This timeline is provided to help show how the dominant form of communication changes as rapidly as innovators develop new technologies.

A brief historical overview: The printing press was the big innovation in communications until the telegraph was developed. Printing remained the key format for mass messages for years afterward, but the telegraph allowed instant communication over vast distances for the first time in human history. Telegraph usage faded as radio became easy to use and popularized; as radio was being developed, the telephone quickly became the fastest way to communicate person-to-person; after television was perfected and content for it was well developed, it became the dominant form of mass-communication technology; the internet came next, and newspapers, radio, telephones, and television are being rolled into this far-reaching information medium.

Development of Radio

World Changes Due to Radio

Radio Predictions

The Development of Publicly Available and Adopted Radio

Experiments by Heinrich Rudolf Hertz between 1880 and 1890 proved the existence of electromagnetic waves. His successful work took place after earlier scientists explored and theorized about a potential connection between electricity and magnetism. Hertz’s work showed electromagnetic radio waves could be transmitted through free space and detected over a short distance.

This discovery motivated scientists and innovators in many corners of the world to find new applications for this new knowledge.

While many inventors worked to develop and perfect the elements necessary to make and distribute the earliest radio devices and networks between 1890 and the 1930s, the individual most famous at the time for playing a key role in the development of radio in the form commonly used by the public was Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi (pictured at right). Marconi earned the largest amount of positive publicity about it globally and thus succeeded in winning the financial backing to become the person best known at the time as the leading light in the rapid adoption of radio.

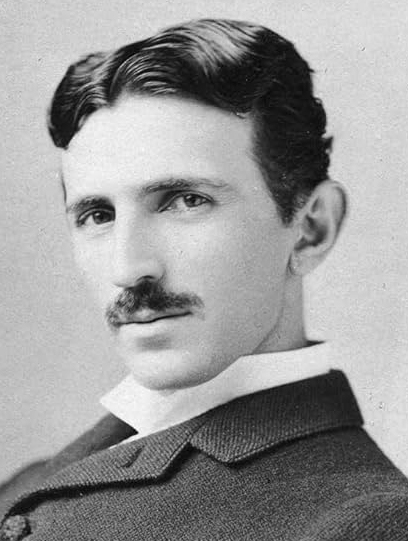

It is important to note that many other inventors were doing research and testing radio applications at the time. Most prominent among them was Nikola Tesla. And at least four companies were developing their own approaches to radio by 1900. Historians say Marconi’s success in winning the public relations battles at the turn of the century was due to the fact that his family was well connected with the British aristocracy.

In 1895, in his first successful demonstration, Marconi sent a wireless Morse Code message to a source more than a kilometer away. In 1896, he took out a patent for the first “wireless telegraphy” system in England. Several inventors in Russia and the United States were working on similar devices, but over the next decade Marconi made the right political and business connections to gain global acclaim for his development of radio. Thomas Edison and Andrew Carnegie invested in his company. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1911 for his contributions to the great leap in global communications.

Marconi had applied luck and ingenuity to jump to the head of the line against many other accomplished inventors. Foremost among them was Tesla (pictured at right). In the early 1890s Tesla began researching uses of electromagnetic waves. He filed a basic patent application for key elements in the development of radio in the U.S. in 1897 and it was granted a few years later. However, at that time he was primarily interested in using them to create a system he proposed that would use the Earth itself as the means to conduct long-distance signals. This approach was different from the form of radio transmission developed by Marconi and others, but significantly related to it in many aspects.

Between 1901 and 1906 Tesla developed an experimental wireless-transmission station at Shoreham, NY, called Wardenclyffe Tower. The facility was built to transmit messages, telephony and facsimile images across the Atlantic Ocean to England and to ships at sea – all based on his theories of using the Earth as a conductor. But it didn’t quite get off the ground. Tesla lost the monetary support of his project’s financier, banker J.P. Morgan, when he asked for more funding to expand the plant in order to compete with Marconi’s new system. Tesla could find no new investors and the plant was abandoned in 1906.

Despite the fact that Tesla had been granted a U.S. patent for radio-related equipment in 1900, in 1904 the U.S. Patent Office granted Marconi a patent for the invention of radio. Some historians believe this happened due to Marconi’s fame and connections; some say it was deserved. Marconi became known as the “inventor” of radio. However, that 1904 patent award decision for Marconi was reversed by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1943. The decision in Marconi Wireless Corporation of American v. United States returned most of the original patent rights to Tesla. The decision in this complicated court case was not unanimous and some people still argue about it today.

In the years just prior to World War I, scientists at companies such as American Telephone and Telegraph, General Electric and Westinghouse and inventors – including Reginald Fessenden, Lee De Forest and Cyril Elwell – were also hard at work ideating about radio and mapping out ways to develop the potential of wireless communication and their contributions, among others, were important to making it possible to widely broadcast much more-sophisticated messages than the simple dots and dashes of Morse Code.

By 1914, Fessenden, a Canadian who was once employed in Thomas Edison’s labs, had worked with General Electric to build alternators that could sustain a consistent broadcast wave powerful enough to transmit voices and music over thousands of miles. Radio was even more deeply developed for its military applications in World War years of the first half of the 1900s.

