- Home

- Academics

- Communications

- The Elon Journal

- Full Archive

- Fall 2024

- Fall 2024: Matt Newberry

Fall 2024: Matt Newberry

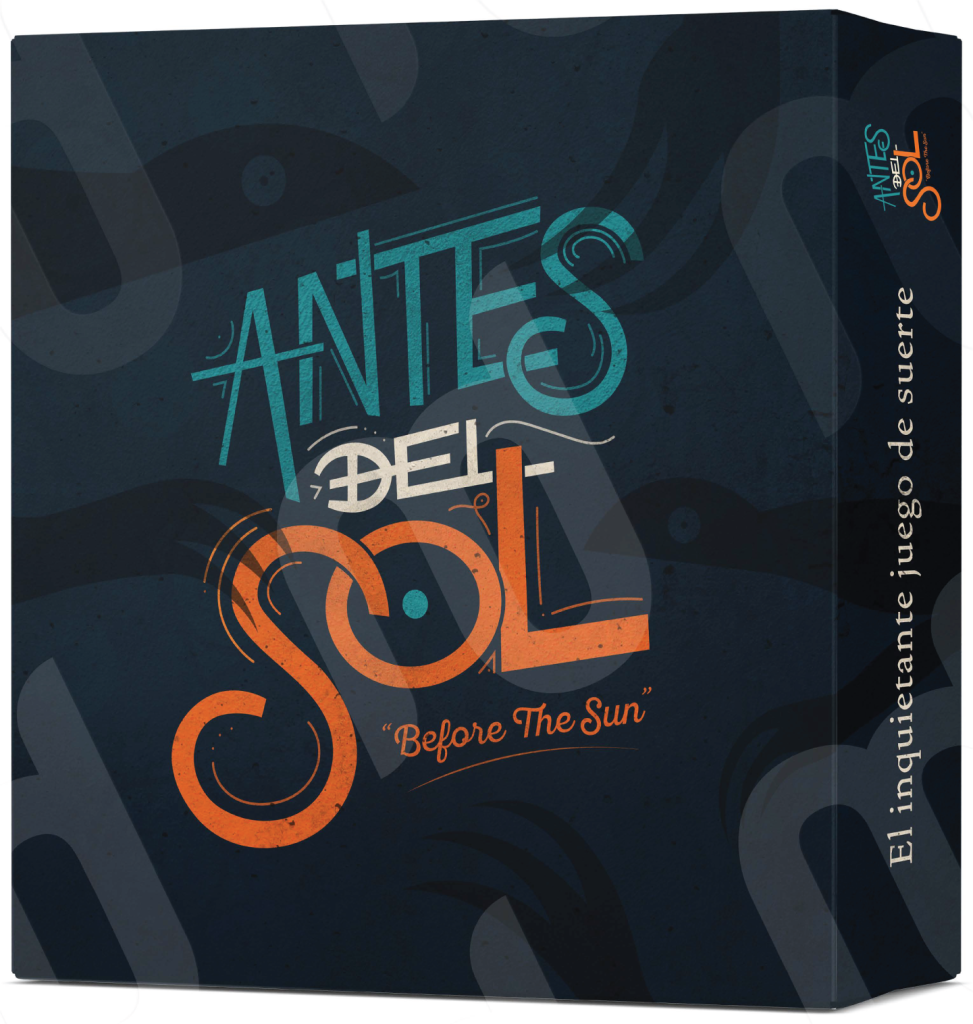

Antes del sol (Before the Sun): Bridging Acculturation Gaps in Hispanic and Latin American Immigrant Families with a Dual-Language Board Game

Matt Newberry

Communication Design, Elon University

Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements in an undergraduate senior capstone course in communications

Abstract

A breadth of past research has identified a pattern of conflict that typically arises in Hispanic and Latin American immigrant families in the United States due to acculturation gaps and linguistic differences caused by Shared Language Erosion. In a distinct, three-generation cycle, the heritage language can be lost within a family as descendants assimilate into their host culture after just a few decades. As a result, strained communication and discrepancies in cultural perspectives tend to ignite frustration, anger, and resentment among family members. In an effort to resolve these issues of separation among parents, grandparents, and children that result from declining heritage language proficiencies, this project investigates the role of board games for educational development in linguistic competency and how they may act as vehicles for interpersonal communication and bonding. Furthermore, the research identifies strategies for second language acquisition through quality time and leisure activities with native speakers of one’s second language. The creative element consists of an excitingly “haunting” dual-language board game called Antes del sol. The game features classic game pieces like cards, tokens, and pawns, but it also utilizes a mobile companion app to facilitate gameplay. Additional promotional and branding materials were also developed to enhance and advertise the project. Ideally, the game will function as an opportunity for family members to connect through gameplay while also helping them become more proficient in the language less comfortable to them. This outcome allows for the project to have additional uses in classroom settings, as well as expansion opportunities for future editions with additional languages or dialects.

