voices, share stories, and mobilize communities has transformed the dynamics of environmental advocacy (Hermann et al., 2022). From grassroots campaigns to global movements, social media has become a catalyst for change, empowering individuals to become agents of environmental stewardship and sustainability (Abidin et al., 2020).

The rise of environmental activism on social media, particularly on Instagram, has demonstrated profound impact of digital connectivity on modern advocacy efforts (Hasler et al., 2020). Instagram has been credited by youth as an ideal platform to engage in education and activism about environmental issues and causes (Cortes-Ramos et al., 2021), largely due to its prominent use of visuals. Unlike other discussion-centric social platforms, Instagram motivates groups of followers to act through image dissemination (Appel et al., 2019). While any advocate can share environmental advocacy messages on Instagram, the effectiveness of these messages is subject to the influence of a variety of factors, such as the advocates’ identity and their choices of visuals incorporated into the posts. Therefore, this study intends to examine how three prominent types of environmental advocates – celebrity, intellectual, and ordinary person – and their choice of images for Instagram posts influence perceptions of the advocates.

II. Literature Review

Environmental activism involves efforts to protect, preserve, and restore the natural environment, tackling issues like climate change, pollution, habitat destruction, and resource depletion (Wolbring & Gill, 2023). Traditional environmental activism faces challenges such as limited resources, political opposition, and public indifference (Hasler et al., 2020). However, social media helps overcome some of these obstacles by inspiring environmental activism through visual messages and promoting sustainable behaviors (Kaur & Chahal, 2018).

Various social media platforms have been instrumental in raising awareness and mobilizing support for environmental causes (Allsop, 2016). For instance, the hashtag #IdleNoMore on Twitter rallied support for indigenous rights and environmental protection (Richez et al., 2020). TikTok videos highlighting sea turtle deaths sparked conversations about water pollution (Hautea et al., 2021). Scientists used Twitter to engage the public in dialogue about the Flint water crisis and mobilize collective action (Jahng & Lee, 2018). Even simple Instagram posts about biking encouraged users to adopt sustainable transportation (McKellar, 2021).

The involvement of young adults in environmental activism on social media is a dynamic and significant phenomenon. Concerns about declining participation in traditional activism among young people have been raised (Gladwell, 2010), with surveys from the early 2000s indicating reduced interest in politics and advocacy (Carpini, 2000). However, recent trends suggest a shift towards “engaged citizenship,” with young adults increasingly integrating activism into daily life (Earl et al., 2017). Challenges persist, including limited environmental education and access to advocacy platforms (Earl et al., 2017). Many movements now view social media as crucial for collaboration, allowing young adults to connect with like-minded peers (Murphy, 2018). Given that young adults aged 18-24 comprise the largest demographic of social media users and are pioneers in using it for environmental activism (Cortes-Ramos et al., 2021; Bisafar et al., 2020), there’s immense potential to engage this group effectively (O’Brien et al., 2018). Understanding how young adults engage with environmental activism on social media is crucial, making 18-24-year-olds the target group for this study.

Instagram as a Platform for Environmental Activism

Instagram serves as a powerful platform for environmental activism among young adults. Its image-centric nature motivates actions and engagement, making it ideal for sharing messages about social and environmental issues (Cortes-Ramos et al., 2021). The platform’s features, such as hashtags and interactive tools like Stories and live videos, facilitate content organization and dynamic interactions (Domingues, 2021). Compared to other social platforms that are discussion-based, Instagram motivates groups of followers to act through image dissemination (Appel et al., 2019).

Environmental activism has found a notable space on Instagram in particular, with advocates using the platform to showcase environmental issues, share conservation tips, and advocate for sustainable practices (Hasler et al., 2020). Instagram has even introduced innovative activist tactics, such as slideshow activism that encapsulates complex issues into a visually compelling and easily shareable format, live activism that uses Instagram’s live streaming feature to broadcast real-time events, protests, and discussions, and hashtag campaigns that uses hashtags to organize causes (Domingues, 2021; Dumitrica et al., 2022; O’Donnell, 2018). These tactics have successfully amplified the reach of environmental causes. To understand how youth respond to visual-based social media posts about environmental advocacy, this study uses Instagram as the target platform.

Advocates as Social Media Influencers

In digital activism, aligning with influencers can boost visibility and impact (Gerbuado, 2017). Influencers, such as celebrities, experts, and grassroots activists, wield significant influence over their followers’ opinions and actions (Leung et al., 2022). They’re recognized for their authenticity, expertise, or charisma, making them effective advocates for social change (Woods, 2016). In the realm of environmental activism, influencers play a crucial role in disseminating messages and mobilizing support (Abidin et al., 2020). Serving as sources of messages about social change, they are also referred to as advocates (Abidin et al., 2020). Anybody can share environmental activism messages on Instagram. However, an advocate’s background, motivation, and past experiences can influence how a message impacts followers’ attitude and behavior toward the advocated issue (Abidin et al., 2020). This study compares the influence of three types of advocates: celebrities, intellectuals, and ordinary individuals.

