- Home

- About

- Committee on Elon History and Memory

- Freedom Footprints: A Juneteenth Journey through Elon’s Black History

Freedom Footprints: A Juneteenth Journey through Elon’s Black History

Freedom Footprints: A Juneteenth Journey through Elon’s Black History

Welcome home alumni, family and friends! We have adapted this Juneteenth tour to be offered during Homecoming weekend so you can learn some of Elon’s Black history. Welcome to your Juneteenth at Elon self-guided walking tour. Primary walking tour stops are denoted by number; other historically significant campus sites are denoted by an arrow. We hope you enjoy this walking tour.

This Google map contains the stop points outlined below. The primary Juneteenth Walking Tour is marked with red. Other sites of interest are marked with yellow. The suggested route to follow is marked with blue letters.

Stop 1: Moseley Center

Portraits of Glenda Phillips Hightower and Eugene Perry

Inside the Young Commons entrance to Moseley Center are the portraits of Glenda Phillips Hightower and Eugene Perry. Phillips enrolled at Elon in the Fall of 1963 as Elon’s first full-time Black student. She attended the college for one year. Perry enrolled in the fall of 1965 and in 1969 became the first Black student to graduate from Elon College. The annual Phillips-Perry Black Excellence Awards Banquet, which celebrates the academic and leadership accomplishments of Black students at Elon, is named in their honor.

Inside the Young Commons entrance to Moseley Center are the portraits of Glenda Phillips Hightower and Eugene Perry. Phillips enrolled at Elon in the Fall of 1963 as Elon’s first full-time Black student. She attended the college for one year. Perry enrolled in the fall of 1965 and in 1969 became the first Black student to graduate from Elon College. The annual Phillips-Perry Black Excellence Awards Banquet, which celebrates the academic and leadership accomplishments of Black students at Elon, is named in their honor.

Learn more about Glenda Phillips Hightower and Eugene Perry

Center for Race, Ethnicity, and Diversity Education / Black Community Room / Wall of Fame

The second floor of Moseley is home to the Center for Race, Ethnicity, and Diversity Education, better known as the CREDE. The CREDE was named in 2014 to reflect its focused mission and goals as the university’s dedicated resource for race- and ethnicity-related advocacy, services and programs.

The space was originally known as the African American Resource Room, which opened in Moseley in 1994 to create and maintain supportive programs for the development and advancement of African American students. It was led by L’Tanya Richmond ’87, who created the “Wall of Fame” to educate the campus community about the major achievements of African American students and organizations that foster African American culture at Elon. The mission of the African American Resource Room was expanded to serve the increasingly diverse student population and to support diversity education opportunities for all students. To this end, the Multicultural Center was established in the Resource Room location.

The Wall of Fame is now located in the Black Community Room, just down the hall from the CREDE in Moseley 213-1.

Learn more about Elon’s first Black students

Janice Ratliff Building

Just behind the Moseley Center stands the Janice Ratliff Building. Home to the Office of Residence Life, the Office of Student Care and Outreach, and Office of student conduct, the Janice Ratliff Building is the first campus building to be named for a Black Elon staff member. The name is a tribute to the contributions of Ratliff, who spent 35 years serving the university and its students and is particularly known for her student mentorship.

Just behind the Moseley Center stands the Janice Ratliff Building. Home to the Office of Residence Life, the Office of Student Care and Outreach, and Office of student conduct, the Janice Ratliff Building is the first campus building to be named for a Black Elon staff member. The name is a tribute to the contributions of Ratliff, who spent 35 years serving the university and its students and is particularly known for her student mentorship.

Read more about the building dedication

Stop 2: Alumni Gym

Black Student-Athletes

In the years after integration, athletics provided an important route for Black students to attend Elon. In the 1970s and 1980s, for instance, between one-quarter and one-third of Black students at Elon played a sport. The available information on the first generation of Black student-athletes at Elon suggests that they faced many of the same struggles Black athletes faced at predominantly white institutions around the country, and that they responded to those struggles by turning to activism, both individually and in solidarity with other Black students.

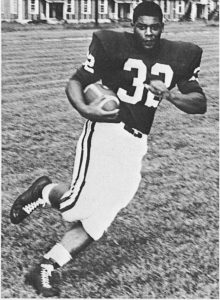

Emery Moore was among the first Black student-athletes at Elon.

Emory Moore, a standout running back for the Elon football team, was one of the first Black student-athletes to attend Elon when he arrived in 1966. He and his brother Ralph, who followed Emory to Elon, exemplified the pattern of performance on the field and advocacy off of it. Ralph even had his own column in the alternative student newspaper, Veritas Liberated Press (1968-1970), devoted to educating his fellow students about Black Americans’ claims to full equality. Titled “Dear Beverly Axelrod,” the column was easily one of the most direct assaults on White supremacy that any student paper published during the period.