Keywords: immigration, family, board games, language, design

Email: mnewberry@elon.edu

Terminology Note: As conversations about inclusive language for Spanish-speaking people remain unsettled, individuals who identify as being of Latin American descent will be referred to as “Latin American-identifying,” “Latin people,” or “Latines” for the purposes of this research. Latin is the English word used to describe Latin American culture, i.e. Latin music, Latin food, Latin design. The term “Latine” is meant to be a gender-inclusive alternative to Latino or Latina that has more favorability among Spanish-speaking groups than the recently popularized term, Latinx (“Latine vs. Latinx,” 2021). Gender-inclusive language is not yet a concept adopted by the Spanish-speaking world at large, but those who use it argue that Latine is more consistent with the Spanish language than Latinx (McGee, 2022). This decision was also made due to research showing that only 3% of Latin American individuals even use Latinx, and 76% of those surveyed had never even heard the word (Noe-Bustamante et al., 2020).

I. Introduction

Fights without resolution. Misunderstandings without communication. Families without connection. There is a common phenomenon among immigrant families in which conflicts arise as communication and cultural similarities become strained. This problem is linked to a “universal preference for and mastery of English across minority populations, as well as rapid loss of heritage language across immigrant generations” (Wang et al., 2022). Heritage cultures disappear through the United States immigration process in a distinct, three-generation cycle (Alba et al., 2002). Typically, the first generation learns enough English to survive economically and do business in the host country, and the second generation becomes bilingual by speaking their heritage language (HL) at home while speaking English everywhere else (Portes & Shauffler, 1994). The third generation typically speaks English at home with little knowledge of their HL, thus impeding them from passing it on to future generations (Portes & Shauffler, 1994). This pattern typically leads to familial conflict because (grand)parents might be angry with their children for not speaking their HL (Verhaeghe et al., 2022). However, the children might be angry in return because the (grand)parents do not want to speak the host culture language with them. They may also feel resentment because their (grand)parents did not speak their HL enough during childhood to allow for a greater proficiency and connection to their heritage culture (Verhaeghe et al., 2022). This common problem has been linked to dissonance caused by acculturation and Shared Language Erosion, which can both potentially be resolved due to the educational and communicative benefits of board gameplay (Cox et al., 2021). Board games are known to have a plethora of cognitive benefits for toddlers and senior citizens alike. They drive interpersonal communication and familial connection through leisure, which is also a key component for the successful acquisition of second languages. In foreign language learning, teachers often emphasize the importance of practice outside of the classroom. Extracurricular activities are very useful ways of expanding one’s knowledge of a new language, especially when they are exposed to a native speaker of their second language (Zakhir, 2019). Additionally, someone learning a second language separately from formal classroom instruction typically gains a more developed competency in their second language because they have a stronger motivation to enhance their understanding and production of it (Hernández, 2010). This vast collection of research on language, relationships, education, and board games support this project’s creation of a dual-language board game that can serve as a basis for connection among disconnected members of Hispanic and Latin American immigrant families in the United States.

II. Disconnections between Heritage Cultures and Host Cultures

Acculturation

For many immigrant families, acculturation gaps form as people move to a different country and their descendants have the new host culture to call home. These gaps typically cause intergenerational conflict because communication and cultural similarities between grandparents, parents, and children are all hindered as the heritage culture gradually fades away. While both parents and children can be culturally in sync through this familial transition, the issues discussed in this research are more pronounced with generations born into the host culture without first-hand experience in their heritage culture and HL (Nesteruk, 2022).

The quick assimilation process known as dissonant acculturation is most prevalent among Latin immigrants in the United States, and it occurs when children adjust to the host culture much faster than older generations (Nesteruk, 2022). If the children are actively involved in social activities and schooling, they can become proficient in the host language within a couple of years (Birman & Poff, 2011). When this phenomenon occurs, conflict between adolescents and their parents tend to be more distinct. By enforcing conservative or strict beliefs from their heritage culture that may not match the typical parenting styles of the host culture, children may “resent strict parenting styles when they see their peers’ parents practice more permissive parenting” (Birman & Poff, 2011). Additionally, children may find themselves frustrated through cultural brokering, a process in which they must explain cultural nuances to their (grand)parents. For example, they may find themselves “having to ask parents to lower their voice in public, be less direct, and less confrontational in interaction with ‘the Americans’” (Nesteruk, 2022). They may also become more open-minded and accepting of progressive views on topics like same-sex relationships, and children can find themselves challenging their parents’ racist, homophobic, transphobic, or sexist perspectives (Nesteruk, 2022). This intergenerational dissonance has been linked to problems such as depression, poor academic achievement, and a higher likelihood for an adolescent to partake in delinquent behaviors. Alcohol and tobacco use is particularly common for Mexican American adolescents experiencing acculturation differences with their parents (Birman & Poff, 2011).

Shared Language Erosion (SLE)

The primary factor that determines acculturation in immigrant families is language. While there has been a substantial increase in the number of dual-language households in the United States over the past three decades, it is still infamously “described as a ‘graveyard’ for languages” (Cox et al., 2021). It feels very ideological in the sense that, “to be American, one must speak English” (Verhaeghe et al., 2022) Thus, by the time someone becomes proficient in speaking English, they have likely assimilated into every other aspect of American culture. The prevalent cycle of heritage language (HL) loss is known as Shared Language Erosion (SLE), and this pattern consistently occurs very distinctly after three generations — a point where the third-generation immigrant children have limited knowledge of their HL or none at all. Almost half of Latin immigrant adolescents in the United States report “high levels of misunderstanding in their communication with their parents due to navigating two languages at home” (Cox et al., 2021) These statistics display the effect of how SLE can render parents and children unable to communicate successfully and effectively. This phenomenon causes differences in beliefs, morals, values, and behaviors between generations that further explain documented mental and physical health problems among immigrant youth.