Celebrities are defined as a well-known individual in entertainment areas like movies, music, writing, or sports (Stewart & Giles, 2020). They leverage their fame to promote environmental causes, though their motives may be questioned by followers (Knoll & Mathes, 2016). Intellectuals, such as scientists and authors, may lack celebrity status but possess expertise that fosters trust among followers (Galetti & Costa-Pereira, 2017). Ordinary individuals could gain popularity through grassroots activism efforts, albeit without prior reputation (Abidin et al., 2020).

Perceptions of Environmental Advocates

When encountering content on social media, individuals form initial impressions based on limited information, shaping perceptions of advocates and activists (Bacev-Giles et al., 2017). The outcome of social activism hinges on how people perceive the advocates and activists involved (Jain et al., 2021). Therefore, this study examines four aspects of perceptions related to authenticity, credibility, homophily, and likability.

Authenticity refers to how genuine an advocate appears in their posts, conveying reliability and dedication (Bailey et al., 2020). In social media context, authenticity is defined as how a post or a picture demonstrates some aspect of the message source’s true self (Pounders et al., 2016). The outcome of social activism is dependent upon the extent to which the public perceives the advocate’s actions as genuine or simply a gimmick (Jain et al., 2021). The three types of advocates to be examined in this project could be perceived of varying levels of authenticity. While celebrities may be the most widely known among the three types, people may question the consistency between their professional persona and activist persona (Knoll & Mathes, 2016). Intellectuals may be perceived more authentic based on their relevant knowledge and expertise on the subject, while ordinary people may be perceived as authentic because they have nothing to lose by participating in environmental social advocacy (Abidin et al., 2020).

Credibility is shaped by factors like expertise and trustworthiness (McCroskey et al., 1974). Different from perceived authenticity, which emphasizes the genuineness and sincerity perceived in an individual or a source of information, perceived credibility focuses on the trustworthiness and reliability attributed to the source of information (Zniva et al., 2023). While intellectuals may be perceived as more credible due to their specialized knowledge in the relevant field (Flanagin et al., 2003), celebrities may rely on their status and visibility. Although ordinary individuals lack specialized knowledge, they may reply on personal experiences or relatability to establish perceptions of crediblity (Flanagin et al., 2003).

Homophily, the tendency to associate with similar individuals, may influence perceived trust and influence (Pereira et al., 2023). Users may connect more with advocates who share their values or experiences, enhancing persuasive influence (Bisgin et al., 2011). Researchers have found that individuals with value-based homophily (i.e., sharing similar beliefs) tended to associate with each other, irrespective of differences in their social status, age, or location, in an online setting (Bisgin et al., 2011). When applied to the context of the current study, if Instagram users perceive a disconnection between the advocate and them regarding values or experiences, the lack of homophily could diminish the persuasive impact, as the users may struggle to relate to or trust the message shared by the advocate (Gupta et al., 2023).

Likability refers to how favorably an individual is perceived based on characteristics or actions (Sleep et al., 2018). Celebrities may garner likability due to fame, intellectuals for expertise, and ordinary persons for relatability (Yeo et al., 2021). In terms of likability by advocate types, celebrities may garner likability due to their fame and charisma, intellectuals for their expertise and authenticity, and ordinary persons for their relatability and authenticity.

Strategic Use of Images on Instagram for Advocacy

In environmental activism on Instagram, advocates strategically use images to shape perceptions and enhance engagement. While photos and videos are common, text-only graphics also play a crucial role, serving as the baseline condition for advocacy posts. Research suggests that images are more effective than words in conveying and enhancing message memorability, known as the picture superiority effect (Li & Xi, 2019). According to the Dual Coding Theory, images facilitate dual encoding verbally and visually, leading to better retention and retrieval of information (Paivio, 2014). Additionally, images evoke stronger emotional responses than text, influencing persuasion and action (Escalas, 2004). For instance, environmental images evoke nostalgic and positive memories of nature, motivating action to protect it (Geise et al., 2020). Images paired with captions reinforce message content, making it more compelling and persuasive (Seo et al., 2013). Effective image use on social media increases activism participation when viewers are appropriately persuaded (Seo, 2020). Therefore, compared to photos featuring environmental events, text-only graphics are less likely to lead to favorable perception and persuasion outcomes.

Research found that images featuring people garnered more likes and engagement compared to textual graphics (Ayres, 2019). This suggests a need for further investigation into how different types of posts and advocates interact to influence perceptions and engagement. However, there is limited literature on the impact of text-only graphic vs. photo on perceptions of the advocate and persuasive intent of advocate message.