Flash forward to the new millennium: In fall 2022, 18% of all student-athletes at Elon were Black, far outpacing the overall figure of 6% of undergraduates. That same year, faculty researchers at Elon were awarded a grant from the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics to undertake a project titled “Building a Meaningful Program with and for Black College Athletes at a Predominately White Institution.” The project aimed to explore the mentoring needs of Black athletes at Elon as well as their overall experience, with the long-term goal of providing support to and deepening the connections of Black student-athletes on campus.

Learn more about Elon’s Black student-athletes

Stop 3: West Hall

Elon founding and Black labor at Mill Point

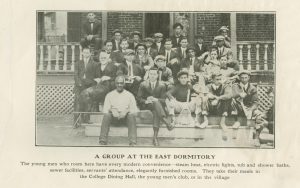

A photo from the August 1913 Bulletin of Elon College of East Dormitory residents featuring Pinkney Comer, retired clergyman James W. Wellons, and other unidentified individuals.

When Elon College was established in 1889 its founders imagined it as a place for white people, but Black people have contributed their labor to the success of Elon College from the institution’s earliest days. For example, in the first part of the 20th century, Sam Haith operated a farm on behalf of the college.

Unfortunately, records do not exist to document the names and roles of many of these early staff members, though oral histories could fill in many of the gaps — especially from families with long, multi-generational connections to the institution like the Haith, Covington or Miles families.

One name stands out in the sources: Pinkney Comer (front row, far left, in photo above). Comer came to Elon between 1906 and 1910 to assist in the care of retired clergyman and Elon College founder James W. Wellon. Wellon lived in a room in West Dormitory, which at that time had been usually reserved for women, from 1910 to 1923. In addition to caring for Wellon, at some point Comer also began maintaining the athletics facilities for the college.

Learn more about Pinkney Comer and Black labor at Elon

Comer Field / Station at Mill Point

In 1919, the construction of new athletic fields was completed in the location that is now The Station at Mill Point. In 1920, a year after the fields were completed, one of Elon’s Black laborers, Pinkney Comer, died while crossing the train tracks. School officials posthumously named the new playing facility “Comer Field.” This was the first space on Elon’s campus named for a Black employee. Comer Field was destroyed in 2012 when The Station at Mill Point was built, but the name is also informally used for the intramural fields on the south side of campus. In 2020, the Janice Ratliff Building became the second space on campus to have been named in honor of a Black employee, exactly 100 years after Comer Field.

Read an Elon University Archives blog post about Comer Field

Stop 4: Alamance Building

Black Studies protests / African & African American Studies

On Nov. 19, 1969, students of the Third Front of the Organization of Afro-American Unity at Elon College sent an open letter to the chair of the Department of Social Science, Durwood T. Stokes. The letter requested a course in Black studies at Elon College be taught during the fall term of the 1970-71 academic year and suggested that Charles Harper teach the course. It also requested the hiring of at least one Black professor with expertise in Black history by the fall of the 1971-72 academic year and the immediate resignation of Professor Luther Byrd over charges of overt bigotry. The students’ requests fell on deaf ears, and, in fact, years later, Stokes would omit key details of the incident in his book on Elon’s history, “Elon College: It’s History and Traditions.”

Throughout the early 1970s, students continued to voice their frustration with the lack of Black studies in the Elon curriculum, particularly through the alternative student newspaper, the Veritas Liberated Press (1968-70), and the short-lived precursor to the Pendulum, Dimensions Today (1974). In 1974, the Black Cultural Society at Elon College was formed “1. To promote understanding and a sense of unity among Black students. 2. To encourage Elon College to achieve a greater awareness and appreciation of the culture and achievements of Black people. 3. To attack with vigor all injustices and inequalities that may exist on the campus of Elon College with respect to Black People. 4. To support and assist in any way possible the communities immediately surrounding Elon College.” In 1978, the BCS urged the Student Government Association to advocate for a Black studies course. This time, the request was successful, and a Black literature course was introduced in 1979.

Throughout the early 1970s, students continued to voice their frustration with the lack of Black studies in the Elon curriculum, particularly through the alternative student newspaper, the Veritas Liberated Press (1968-70), and the short-lived precursor to the Pendulum, Dimensions Today (1974). In 1974, the Black Cultural Society at Elon College was formed “1. To promote understanding and a sense of unity among Black students. 2. To encourage Elon College to achieve a greater awareness and appreciation of the culture and achievements of Black people. 3. To attack with vigor all injustices and inequalities that may exist on the campus of Elon College with respect to Black People. 4. To support and assist in any way possible the communities immediately surrounding Elon College.” In 1978, the BCS urged the Student Government Association to advocate for a Black studies course. This time, the request was successful, and a Black literature course was introduced in 1979.