Loss of the HL also creates conflict through language brokering: a process in which children must translate documents and interpret verbal communication in various settings for their immigrant (grand)parents (Nesteruk, 2022). Essentially, the second generation often takes on the role of the “translator” within the family and in public (Verhaeghe et al., 2022). They also become the “narrator” by giving contextual information as they translate for their family members, the “director” by structuring the dialogue they are translating and deciding who gets to speak, and the “broker” by making arrangements for when any of these discussions will take place and monitoring what is shared in the conversation (Verhaeghe et al., 2022). These common practices can lead to stress, frustration, aggravation, embarrassment, and resentment on behalf of the child as they find themself responsible for keeping up with the details and business of adulthood that usually fall under the duties of the parent (Nesteruk, 2022).

It is also important to note that studies have found that parent-adolescent relationships are strained due to the degree of HL proficiency rather than whether they speak it at all. In other words, conflict arises between family members unless the child can very closely match the HL proficiency of their parent(s), which is not usually possible unless the child is also receiving some sort of formal instruction in their HL outside of the home to prevent monolingualism (Cox et al., 2021). This exception is still not guaranteed. A study comparing the language use of immigrant students at a bilingual private school and public school in Florida found that over 70 percent of the Latin students reported knowing English very well in both scenarios. The types of schooling resulted in minimal differences between the two groups studied, and “only age, national origin and length of United States residence are significantly related to English proficiency” (Portes & Shauffler, 1994). Additionally, 80 percent of the entire sample studied also demonstrated an overwhelming preference for speaking English (Portes & Shauffler, 1994). With a predicted influx of immigrant populations in the United States over the next 50 years, there will hopefully be a stronger presence of global influence in the country with a greater prevalence of bilingualism.

III. Benefits of Board Gameplay

Emotional Effects & Self-Expression

Research establishes that board games are very effective vehicles for driving connection and bonding within families, and they also have many educational benefits. They have been enjoyed by people around the world since 5,000 B.C.E., and games still prove to be a key component in building familial communication and respect throughout childhood (Brunscheen-Cartagena et al., 2019). Board games also promote love and a sense of belonging through intergenerational play, which are two qualities listed in Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Thus, games can significantly impact the quality of life for a child, especially as they develop soft skills, learn how to read body language, and practice communicating from a young age (Brunscheen-Cartagena et al., 2019).

One study with first-grade children found that board games allowed children to “express themselves through all of their available expressive, communicative, and cognitive languages” (Collins et al., 2011). Even for a young Latin child who experienced a language barrier with his Caucasian classmate, a board game taught both children to communicate more effectively with each other and apply those new skills in their later conversations away from the game (Collins et al., 2011).

Educational & Intellectual Effects

Board games have been used in classrooms for educational purposes as well. By creating an enjoyable atmosphere for learning new information, board games have proven to be beneficial in intellectual retention and positive student sentiment. This form of gamified learning was used for a study involving nursing students in Taiwan. With the knowledge that more than 60 percent of university students still enjoy playing board games in their free time, the study aimed to determine whether nursing students could learn about medication more effectively through a board game than traditional lecture (Chang et al., 2022). While there were no differences between the two groups according to exam results, the experimental group was able to recall significantly more information one month later. Thus, board games can be assumed to have “a higher potential for the transfer of learned content from short-term memory to long-term memory” (Chang et al., 2022). The students who participated in gamified learning also reported that they favored the experimental learning method much more than traditional lectures. In simpler terms, they had fun while they were learning (Chang et al., 2022). These benefits are crucial for those attempting to learn a new language and maintain their proficiency for a long time.

Furthermore, board games have been used to enhance students’ knowledge and awareness of environmental topics. One study found that games encouraged social interactions and discussions between players while also drawing them closer to the educational content through play (Fjællingsdal & Klöckner, 2020). Board games are also effective stimulants for older adults because they can boost collaboration, creativity, patience, strategic thinking, and problem-solving skills (Brunscheen-Cartagena et al., 2019). Therefore, the benefits of using interactive methods for mastering educational concepts and encouraging communicative relationships between players have been strongly associated with positive outcomes that could be applicable for resolving the problems and conflicts that commonly arise in the households of Hispanic and Latin American immigrant families in the United States.

IV. Strategies for Second Language Acquisition (SLA)

Cognitive Evidence of SLA through Social Interaction

A 2019 study examined SLA through the lens of social interaction. Using behavioral and brain data, researchers found that the majority of adult second language (L2) learners rely on translation or an association of two languages — in addition to repetition memory. This form of cognitive language processing is unlike a child who typically learns the first language (L1) through sensorimotor experiences in a perceptually enriched environment. These vocabulary and grammar associations commonly used by adult L2 learners often leads to “parasitic lexical representation,” meaning a word in the L2 is linked to a conceptual system already established in the L1 (Li & Jeong, 2019). Because the word’s association or translation does not have a direct relationship between the L2 and the concept, the link of the L2 word to the concept is much weaker for an adult than a child. The study also used brain imaging data to suggest that socially learning L2 against individual learning in the classroom can cause “distinct neural correlates” (Li & Jeong, 2019). In other words, the adult brain showed significant neuroplasticity concerning social interaction, contradicting the idea that only a young brain can respond to social learning successfully. Likewise, the use of body language to aid the understanding of speech in another language has a notable effect on SLA too.