Research questions

RQ1. How does advocate type (e.g., celebrity, intellectual, and ordinary person) influence youths’ 1) perceived authenticity, 2) perceived credibility, 3) perceived homophily, and 4) perceived likability of the environmental advocate on Instagram?

RQ2. How do posts with a photo featuring environmental activism event differ from that with a text-only graphic regarding young adults’ 1) perceived authenticity, 2) perceived credibility, 3) perceived homophily, and 4) perceived likability of the environmental advocate on Instagram?

When environmental advocates opt for pictures over text-only graphics, they may employ various persuasive strategies. One such approach is to feature the advocate in the picture, which can enhance perceived authenticity and emotional appeal. Research suggests that the presence of an advocate in a social media post can increase authenticity by signaling dedication and connection to the advocated topic (Appel et al., 2019). Additionally, human presence in messaging can evoke emotions, enhance relatability, and adds realism to the message (Lombard, 1997; Stein et al., 2022). However, the effectiveness of this strategy may depend on factors such as the credibility of the advocate and the audience’s receptiveness to human-centered messages (Lombard, 1997). Based on this discussion, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1. The Instagram post with the advocate’s presence will lead to more perceived authenticity of the advocate compared to the posts without the advocate’s presence.

Aside from exploring the main effects of advocate type and image type, this study also aims to understand how these two factors interact with each other to affect young adults’ perceptions of the advocate.

RQ3. How do advocate type and image type interact with each other to influence young adults’ 1) perceived authenticity, 2) perceived credibility, 3) perceived homophily, and 4) perceived likability of the advocate?

III. Methods

This study employed a 3 (advocate type: celebrity, intellectual, ordinary person) x 3 (image type: a picture featuring an event scene without advocate’s presence, a picture featuring an event scene with advocate’s presence, text-only graphic) between-subjects experiment.

The experiment stimuli included nine fictitious Instagram posts addressing the topic of land pollution. Each fictitious Instagram post was composed of an image, a caption, a source (i.e., the advocate), and a brief biography of the source. The layout of all posts followed the desktop view of an Instagram post for the convenience of manipulation: an image displayed on the left with a source and a caption on the right (Figure 1). All stimulus posts shared the same caption: “Yesterday was National Cleanup Day. I spent a fulfilling day picking up trash and restoring the natural beauty of my local park. Together, we made a difference for our community and the environment. Get involved, lend a hand, and keep our Earth clean and green!” The topic of land pollution was chosen due to its relatively non-controversial nature. While many sustainability issues could evoke debate, land pollution stands out as a universally recognized problem and most people can come to a consensus that littering is harmful. An Instagram bio was added above the caption to disclose the advocate’s background.

Advocate type was manipulated by varying the source of the post. Three types of advocates were examined in this study: celebrity, intellectual, and ordinary person. A pilot test was conducted to determine the appropriate advocate for each type. In this pilot test, each of the ten advocate candidates was shown in an image of a National Cleanup Day event. Other than the featured person, the image was kept the same for all advocate candidates. Each image was accompanied with a brief bio, explaining who the advocate was. Participants were randomly assigned to view these images and were asked to indicate their perceptions of the candidates in terms of fame, reputation, and expertise on environmental issues. Based on the results of the pilot test, we narrowed down to two candidates for each advocate type.

Based on the results of the pilot test, this study narrowed down the celebrity advocate candidates to Matt Damon and Anna Kendrick due to their moderate levels of favor among participants, positioning them in a favorable middle ground. To finalize the choice of celebrity advocate, this study referenced Look to the Stars (https://www.looktothestars.org/), a website that details the advocacy and causes that celebrities are involved with. Based on the information listed on this website, Anna Kendrick was involved with fewer environmental and sustainability causes than Matt Damon, which could rule out the possibilities for participants to overly associate her as being a well-known advocate for a certain cause. She was therefore chosen as the final candidate for celebrity advocate.

To finalize the choice of celebrity advocate, this study referenced the Look to the Stars website (https://www.looktothestars.org/), which lists the advocacies and causes celebrities are involved in and chose Anna Kendrick as the celebrity advocate for this study. Kendrick is moderately involved in environmental and sustainability issues and is not strongly associated with any single cause. Her bio reads “Actress, Musical Enthusiast, Comedian (kind of).” To minimize the potential gender effect, the study decided to adopt the same gender for the other two types of advocates. For the intellectual advocate, this study chose a fictitious figure named Christina Archer with a bio that reads, “Professor of Environmental Science at University of Delaware, Researching Environmental Ethics.” For the ordinary person advocate, this study created another fictitious figure named Alexandra Mitchell with a bio that reads, “Coffee Lover, Movie Enthusiast, Dog Mom.”