In 1919, Marconi’s resources were sold to General Electric and with that Radio Corporation of America (RCA, which spawned NBC Radio) – led by former Marconi employee David Sarnoff – was formed. The radio boom began, as people found it indispensable for receiving news and entertainment programs. RCA’s stock price went from $85 in early 1928 to $500 by the summer of 1929. The stock market crash of 1929 dropped it down to $20 per share, but tough economic times of the 1930s couldn’t stop the well-developed NBC network. The development of a vast array of programming choices in the 1930s brought the “Golden Age of Radio,” and by 1939 nearly 80 percent of the United States population owned a radio.

In 1919, Marconi’s resources were sold to General Electric and with that Radio Corporation of America (RCA, which spawned NBC Radio) – led by former Marconi employee David Sarnoff – was formed. The radio boom began, as people found it indispensable for receiving news and entertainment programs. RCA’s stock price went from $85 in early 1928 to $500 by the summer of 1929. The stock market crash of 1929 dropped it down to $20 per share, but tough economic times of the 1930s couldn’t stop the well-developed NBC network. The development of a vast array of programming choices in the 1930s brought the “Golden Age of Radio,” and by 1939 nearly 80 percent of the United States population owned a radio.

Historical records show that Marconi would probably not have been successful had he not taken advantage of the inventions of Tesla and others to develop and implement his communications systems. For example, he was known to have used a Tesla oscillator to boost his gear enough to transmit the first signals across the English Channel.

In the case of radio, as with all breakthroughs in the development of human communication tools from the telegraph and onward, the truth is that many inventors made contributions to its creation, refinement and successful networking and distribution.

World Changes Due to Radio

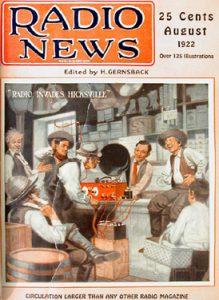

In the boom of the 1920s, people rushed to buy radios, and business and social structures adapted to the new medium. Universities began to offer radio-based courses; churches began broadcasting their services; newspapers created tie-ins with radio broadcasts.

By 1922 there were 576 licensed radio broadcasters and the publication Radio Broadcast was launched, breathlessly announcing that in the age of radio, “government will be a living thing to its citizens instead of an abstract and unseen force.”

As with television in later years, however, entertainment came to rule the radio waves much more than governmental or educational content, as commercial sponsors wanted the airtime they paid for to have large audiences. Most listeners enjoyed hearing their favorite music, variety programs that included comic routines and live bands, and serial comedies and dramas. Broadcasts of major sports events became popular as the medium matured and remote broadcasts became possible.

Radio was a key lifeline of information for the masses in the years of World War II. Listeners around the world sat transfixed before their radio sets as vivid reports of battles, victories, and defeats were broadcast by reporters including H.V. Kaltenborn and Edward R. Murrow. Franklin D. Roosevelt (at right), Winston Churchill, Adolph Hitler and other political leaders used the medium to influence public opinion.

Past Predictions About the Future of Radio

A Boston Post editorial from 1865:

“Well-informed people know it is impossible to transmit the voice over wires and that were it possible to do so, the thing would be of no practical value.”

Sir William Thomson, later Lord Kelvin, a Scottish mathematician and physicist, is quoted as saying in 1897:

“Radio has no future.”

A notice titled “Telegraphy Without Wires” in the Jan. 23, 1897, Scientific American, reporting on a demonstration of Marconi’s radio:

A notice titled “Telegraphy Without Wires” in the Jan. 23, 1897, Scientific American, reporting on a demonstration of Marconi’s radio:

“If the invention was what he believed it to be, our mariners would have been given a new sense and a new friend which would make navigation infinitely easier and safer than it now was.”

A May 7, 1899 review in the New York Times headlined “Future of Wireless Telegraphy”:

“All the nations of the earth would be put upon terms of intimacy and men would be stunned by the tremendous volume of news and information that would ceaselessly pour in upon them.”

According to a report in Dunlap’s Radio and Television Almanac, Sir John Wolfe-Barry remarked at a meeting of stockholders of the Western Telegraph Company in 1907:

“…As far as I can judge, I do not look upon any system of wireless telegraphy as a serious competitor with our cables. Some years ago I said the same thing and nothing has since occurred to alter my views.”

A June 1920 article in Electrical Experimenter titled “Newsophone to Supplant Newspapers” reported on an idea for a news service delivered via recorded telephone messages and also predicted the “radio distribution of news by central news agencies in the larger cities to thousands of radio stations in all parts of the world” leading to a time when “anyone can simply listen in on their pocket wireless set.”

H.G. Wells wrote in “The Way the World is Going” in 1925:

“I have anticipated radio’s complete disappearance…confident that the unfortunate people, who must now subdue themselves to listening in, will soon find a better pastime for their leisure.”

In 1913 Lee de Forest, inventor of the audion tube, a device that makes radio broadcasting possible, was brought to trial on charges of fraudulently using the U.S. mails to sell the public stock in the Radio Telephone Company. In the court proceedings, the district attorney charged that:

“De Forest has said in many newspapers and over his signature that it would be possible to transmit human voice across the Atlantic before many years. Based on these absurd and deliberately misleading statements, the misguided public…has been persuaded to purchase stock in his company…”

De Forest was acquitted, but the judge advised him “to get a common garden-variety of job and stick to it.”

The content on this page is an excerpt from Janna Quitney Anderson’s book “Imagining the Internet: Personalities, Predictions, Perspectives,” published by Rowman & Littlefield in 2005.

View history of other information technologies:

<Telegraph><Radio><Telephone> <Television> <Internet>