The results showed that social interaction methods can result in stronger neural activities in important regions of the brain that are crucial for memory, perception, and action, which can increase both intake and long-term retention of the L2. Intake describes when input — any form of interaction to a L2 that someone finds in their environment — becomes more deeply understood to foster growth and development in linguistic competency (Montrul, 2013). The results suggest that there tends to be a significant impact of social interaction and quality time with native speakers of one’s L2 on their evolving SLA, which could very well be achieved through a dual-language board game.

V. Conclusion

Communication is the primary determinant of successful relationships between family members in any culture as it creates a common sense of belonging, connectedness, and love in the home. Thus, these identified problems caused by gaps in acculturation and SLE among Hispanic and Latin American immigrant family members require much more attention and resources to resolve.

With immigrants and their children representing 28% of the United States population, and 60.6 million Latin immigrants present in the country as of 2020, issues caused by disconnection between family members will only become more prevalent, as these intergenerational differences will have lasting effects on immigrant children’s mental health (Cox et al., 2021). In the midst of the current mental health crisis facing the entire country, the development of strategies that can mend bonds within families is incredibly important. Furthermore, as data predicts “88 percent of the US population growth over the next 50 years will be due to immigrants and their offspring,” a solution for this problem seems even more vital (Cox et al., 2021).

Improved interpersonal communication among family members experiencing these acculturation gaps are likely to lead to increases in each person’s abilities to understand their respective L2s. If an activity — like a dual-language board game — can make people feel motivated to practice the language less familiar to them with a native speaker, they should find more success in their L2 retention (Hernández, 2010). These effects would help older generations of immigrant families develop a greater acceptance of their host culture, while younger generations would become more familiar with their heritage culture. Studies show that adolescents who are proficient in their HL “report higher levels of ethnic identity,” allowing them to achieve “greater levels of resilience and life meaning” (Wang et al., 2022). Therefore, more programming, resources, and general attention to mitigating conflicts regarding acculturation gaps and SLE among Hispanic and Latin American immigrant families on a nationwide scale will create hope for happier children, more connected families, and a greater diversity of languages and cultures within the United States for years to come.

VI. Implementation

Main Goal

In an effort to connect Hispanic and Latin American immigrant family members experiencing acculturation gaps and SLE, the main goal of this creative project was to produce a functional board game for intergenerational bonding that features a mobile companion application component and the ability to be played in both English and Spanish simultaneously. This outcome will hopefully become applicable for additional uses in the future, such as integration into Spanish and English classrooms or the ability to translate the project into different dialects or languages for immigrant families throughout and outside of the Spanish-speaking world.

The inspiration for this project stemmed from the central idea of family. Family is an important aspect of life for Hispanic and Latin individuals; the act of coming around the table to share a meal or simple conversation is a common, yet sacred, practice. Even among busy schedules and differing priorities, a primary way families can come together and share quality time is around food or an activity — like a board game.

Personally, my fondest memories from my childhood are spending time with my family members while playing board games or card games. Since I was very young, I have always had an infatuation with the strategy, luck, and fun that games harness. I still enjoy playing games like Phase 10, Sorry!, Skip-Bo, Uno, Rack-o, or Monopoly with my parents and grandparents today. Even with the cards’ faded colors and boxes held together by yellowing Scotch tape, they evoke a sense of nostalgia while still remaining enjoyable for everyone. It is the best time for us to talk and enjoy each others’ company with minimal distractions.

As Spanish board games are not easily accessible in the United States and the few options available on the market are ridiculously overpriced, it is deeply upsetting that many Hispanic and Latin American families do not get to share these feelings and memories (“Hasbro Spanish Monopoly (EA),” 2022). Therefore, the goal in creating this project is to use every aspect of design learning and experience taught within the Communication Design curriculum at Elon University’s School of Communications and pair those skills with the illustrative and artistic influence of Hispanic and Latin American cultures around the world.