The images included in the fictitious Instagram posts had three types: a photo featuring a National Cleanup Day event with the advocate’s presence, a photo featuring the same event without the advocate’s presence, and one text-only graphic without featuring either the event or the advocate. In the condition featuring the event scene with the advocate’s presence (Figure 1), the image depicted the advocate in the foreground of a photo in a park, smiling and holding a full bag of litter. The advocate was wearing a t-shirt and rubber gloves. There are others in the background, wearing matching t-shirts and picking up litter in the park. To minimize any confounding effect, AI face-swap technology and Photoshop were used to ensure the consistency among different types of advocates shown in the advocate-present conditions. They were displayed as having the same outfit and gestures with very similar facial expressions (See Figure 2).

In the condition featuring the event scene without the advocate’s presence (Figure 2), the image showed a group of people participating in the cleanup event in the middle ground and background. None of the faces was recognizable, and all the subjects were shown picking up litter in the park. They were all wearing the matching green t-shirts. No advocate was featured in this picture.

The text-only graphic condition serves as the baseline condition for this study (Figure 3). This condition featured a text-only graphic generated via the Instagram’s Create Mode. It was of the same size as the other two images and only contained the text “National Cleanup Day” written in a black font and overlaid on top of an image of a forest, matching the scene depicted in the other two conditions.

Participants

A total of 155 undergraduate students participated in this experiment. Among them, there were more first-year (26.5%) and sophomore (27.7%) students than junior (16.1%) and senior (25.2%) students. The others did not indicate their academic standing. More than half of the participants were female (55.5%) with 36.8% as male, 2.6 % as non-binary/third gender, and 0.6% preferring not to disclose their gender. The majority of participants identified their race as white (70.3%), while 8.3% identified as Asian, 7.7% as Black or African American, and 2.6% as Hispanic or Latinx. The others were either multiracial (4.5%) or chose not to indicate their race (1.3%). The average age of participants was 19.70 years old, SD =1.32.

After indicating their consent to participation. participants first answered questions about their prior involvement in environmental advocacy on Qualtrics and were then randomly assigned to view one of the nine fictitious Instagram posts. After that, they completed an online questionnaire about perceptions of the post of the advocate type, as well as attitudes and behavioral intentions toward land pollution to ensure the manipulation was effective and recognized. Upon completion of the questionnaire, they were offered the option to enter a random drawing to win an Amazon gift card by clicking a separate link to provide their email.

Dependent Variables

Perceived authenticity of the advocate was measured by six items adapted from Zniva et al. (2023) on a 7-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88, M = 4.65, SD = 1.25). These items were “This person has a true passion for the advocated cause”; “This person does his/her best to share his/her experiences”; “This person loves what he/she is doing”; “This person is genuine”; “This person is real to me”; and “This person is authentic.”

Perceived credibility of the advocate was measured by eight items adapted from Gass and Seiter (2022) and McCroskey et al. (1974) on a 7-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94, M = 4.11, SD = 1.36). They were “This person is credible”; “This person is believable”; “This person is reliable”; “This person is trustworthy”; “This person is authoritative”; “This person is reputable”; “This person is knowledgeable about the advocated issue”; and “This person is of expertise on the advocated issue.”

Perceived homophily towards the advocate was measured by four items adapted from Pereira et al. (2023) on a 7-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89, M = 3.67, SD = 1.18). These items included “This person and I have a lot in common”; “This person and I are a lot alike”; “This person thinks like me”; and “This person shares my values”.

Perceived likability of the advocate was measured by four items adapted from Yeo et al. (2021) on a 7-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.95, M = 5.21, SD = 1.20). These items were “This person seems friendly”; “This person seems likable”; “This person seems warm”; and “This person seems approachable.”

Prior involvement with environment advocacy was included as the control variable in this study. It included four items adapted from Moore et al. (2014) and measured on a 7-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.74, M = 4.29, SD = 1.35). These items included “I have donated to causes related to sustainability before”; “I have taken action towards sustainability before”; “I have thought about land pollution as an issue before”; and “I have performed research on land pollution before.”

IV. Data Analysis and Results

Two-way factorial analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) with prior involvement with environment advocacy as the control variable were used to explore the main and interaction effects of advocate type and image type on perceptions of the advocate.

Effects on Perceived Authenticity of the Advocate

There was a significant main effect of image type on perceived authenticity of the advocate, F (2, 146) = 28.36, p < .01. The post-hoc test showed that the advocate was perceived significantly less authentic in the text-only graphic condition (M = 3.74, SE = .15) than in both the condition featuring the event scene without the advocate’s presence (M = 5.13, SE = .15) and the condition featuring the event scene with the advocate’s presence (M = 4.99, SE = .14). There was no significant difference between the condition featuring the event scene without the advocate’s presence and the condition featuring the event scene with the advocate’s presence, which undermined H1.