Although Elon hired a full-time Black faculty member, Julia W. Covington, in 1970, she left after only one year. Elon didn’t hire another Black professor until 1987, when Wilhelmina Boyd joined the faculty. Boyd founded the interdisciplinary minor program African and African-American Studies at Elon (AAASE) in 1994. It celebrated its 30th anniversary in 2024 with a series of events aimed to showcase “the deep significance, breadth and enduring influence of this exceptional minor.”

Visit a digital exhibit on the fight for Black studies at Elon

Flashpoint for Integration

Photograph of Mary Carroll when crowned Homecoming Queen in 1979.

Elon’s Historic Neighborhood is home to another episode in Elon’s history, one that starts with an act of anti-Black racism but ends with a powerful example of Black resistance.

Mary Carroll Robertson (nee Mary Carroll) arrived at Elon in the fall of 1977 and was elected as Homecoming Queen in 1979. Carroll’s election was a high honor. However, some white students booed Carroll when she was crowned. Adding to the injury, white students editing the yearbook did not include the customary Homecoming spread in the 1979-80 edition of the yearbook. In a 2004 interview, Robertson recounted how it felt when she first looked in the 1980 Elon College yearbook but could not find the annual homecoming spread, which should have featured her coronation as the first Black Homecoming Queen. “It was as if I didn’t even exist on campus,” she remembered.

Black students did not let the insult be the last word. A huge groundswell of Black students led by football players Alonzo Craig ’81 and James Strickland ’82 risked forfeiting scholarships and their academic standing to protest. Students marched down by the dozen to the administration building (today’s Alamance Building) and burned their yearbooks in one of the boldest student protests in Elon history.

Read more about Mary Carroll and the problem of erasure

Black Institution at Elon

In 2023, the Black Lumen Project, under the direction of Professor Buffie Longmire-Avital, released the inaugural edition of its biennial report, “The Black Experience at Elon.” In it, Longmire-Avital defines Black Institution as “a reflection of synergies among the many spaces, people, programs, and initiatives that aim to advance and weave the Black experience into all aspects of university life.”

In addition to its many illuminating statistics — for instance, that 9% of faculty and 16% of staff self-identify as Black, and that the undergraduate share of Black students hovers just below 6%, whereas representation is at 12% for Elon’s graduate programs — the report shines a light on the Black administrators who are driving the school forward.

One such leader is Janet Williams, who is vice president for finance and administration and oversees the largest unit of staff at the university. Her departments include Business and Finance, Human Resources, Facilities Management, Information Technology, Campus Safety and Police, Auxiliary Services, Administrative Services, Internal Audit, and Planning, Design and Construction. That means Williams is both literally and figuratively building Elon up from her office in Alamance Building. Williams joined the university in 2021 after a national search, bringing nine years of experience in higher education — most recently at Wake Forest University — and 29 years of experience in business and industry. She has a bachelor’s degree in accounting, an MBA, and is a member of the CPA societies in North Carolina. She is also active with several community organizations in North Carolina.

One such leader is Janet Williams, who is vice president for finance and administration and oversees the largest unit of staff at the university. Her departments include Business and Finance, Human Resources, Facilities Management, Information Technology, Campus Safety and Police, Auxiliary Services, Administrative Services, Internal Audit, and Planning, Design and Construction. That means Williams is both literally and figuratively building Elon up from her office in Alamance Building. Williams joined the university in 2021 after a national search, bringing nine years of experience in higher education — most recently at Wake Forest University — and 29 years of experience in business and industry. She has a bachelor’s degree in accounting, an MBA, and is a member of the CPA societies in North Carolina. She is also active with several community organizations in North Carolina.

Read the Black Lumen Project’s full report

Iris Holt McEwen Building / School of Communications

The Iris Holt McEwen Building, part of the Elon School of Communications, has been a site of both triumph and controversy in the long and continuing march toward racial justice at Elon University. Because so many of the university’s publications originate in the school, the choices made within the building have had an outsize effect on Elon’s documentary record, in which Black people have historically been marginalized or excluded. For instance, the 1979-80 school yearbook, which erased Mary Carroll Robertson’s historic selection as Elon’s first Black Homecoming Queen, was produced in the McEwen Building. These stories of discrimination often overshadow stories of success, like that of Bryant Colson ’80. In the late 1970s, Colson became the first Black editor-in-chief of the Elon student newspaper, The Pendulum, and the first Black president of the university’s Student Government Association.

Stop 5: Powell Building

Division of Inclusive Excellence

As part of its strategic plan for 2030, Boldly Elon, the university committed to “advancing a more diverse, equitable and inclusive community.” One of the first steps toward achieving that goal was the creation of the Division of Inclusive Excellence, whose aim, according to the 2023 Black Lumen Project report, is to “provide leadership and coordination of existing resources while identifying new ones to achieve [the strategic plan’s] vision.”