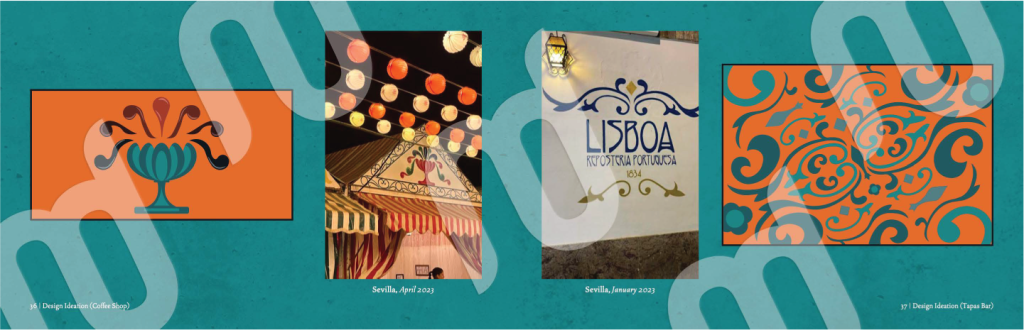

Methods & Timeline

This project began in the fall of 2022 with extensive research regarding the conflict that arises in Hispanic and Latin American families due to acculturation gaps and Shared Language Erosion, as well as the effectiveness of board games for familial connection and linguistic education. This research helped to justify the means for the project for the thesis proposal. Then, I moved to Seville, Spain for four months to study abroad and improve my Spanish proficiency. Throughout my wonderfully immersive spring semester in 2023, I formally studied communications, design, art, and wine through the Council on International Educational Exchange as well as La Universidad de Sevilla. Meanwhile, I continued to collect pieces of inspiration throughout the semester that would later fuel the ideation for this project — such as logos, graffiti, architecture, patterns, advertisements, typography, tiles, and textures. This practice was important to maintain during my time abroad because I had set a goal to only create designs for this project that were directly influenced by assets I found naturally in the Spanish-speaking world. With this intention, I hoped to create work that most closely represents and honors the culture(s) that I aim to emulate in order to cater towards the audience of this project as accurately as possible.

Upon my return to the United States, the next phase of this project included an intensive ideation process with my mentor to brainstorm the game concept. I examined and analyzed the photos I captured in Spain, Latin American and Hispanic graphic design books, some of my favorite board/card/video games, examples of board game engineering and other multilingual games online, and memories from other personal study abroad experiences in Belize, Peru, and Spain. All of these media helped to develop the design ideation process. After creating sketches and developing user personas to better understand the game’s target audience, I settled on the game: Antes del Sol.

The overall theme of the game felt more catered toward my study abroad experience and Spanish culture. Aside from simply being fun to play, my goal for the game was to be inclusive of all immigrant families of the Spanish-speaking world, and the second game concept had more promising applications for a wider audience. I also felt inspired by the incorporation of the “spirits” in the second game as religion feels so ingrained throughout the Spanish-speaking world, and I liked how luck would be intertwined with strategy to add more excitement and variety to each round.

Throughout the 2024 Winter Term, I finalized my research and continued sketching and creating collateral for the creative project. I spent time carefully determining the audience, brand archetypes, mission statement, etc. for the game’s “brand.” Then, I worked on even more sketches to determine the parameters for my physical designs, such as the final dimensions for board, box, pawns, cards, etc. I decided to abandon the idea of a two-sided game to integrate both languages more closely, in addition to resolving future manufacturing difficulties that might require. I quickly moved to the computer to begin creating these assets and prototypes with Illustrator, Photoshop, and Figma, before later working in downtown Elon’s Maker Hub to work on physical, high-fidelity prototypes for the board game. Once complete, I began exploring and experimenting with the game colors, typography, patterns, and textures, hoping to later match the mobile companion app to this base design.

Throughout the beginning of the Spring 2024 semester, I set out to develop the prototypes I created in the Maker Hub on the computer. Using Adobe Illustrator and Procreate, I designed a punchy, handwritten logo and the game board using an elaborate color palette. Every building, pattern, icon, and asset on the game board was inspired by or directly pulled from photos I took during my semester abroad in Sevilla, Spain. There are also three textures overlaid on the board, two of which were pulled from photos I took of the ground in Barcelona, Spain for the “street,” in addition to one high-quality image to add a layer of distressing on everything that was licensed from Adobe Stock images.

After the game was complete, I printed it in the Elon School of Communication’s (SOC) media graphics lab and pasted it on a piece of matboard in the Maker Hub for playtesting before sending it off for production. Once I wrote an official set of game instructions in both English and Spanish, I sent out a Google Form to create playtesting groups and receive consent from participants for the project. I used pieces of paper to act in the place of the app, as it was still under development at this time, and I took notes on how participants successfully played the game without my interference in the SOC’s Observation Room and Schar Hall Conference Room. Elon University IRB approval was waived for this project.

Playtesting & Feedback

In total, I had 17 Elon students sign up to playtest the game from flyers around campus, requests for playtesters online, or direct messages from me. These participants were used to create five playtesting sessions: two sessions with two players, one session with three players, one session with four players, and one session with six players. Four people self-identified as Latino/a/e/x or Hispanic, two as Asian, one as Black or African American, one as Multiracial, and 14 as White. Some playtesters selected multiple racial or ethnic identities. The majority of players that did not identify as Latino/a/e/x or Hispanic either had an interest in the Spanish-speaking world, graphic design, or board games, so this mix of individuals provided many exciting insights into how I could improve the success of the project.

I took notes as each session progressed to identify which struggles players encountered, which were mostly caused by a misunderstanding of the instructions or graphic design flaws. After someone was crowned “Sole Survivor” at the end of each session, I engaged in short feedback chats with each group to take note of their overall user experience, their ease of understanding the instructions and mechanics of the game, and their general level of visual appeal. For example, some questions I asked were:

- Did you enjoy playing the game, and would you play it again?