There was also a significant main effect of advocate type on perceived authenticity, F (2, 145) = 8.31, p < .01. The post hoc test indicated that the intellectual (M = 5.10, SE = .14) was perceived significantly more authentic than both the ordinary person (M = 4.33, SE = .15) and the celebrity (M = 4.43, SE = .15). There was no significant difference between the ordinary person and the celebrity regarding perceived authenticity. There was also no significant interaction effect between advocate type and image type on perceived authenticity.

Effects on Perceived Credibility of the Advocate

The analysis revealed a significant main effect of image type on perceived credibility of the advocate, F (2, 143) = 7.78, p < .01. The post hoc test showed that the advocate was perceived significantly less credible in the text-only graphic condition (M = 3.54, SE = .17) than in both the condition featuring the event scene without the advocate’s presence (M = 4.33, SE = .16) and the condition featuring the event scene with the advocate’s presence (M = 4.37, SE = .16). There was no significant difference between the condition featuring the event scene without the advocate presence and the condition featuring the event scene with the advocate presence regarding perceived credibility.

There was also a significant main effect of advocate type on perceived credibility, F (2, 143) = 25.65, p < .01. The post hoc tests revealed that the intellectual (M = 4.95, SE = .16) was perceived significantly more credible than both the celebrity (M = 3.94, SE = .16) and the ordinary person (M = 3.36, SE = .16). The celebrity was also perceived as significantly more credible than the ordinary person. No significant interaction effect between advocate type and image type was found on perceived credibility.

Effects on Perceived Homophily of the Advocate

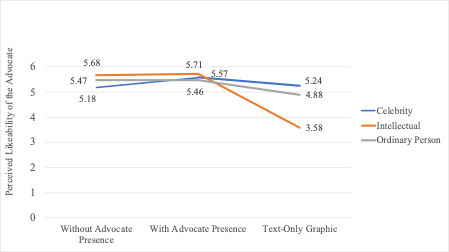

For perceived homophily of the advocate, this study discovered a significant main effect of image type, F (2, 141) = 4.01, p < .05. The post-hoc test showed that the text-only graphic condition (M = 3.31, SE = .15) led to significantly less perceived homophily of the advocate than both the condition featuring the event scene without the advocate’s presence (M = 3.89, SE = .15) and the condition featuring the event scene with the advocate’s presence (M = 3.75, SE = .14). There was no significant difference between the conditions featuring the event scene with and without the advocate’s presence. There was also a significant interaction effect of advocate type and image type on perceived homophily, F (4, 141) = 4.35, p < 0.01. When the advocate was either a celebrity or an intellectual, using text-only graphic led to less perception of homophily toward the advocate than when the advocate was an ordinary person. When the photo featuring the event scene with or without the advocate’s presence was used, the advocate type did not matter at all regarding perceived homophily of the advocate. Figure 4 provides an illustration of this interaction effect. No significant main effect was found for advocate type.

Effects on Perceived Likability of the Advocate

For perceived likability of the advocate, there was a significant main effect of image type on perceived likability, F (2, 141) = 12.80, p < .01. The post-hoc test showed that the advocate was perceived less likeable in the text-only graphic condition (M = 4.57, SE = .15) than in both the condition featuring the event scene without the advocate’s presence (M = 5.44, SE = .15) and the condition featuring the event scene with the advocate’s presence (M = 5.58, SE = .14). There was no significant difference between the condition featuring the event scene without the advocate’s presence and the condition featuring the event scene with the advocate’s presence.

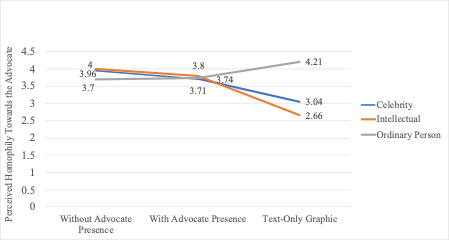

There was also a significant interaction effect between advocate type and image type on perceived likability of the advocate, F (4, 141) = 5.65, p < .01. When the text-only graphic was used, the intellectual was perceived significantly less likable than both the celebrity and the ordinary person. However, when the picture featuring the event scene with or without the advocate’s presence was used, the advocate type did not matter at all in terms of perceived likability of the advocate (See Figure 5). No significant main effect was found for advocate type regarding perceived likability.

V. Discussion & Conclusion

The results of this study shed light on the effects of advocate type and image type on people’s perceptions of the advocates. The implications of these findings and their relevance to understanding digital activism strategies on Instagram are discussed below.