The leaders of the division, a group headed by Vice President for Inclusive Excellence Randy Williams, serve as a hub, formally connecting campus offices like Academic Affairs, Admissions, Athletics, Student Life and University Communications, among others, in the joint effort to build a “college for the world.”

The division’s programs include regular assessments of the university climate vis-a-vis diversity and inclusion, an office that responds to reports of bias and discrimination on campus, and a range of educational and development opportunities for faculty, staff, and students. In particular, the Black Lumen Project, led by Professor Buffie Longmire-Avital, seeks to respond to institutional anti-Blackness and to illuminate Black Institution, defined as “a reflection of synergies among the many spaces, people, programs, and initiatives that aim to advance and weave the Black experience into all aspects of university life.”

Learn more about Elon’s Division of Inclusive Excellence

Stop 6: Belk Library

Colonnade Plaques and Locating Slavery’s Legacies

The colonnades leading away from the entrance of Belk Library toward Haggard Avenue include plaques displaying an abbreviated history of Elon from its founding in 1889 through 2009. The plaques are often viewed as a celebration of the university, as they describe moments of innovation and triumph in the face of adversity. However, many observers have noted that the plaques represent only one version of the school’s history and do not mention the significance of Elon’s founding as a co-educational institution, integration or the presence of Black labor on campus. Furthermore, BIPOC (Black, indigenous and people of color) students are only mentioned as athletes and scholarship recipients. Class discussions about the plaques invite students to consider the audience the plaques are currently intended to reach and to imagine how and where other celebratory moments that highlight diversity, equity and inclusion can also be included.

In an effort to provide a richer history, staff at Elon University Archives and Special Collections have adapted episodes from the 2020 Committee on Elon History and Memory report for inclusion in the Locating Slavery’s Legacies Database, an initiative sponsored by Sewanee, the University of the South, that began its work in 2017 as part of its Roberson Project on Slavery, Race, and Reconciliation. Elon was invited to partner with Sewanee and other higher education institutions “to collect information about monuments and memorials identified with the Civil War and Confederacy on the campuses of American colleges, which is then analyzed to understand the impact of Lost Cause movements on higher education in the United States in the 160 years after emancipation.”

Browse the Locating Slavery’s Legacy Database

Portrait of Andrew Morgan

Andrew Morgam standing next to his car, circa 1950s.

The portrait of Andrew Morgan that hangs in the Oak Grove Lounge at the south end of the Belk Library building is the oldest likeness on campus honoring a Black person. The portrait was painted from a photograph in 1962 by W. W. Sellars, who won a prize for the portrait and then donated it to the college.

Andrew Morgan was born in 1900 in the Pleasant Grove community of northern Alamance County. He and his wife, Hattie Burton Morgan, lived in the Ball Park community of Elon near where The Station at Mill Point now stands. He was known by family and friends to be a generous foster parent and faithful trustee of Arches Grove Church. Morgan joined Elon in 1926 as a campus maintenance worker. He worked at Elon for 38 years until his untimely death in 1964 due to an electrical accident while working at his home.

Members of the Elon College community mourned his death, and then-President J. Earl Danieley delivered the eulogy at his funeral, titled “Andrew Morgan was a Big Man.” Alumni sent in significant sums of money for the Andrew Morgan Scholarship Fund. Despite this outpouring of love, the 2020 Committee on Elon History and Memory report describes instances of cruelty and racism inflicted on Morgan by students and staff throughout his decades of employment. The episode of the report in which Morgan’s life is described along with the life of Pinkney Comer, a Black man who worked at Elon before Morgan, sheds light on the complexity of appreciation for the labor but with limited appreciation for the persons.

Learn more about Andrew Morgan and Black labor at Elon

Colonnades Building E

When completed in 2011, the Colonnades Residence Halls, located just beyond the Koury Business Center, were named for members of the Elon community: Story, Moffitt, Kivette, Staley and Harper. Elon’s fourth president, William A. Harper (1911–31), embodied the paradoxes of white Southern progressivism in the early years of the 20th century. White Southern progressives believed in the power of education and expertise to bring about moral, political and economic progress for all, though they insisted that White supremacy was an essential characteristic of a well-ordered society — something Harper wrote about in a 1910 article written on the occasion of Jack Johnson’s famous boxing victory, which had made Johnson the first Black heavyweight champion of the world. In 2020, upon learning of Harper’s 1910 Christian Sun article promoting an Elon education as a means of maintaining racial supremacy over Black people, President Connie Ledoux Book shared the information, and the article, with the board of trustees. They collectively agreed to immediately remove Harper’s name from the residence hall. In 2024, the building was named in honor of Noel Allen ’69, who has served in the Elon University Board of Trustees for nearly four decades and played an integral role in helping shape Elon across multiple generations.