- Were the instructions easy to follow? Did any phrasing or rules confuse you?

- How did visual design aesthetics affect your experience? What did you like or dislike?

- Do you have any suggestions for how I could make the game better or more fun/exciting?

The most common issues I noticed or was told by the participants were related to confusing game terminology and struggles to remember penalties for certain actions, but I received at least one suggestion from every playtest session that was later incorporated into the design or instructions. Shockingly, in the first two sessions, every player evaded the Spirit attacks and made it to the very end of the game. They were then challenged to acquire more Save or Wild cards than the other player to survive more of the (inevitable) attacks than the other player to win. After session 01, I simplified the instructions on how to start the game and decided to write the penalties to use the cards on the back of each. After session 02, I decided to create Spirit Space tokens for players to keep track of which buildings are unsafe on the board itself.

On the other hand, two players in session 08 went out on the very first round and ended up feeling “a little bored” as the other players finished their game. This inspired me to create a way to re-enter the game through a chance at Revival. I also worked with this group to heavily simplify the language of the game; the instructions now only discuss “moves,” “rolls,” “Days,” and “games.” Words like “turn” and “round” being used interchangeably caused players to experience unnecessary confusion. I also brainstormed with this group about how to add more contrast to the colors on the board for better legibility of the building names and easier identification of the doors. This was also the final game I held before introducing “Dusk” to further simplify how advantages are used at the end of each Day.

After session 09, I was encouraged to simplify the varying levels of penalties players receive for different actions and the occasional compounding rules for cards and Spirit Spaces, as those all became tedious or difficult to remember. This group also wanted to incorporate a more competitive aspect to the game, so I decided to add a chance for players to unlock the ability to steal a card from an ATM. Lastly, session 10 was helpful in allowing me to find final tweaks and clarifications for the instructions. I decided to double the size of the Thrift Store, as it seemed to be frequently overshadowed by other buildings despite having one of the most exciting advantages in the game. It was very exciting to see how well the game worked with a larger group in this session. I was also thrilled that half of the group in session 10 chose to only speak in Spanish, which allowed me to witness the dual-language feature of the game in action.

One participant from this session in particular, who is the first in her Mexican- American family to be born in the U.S., shared that she would love to play the game with her grandparents. She explained, “when my grandparents come to visit, we try to translate and explain games as best as possible, but they eventually get bored and opt out because they don’t get to experience the fun of the game as often. They don’t get to do any of the strategical thinking, just playing in whatever way they are told. I would love to bring this game home to show my family and keep the fun in family game night.” This quote shows how Antes del sol’s simple objective and English-Spanish integration would allow them to all play a game together that everyone can finally enjoy equally, while eliminating this need for language brokering during a family activity. Furthermore, another Hispanic participant shared, “We’ve never been able to have my Spanish-speaking grandparents over because the language barrier makes it difficult to explain and play games together, especially when my dad speaks no Spanish and my Abuela speaks very little English. I would love to have this game in my home as a way to connect with my Spanish-speaking family through board games in the same way that I’ve been able to with my English- speaking family through the years.” Both of these quotes reminded me how the game could have such an immense impact on immigrant families across the country; the want for it is so much more tangible through the words of these playtesters.

Overall, the playtesting process was crucial in developing this game into a more successful project. It was a challenge to decipher the line between which confusions or UX issues I could solve through my designs or instructions and which issues I could not resolve due to players simply not reading the instructions closely or needing to play for a few minutes before finally understanding how everything worked. All participants reported that they would like to play the game again, and most shared many positive comments about how the vibrancy and layout of the design impacted their experiences.

It was entertaining to watch how players took ownership of the game too. I strategically left some rules up for interpretation, such as whether players could move diagonally across the tiles, because I found that people became much more invested in the game when they could develop their own “house rules.” I was also very pleasantly surprised to find that about half of the playtesters actually chose to play the game cooperatively — like a sort of allyship against the Spirits. This outcome was very exciting, as I witnessed players bonding through teamwork in addition to competition throughout these sessions. It was a strategy I never predicted. I believe that this benefit would help immigrant family members connect even more by playing this game.

Almost exactly as I had hoped when designing the game, players spent an average of about 8.5 minutes reading and discussing the instructions, plus an average of about 30 minutes playing. Play times did not seem to increase too dramatically as more players entered the game due to its luck-based nature. However, the final session of 6 playtesters lasted the longest amount of time, ending after about 50 minutes. All participants received a $15 gift card for their assistance in developing Antes del sol.

During this time, I also set up a meeting with Brigette Indelicato, a graphic designer and creative director who has nine years of experience in the game design industry. She gave me feedback on the design on the board in addition to my playtesters, especially with tips on accessibility and strategies to further enhance my intricate designs. Brigette also directed me to The Game Crafter, a manufacturer that could produce my game efficiently and affordably before my defense date. While I found limitations with the standard sizes of game boards available across many sites, I was able to scale down the prototype into a smaller version through this company that would still be playable and legible for the defense. They were also able to produce my entire box as well as all of the cards, tokens, pawns, and dice.