Key Findings and Implications

Perceived Authenticity and Credibility. The findings suggest that both advocate type and image type play crucial roles in shaping perceptions of authenticity and credibility. Text-only graphics led to lower perceptions of authenticity and credibility of the advocate compared to the images featuring event scenes, regardless of the presence of the advocate. This indicates the importance of visual elements in enhancing perceived authenticity and credibility of the advocate. If audiences perceive the advocate as authentic, the outcome of the activism message is likely more effective (Jain et al., 2021). Furthermore, the intellectual was perceived as significantly more authentic and credible than both the celebrity and the ordinary person, with the celebrity perceived as more credible than the ordinary person. This result indicates that the advocate’s Instagram biography could influence perceived authenticity and credibility, since the intellectual lists environmental contributions and achievements whereas the other does not. The celebrity advocate may have been perceived as more authentic than the ordinary-person advocate due to professional achievements listed in the Instagram biography, as well as participants’ recognition of the celebrity. This emphasizes the particular importance of expertise and knowledge in establishing credibility in environmental activism efforts. Advocates should use and leverage the image type to enhance perceived authenticity and credibility, thereby increasing the effectiveness of activism messages.

Perceived Homophily and Likability. The study highlights the impact of image type on perceptions of homophily and likability toward the advocate. Text-only graphics led to lower perceptions of homophily and likability compared to images featuring event scenes, likely due to the sense of connection and relatability generated by visual messaging. Interestingly, the text-only condition increased perceptions of homophily with the ordinary person advocate, possibly due to heightened relatability, as participants may project themselves onto the message, fostering a stronger connection. Advocate type influenced perceived likability in the text-only graphic condition, but this effect diminished when any event scene image was used, suggesting that real photos of events demonstrate dedication and foster a sense of connection and approachability. Conversely, text-only graphics may lead participants to perceive the advocate as disconnected, damaging perceived likability. This aligns with previous findings showing a positive correlation between perceived likability and approachability (Yeo et al., 2021).

The interaction effects between advocate type and image type on perceptions of homophily and likability were observed suggests that the text-only graphics provide a more straightforward way to for followers to evaluate the advocate’s likability. Additionally, the significant influence of advocate type on perceptions of homophily in the text-only graphic condition implies that textual content may make the differences between advocates more noticeably.

Implications for Digital Environmental Activism. These findings underscore the importance of strategic digital activism on Instagram, particularly in leveraging visually engaging content to enhance advocacy efforts. Advocates should prioritize using images depicting conservation efforts, volunteer events, or community initiatives in action, which can boost perceptions of authenticity, credibility, homophily, and likability (Dumitrica et al., 2022). With the information overload on social media, different posts are competing for users’ attention. Therefore, digital environmental advocates should develop strategies to capture and maintain their audiences’ attention. Aside from prioritizing visually engaging content, they may also consider using Instagram’s slideshow feature, which can provide a more in-depth exploration of environmental issues, allowing advocates to capture and maintain their audience’s attention for longer periods (Dumitrica et al., 2022). By adopting these strategies, digital environmental advocates can effectively engage their audiences and inspire collective action for positive environmental change on social media.

Limitations and Future Directions

It is essential to acknowledge some limitations of this study, such as the focus on a specific age group (young adults) and specific environmental issue (land pollution), which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Future research could explore the effects of advocate type and image type across different demographic groups and a broader range of environmental concerns. Additionally, longitudinal studies could assess the long-term effects of social media activism campaigns, rather than singular posts, providing valuable insights for sustainable behavior change efforts.

The study relied on self-reported measures to capture perceptions of the advocate, which is subject to social desirability biases and may not fully capture participants’ true perceptions. Employing additional approaches, such as combining the survey with qualitative interviews or observational studies, could provide a more comprehensive understanding of participants’ responses to activism messages on Instagram.

Our study focused exclusively on Instagram as the social media platform for digital activism. However, different social media platforms may have unique features that influence the effectiveness of activism strategies. Future research could compare the influence of activism messages across multiple platforms (e.g., X, Facebook, and TikTok) and examine how platform-specific features shape audience responses to environmental activism efforts.

This study highlights how different types of advocates and their choice of image affect how people perceive environmental advocates and activists on Instagram. It shows that using pictures, especially those depicting environmental conservation events, can enhance perceived authenticity, credibility, homophily, and likability of the advocate. Advocates, regardless of their identity, stand to benefit significantly from leveraging visual storytelling to increase the impact of their activism efforts. By tapping into the power of imagery, advocates can forge deeper connections with their audiences, foster trust, as well as inspire action and favorable attitudes toward helping environmental causes.

This study offers valuable insights into the evolving landscape of digital environmental activism, guiding advocates, organizations, and researchers toward more impactful strategies for effecting positive change in our world. By harnessing the collective power of visual storytelling and advocate engagement, we can foster a more sustainable future for generations to come.

Acknowledgements

I would like to sincerely thank my research mentor, Dr. Qian Xu, for the incredible efforts she put in to helping my shape my research into what it is today. I could not have done this without you! I would also like to thank all of the professors I have had during my time at Elon for inspiring me to go after my passions and to think critically.

References

Abidin, C., Brockington, D., Goodman, M. K., Mostafanezhad, M., & Richey, L. A. (2020). The tropes of celebrity environmentalism. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 45(1), 387–410. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-012320-081703

Allsop, B. (2016). Social media and activism: A literature review. Social Psychological Review, 8(2), 35-40.

Appel, G., Grewal, L., Hadi, R., & Stephen, A. T. (2019). The future of social media in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(1), 79–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-019-00695-1

Ayres, S. (2019). Do Instagram users like graphics or photos? Social Media Lab. https://www.agorapulse.com/social-media-lab/instagram-graphics-photos-engagement/

Bacev-Giles, C., & Haji, R. (2017). Online first impressions: Person perception in social media profiles. Computers in Human Behavior, 75, 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.04.056

Bailey, E. R., Matz, S. C., Wu, Y., & Iyengar, S. S. (2020). Authentic self-expression on social media is associated with greater subjective well-being. Nature Communications, 11(1), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18539-w

Bisafar, F., Foucault Welles, B., D’Ignazio, C., & Parker, A. G. (2020). Supporting youth activists’ strategic use of social media. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 4 (CSCW2), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1145/3415180

Bisgin, H., Agarwal, N. & Xu, X. A study of homophily on social media. World Wide Web, 15, 213–232 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11280-011-0143-3

Carpini, M. X. (2000). Gen.com: Youth, civic engagement, and the new information environment. Political Communication, 17, 341–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600050178942

Cortés-Ramos, A., Torrecilla García, J. A., Landa-Blanco, M., Poleo Gutiérrez, F. J., & Castilla Mesa, M. T. (2021). Activism and social media: Youth participation and communication. Sustainability, 13(18), 10485. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810485

Domingues, Y. (2021). Brand activism in social media: The impact of brand activism content on Instagram engagement [Master’s thesis, Universidade Católica Portuguesa].

Dumitrica, D., & Hockin-Boyers, H. (2023). Slideshow activism on Instagram: Constructing the political activist subject. Information, Communication & Society, 26(16), 3318-3336. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2022.2155487

Earl, J., Copeland, L., & Bimber, B. (2017). Routing around organizations: Self-directed political consumption. Mobilization: An International Quarterly, 22(2), 131-153.

Escalas, J. E. (2004). Imagine yourself in the product: Mental simulation, narrative transportation, and persuasion. Journal of Advertising, 33(2), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2004.10639163

Galetti, M., & Costa-Pereira, R. (2017). Scientists need social media influencers. Science, 357(6354), 880–881. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao1990

Gass, R. H., & Seiter, J. S. (2022). Persuasion: Social influence and compliance gaining. Routledge.

Geise, S., Panke, D., & Heck, A. (2020). Still images—moving people? How media images of protest issues and movements influence participatory intentions. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 26(1), 92–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220968534

Gerbaudo, P. (2017). From cyber-autonomism to cyber-populism: An ideological history of digital activism. Triple C: Communication, Capitalism & Critique, 15(2), 478–491.

Gladwell, M. (2010, October 4). Small change: Why the revolution will not be tweeted. New Yorker. Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/10/04/small-change-malcolm-gladwell

Gupta, P., Burton, J. L., & Costa Barros, L. (2023). Gender of the online influencer and follower: The differential persuasive impact of homophily, attractiveness, and product-match. Internet Research, 33(2), 720-740. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-04-2021-0229

Hasler, O., Walters, R., & White, R. (2020). In and against the state: The dynamics of environmental activism. Critical Criminology, 28, 517–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10612-019-09432-0

Hautea, S., Parks, P., Takahashi, B., & Zeng, J. (2021). Showing they care (or don’t): Affective publics and ambivalent climate activism on TikTok. Social Media and Society, 7(2), 20563051211012344.

Herrmann, C., Rhein, S., & Dorsch, I. (2023). #fridaysforfuture – What does Instagram tell us about a social movement? Journal of Information Science, 49(6), 1570-1586. https://doi.org/10.1177/01655515211063620

Hong, H., & Kim, Y. (2021). What makes people engage in civic activism on social media? Online Information Review, 45(3), 562-576. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-03-2020-0105

Jahng, M. R., & Lee, N. (2018). When scientists tweet for social changes: Dialogic communication and collective mobilization strategies by Flint water study scientists on Twitter. Science Communication, 40(1), 89–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547017751948

Jain, K., Sharma, I., & Behl, A. (2021). Voice of the stars – exploring the outcomes of online celebrity activism. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254x.2021.2006275

Jain, R., Kelly, C. A., Mehta, S., Tolliver, D., Stewart, A., & Perdomo, J. (2021). A trainee-led social media advocacy campaign to address COVID-19 inequities. Pediatrics, 147(3). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-028456

Kaur, A., & Chahal, H. S. (2018). Role of social media in increasing environmental issue awareness. Researchers World, 9(1), 19-27. https://doi.org/10.18843/rwjasc/v9i1/03

Knoll, J., & Matthes, J. (2016). The effectiveness of celebrity endorsements: A meta-analysis. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(1), 55–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-016-0503-8

Leung, F. F., Gu, F. F., & Palmatier, R. W. (2022). Online influencer marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 50, 226–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-021-00829-4

Li, Y., & Xie, Y. (2019). Is a picture worth a thousand words? An empirical study of image content and social media engagement. Journal of Marketing Research, 57(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022243719881113

Lombard, M., & Ditton, T. (1997). At the heart of it all: The concept of presence. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.1997.tb00072.x

McCroskey, J. C., Hamilton, P. R., & Weiner, A. N. (1974). The effect of interaction behavior on source credibility, homophily, and interpersonal attraction. Human Communication Research, 1(1), 42-52.