Final Product

The final game is a bi-fold, 9” by 18” board with a variety of cards, tokens, pawns, a die, and instructions inside the fully designed box. There is also a functional prototype for the companion app created with Figma. All creative components of the project, in addition to my design process, are compiled in the Antes del sol Brand Book. This book includes: the game logo and brand identity; brand standards and archetypes; user personas; details regarding the ideal consumer base; a breakdown of the visual elements of every building and asset in the game, paired with their inspiration from my semester abroad in Spain; advertising materials to market the game; and sketches, pictures, and notes throughout the design process. Examples of the product can be seen in the Appendix section.

Future Development

Due to general limitations regarding my available resources for the execution of the project, as well as my availability as a full-time college student to develop this project individually, there are a few things I would like to change or expand upon should this game have a life beyond Elon. Ideally, I would hope to sell it to a company like Hasbro to get it off the ground, or better yet, be hired by a company that wants to help me bring it fully to fruition. The first thing I would change is the size of the final game; the original 12” by 24” prototype worked very well for playtesting, and I would like to return to that original size with a custom game board and box. Unfortunately, custom games require much more intensive processes to produce and are more expensive to create as a result, making that inaccessible for the thesis defense. I also enjoy the use of the companion app in conjunction with the board game, but I could not fully develop it beyond an animated prototype. I envisioned additional features for its functionality — many involving auditory components — that I was not able to include in the first version.

After successfully using little pieces of paper to function in the place of the app throughout the playtesting sessions, I also thought about creating a version of the game that solely uses cards. While I believe this would make some rules slightly more difficult to understand and would require players to mediate the game themselves, I also want to consider how the app component may be inaccessible to some players who do not have a smartphone or tablet in their home. Therefore, I think that this version could still act as a decent option for those who cannot use the app or would rather play an “unplugged” game.

Clearly, there are clearly many different ways to help this game explore new horizons. I considered how the Antes del sol concept could easily be applied to other languages and cultures around the world for future expansion. As the game mechanics themselves do not have much to do with the Spanish-speaking world, different designs could be applied to the board for immigrant families facing acculturation gaps and SLE all over the world. Furthermore, I considered how the original version of the game could be developed further to include additional advantages or Special Stores for veteran players. Especially through software updates or in-app upgrades, these expansion opportunities would be more accessible than the current industry standard by not requiring players to buy a new game or an additional deck of cards.

VII. Personal Reflection

It is difficult to believe that this project is finally complete after two years of researching, planning, creating, testing, revising, producing, and playing my own board game. Antes del sol has definitely been a simultaneous “passion project” and “thorn in my side” throughout the most stressful yet most life-changing chapter of my life, and it would be an understatement to say that this finish line is solely an accomplishment. This game feels like a poetic culmination of my Elon experience: it ties together both of my majors in Communication Design and Spanish into one piece, while showing off my design skill set for my future career with an extensive project that was informed by my academic background as an Honors Fellow. Best of all, I think I created something fun that can spread joy in the world, especially by developing a special product for people who never knew they needed it. Just having the potential to positively impact people in immigrant communities who face invisible struggles that no one knows how to resolve feels like an incredibly fulfilling legacy, especially if this game takes on a life of its own after graduation.

I came to Elon and began the Honors program unsure of what research would look like for me. I was, honestly, very averse to the idea. However, I am very proud of myself for pushing my limits and developing an impressive project that will represent my alma mater (and me) for years to come. Also, this kind of dual-language board game does not even exist — at least according to what I have scoured the internet to find. Therefore, I am extremely excited that I was able to use my design background and my Elon resources to invent something novel and purposeful.

I hope my project will serve as a helpful precedent for future Communication Design students who hope to go down a more creative path with their research. While it may feel like more work than a traditional thesis, I have found the ability to identify a problem and solve it with a piece of art is so much more powerful and personal than writing a really long paper. I believe that solving problems through art and visuals is the root of everything I intend to do as a designer and art director. Therefore, despite any difficulties and challenges I faced along the way, I am thankful that I was able to start my professional journey with this extensive body of work that not only displays what I can achieve, but that also represents who I am as a creative person and global citizen.

Acknowledgements

To Professor Rebecca Bagley, my incredible mentor and unpaid therapist, thank you so much for your unwavering kindness and support throughout this two-year endeavor. I am so excited to see where we can take this project beyond Elon. To Jessi Jennings, my favorite collaborator and design pal, thank you for always helping me achieve my greatest potential and bringing joy to the days that need it most. Special thanks to Dr. Harlen Makemson, Dr. Ketevan Kupatadze, my wonderful playtesters, my best friends, and my family back home — I feel so lucky to have a support system that keeps me going every day.

References

Alba, R. et al. (2002). Only English by the third generation? Loss and preservation of the mother tongue among the grandchildren of contemporary immigrants. Demography, 39(3), 467-484. https://doi.org/10.2307/3088327.

Birman, D., & Poff, M. (2011). Intergenerational differences in acculturation. Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development. https://www.child-encyclopedia.com/immigration/according-experts/intergenerational-differences-acculturation.

Brunscheen-Cartagena, E. et al. (2019). Bonding thru board games, fact sheet. K-State Research and Extension. https://bookstore.ksre.ksu.edu/pubs/MF3401.pdf.

Chang, Y. et al. (2022) Effects of board game play on nursing students’ medication knowledge: A randomized controlled trial. Nurse Education in Practice, 63, 103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2022.103412.

Collins, K. et al. (2011). It’s all in the game: Designing and playing board games to foster communication and social skills. YC Young Children, 66(2), 12–19. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42730714.

Cox, R. et al. (2021). Shared language erosion: Rethinking immigrant family communication and impacts on youth development. Children, 8(4), 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8040256.

Dörnyei, Z., & Clément, R. (2001). Motivational characteristics of learning different target languages: Results of a nationwide survey. Motivation and Second Language Acquisition, 23, 399-432. https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/ba734f_a57598b17ebd411dbcdc83c32b8e0d16.pdf?index=true.

Fjællingsdal, K., & Klöckner, C. (2020). Green across the board: Board games as tools for dialogue and simplified environmental communication. Simulation & Gaming, 51(5), 632–652. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878120925133.

Hasbro Spanish Monopoly (EA). (2022). Retrieved from https://www.amazon.com/Hasbro-Gaming-08009-Monopoly-Spanish/dp/B00000IWET.

Hernández, T. (2006). Integrative motivation as a predictor of success in the intermediate foreign language classroom. Foreign Language Annals, 39(4), 605-617. https://epublications.marquette.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1064&context=span_fac.

Hernández, T. (2010). The relationship among motivation, interaction, and the development of second language oral proficiency in a study‐abroad context. The Modern Language Journal, 94(4), 600-617. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2010.01053.x.

Isabelli-García, C. (2006). Study abroad social networks, motivations and attitudes: Implications for second language acquisition. Language learners in study abroad contexts, 231–258. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=hispstu_scholarship.

Isabelli, C., Nishida, C., & Eddington, D. (2005). Development of Spanish subjunctive in a nine-month study-abroad setting. Selected Proceedings of the 6th Conference on the Acquisition of Spanish and Portuguese as First and Second Languages, 78-91. https://www.lingref.com/cpp/casp/6/paper1127.pdf.

Kinginger, C., & Farrell-Whitworth, K. (2005). Gender and emotional investment in language learning during study abroad. CALPER Working Papers Series, 2, 1-18. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25173139.

Latine vs. Latinx. Which should we use? (2021). LATV Network. Retrieved from www.youtube.com/watch?v=oHKA5AtpieY.

Li, P., & Jeong, H. (2019). The social brain of language: Grounding second language learning in social interaction. NPJ Science of Learning, 5(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-020-0068-7.

Matanzas Rodríguez, M. (2016). La Motivación En La Adquisición de Una Segunda Lengua. UCrea. http://hdl.handle.net/10902/8829.

McGee, V. (2022). Latino, Latinx, Hispanic, or Latine? Which term should you use? Best Colleges. www.bestcolleges.com/blog/hispanic-latino-latinx-latine/#:~:text=Latine%20came%20to%20mainstream%20use,use%20of%20%22e%22%20instead.

Montrul, S. (2013). El bilingüismo en el mundo hispanohablante. John Wiley & Sons.

Nesteruk, O. (2022). Family dynamics at the intersection of languages, cultures, and aspirations: Reflections of young adults from immigrant families. Journal of Family Issues, 43(4), 1015–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X211007527.

96% of families playing games feel closer. (2013). Retrieved from https://www.theboardgamefamily.com/2013/11/families-playing-games-feel-closer/.

Noe-Bustamante, L. et al. (2020). About one-in-four U.S. Hispanics have heard of Latinx, but just 3% use it. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2020/08/11/about-one-in-four-u-s-hispanics-have-heard-of-latinx-but-just-3-use-it/.

Portes, A., & Schauffler, R. (1994). Language and the second generation: Bilingualism yesterday and today. The International Migration Review, 28(4), 640–61. https://doi.org/10.2307/2547152.

Schrade, A. (1994). Gamesplay in Spanish teaching. Hispania, 77(3), 519–23. https://doi.org/10.2307/344987.

Verhaeghe, F. et al. (2022). Meanings attached to intergenerational language shift processes in the context of migrant families. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(1), 308–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1685377.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press. https://www.hup.harvard.edu/books/9780674576292.

Wang, J. et al. (2022). Family environment, heritage language profiles, and socioemotional well-being of Mexican-origin adolescents with first generation immigrant parents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 51(6), 1196–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-022-01594-5.

Wood, D., Bruner, J., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychiatry and Psychology, 17, 89-100. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00381.x.

Yildiz, Y. (2016). The role of extracurricular activities in the academic achievement of English as foreign language (EFL) students in Iraqi universities (A case of Ishik University Preparatory School). International Black Sea University, 3-24. https://ibsu.edu.ge/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Yunus-Yildiz-Extended-Abstract-ENG-FINAL-PRINT-2.06.2016.pdf.

Yilmaz, T. (2016). The motivational factors of heritage language learning in immigrant bilingualism. International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, 6(3), 1-9. http://www.ijssh.net/vol6/642-H033.pdf.

Zakhir, M. (2019). Extracurricular activities in TEFL classes: A self-centered approach. Sisyphus Journal of Education. https://doi.org/10.25749/sis.17590.

Appendix

Board game box

Inspiration page from brand book

Mobile app interface

Mock advertisement