McKellar, E. (2021). Shopping for a cause: Social influencers, performative allyship, and the commodification of activism [Master’s thesis, California State University, San Bernardino]. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/1377

Moore, E., Warta, S., & Erichsen, K. (2014). College students’ volunteering: Factors related to current volunteering, volunteer settings, and motives for volunteering. College Student Journal, 48(3), 386-396.

O’Brien, K., Selboe, E., & Hayward, B. M. (2018). Exploring youth activism on climate change: dutiful, disruptive, and dangerous dissent. Ecology and Society, 23(3): 42. https://doi.org/10.5751/es-10287-230342

O’Donnell, N. (2018). Storied lives on Instagram: Factors associated with the need for personal-visual identity. Visual Communication Quarterly, 25(3), 131-142. https://doi.org/10.1080/15551393.2018.1490186

Paivio, A. (2014). Intelligence, dual coding theory, and the brain. Intelligence, 47, 141–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2014.09.002

Pounders, K., Kowalczyk, C. M., & Stowers, K. (2016). Insight into the motivation of selfie postings: Impression management and self-esteem. European Journal of Marketing, 50(9/10), 1879-1892.

Richez, E., Raynauld, V., Agi, A., & Kartolo, A. B. (2020). Unpacking the political effects of social movements with a strong digital component: The case of #IdleNoMore in Canada. Social Media+Society, 6(2), https://doi.org/10.1177/205630512091558

Seo, K. (2020). Meta-analysis on visual persuasion– does adding images to texts influence persuasion? Athens Journal of Mass Media and Communications, 6(3), 177–190. https://doi.org/10.30958/ajmmc.6-3-3

Seo, K., Dillard, J. P., & Shen, F. (2013). The effects of message framing and visual image on persuasion. Communication Quarterly, 61(5), 564-583. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463373.2013.822403

Sleep, C. E., Hyatt, C. S., Lamkin, J., Maples-Keller, J. L., & Miller, J. D. (2018). Examining the relations among the DSM–5 alternative model of personality, the five-factor model, and externalizing and internalizing behavior. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 9(4), 379.

Stein, J. P., Linda Breves, P., & Anders, N. (2022). Parasocial interactions with real and virtual influencers: The role of perceived similarity and human-likeness. New Media & Society, 26(6), 3433-3453. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221102900

Stewart, S., & Giles, D. (2019). Celebrity status and the attribution of value. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 23(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549419861618

University of Sussex (2023). Is digital media effective? Retrieved from https://study-online.sussex.ac.uk/news-and-events/social-media-and-campaigning-is-digital-activism-effective/

Wolbring, G., & Gill, S. (2023). Potential impact of environmental activism: A survey and a scoping review. Sustainability, 15(4), 2962. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15042962

Woods, S. (2016). #Sponsored: The emergence of influencer marketing [Undergraduate honors thesis, University of Tennessee]. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/1976

Yeo, S. K., Cacciatore, M. A., Su, L. Y. F., McKasy, M., & O’Neill, L. (2021). Following science on social media: The effects of humor and source likability. Public Understanding of Science, 30(5), 552-569. https://doi.org/10.1177/096366252098694

Yuen, S., & Tang, G. (2023). Instagram and social capital: Youth activism in a networked movement. Social Movement Studies, 22(5-6), 706-727. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2021.2011189

Zniva, R., Weitzl, W. J., & Lindmoser, C. (2023). Be constantly different! How to manage influencer authenticity. Electronic Commerce Research, 23(3), 1485-1514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10660-022-09653-6

Figure 1. The Post for the Celebrity as Advocate + Advocate Presence Condition

Figure 2. Pictures Featuring the Event Scene with and Without the Advocate’s Presence

Note. Top left: Anna Kendrick as the celebrity advocate; Top right: Christina Archer as the intellectual advocate; Bottom left: Alexandra Mitchell as the ordinary person advocate; Bottom right: the advocate absent condition.

Figure 3. The Post for the Text-Only Graphic Condition

Figure 4. Interaction Effect of Advocate Type and Image Type on Perceived Homophily of the Advocate

Figure 5. Interaction Effect of Advocate Type and Image Type on Perceived Likability Towards the Advocate