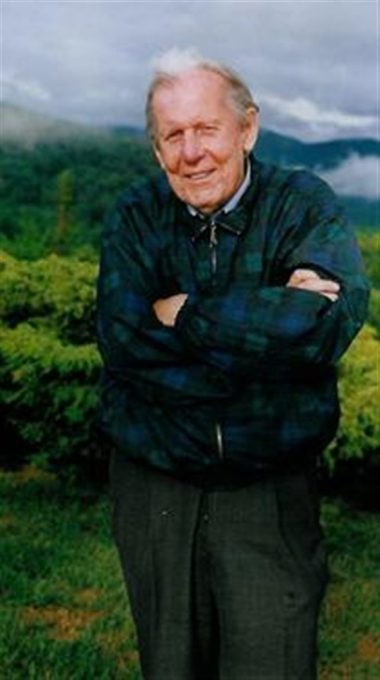

The Rev. Dr. Thomas Berry, a Catholic priest of the Passionist order and internationally recognized cultural historian, will receive an honorary doctor of humane letters degree from Elon University in a special ceremony March 17.

Berry, a native of Greensboro, N.C., will be honored at Elon’s Voices of Discovery lecture, scheduled for 7:30 p.m. in McCrary Theatre.

Berry, 93, who describes himself as a “geologian,” has focused his life’s work on the relations of humans with the cosmos and Earth. In 1989, Newsweek magazine described him as “the most provocative figure among the new breed of eco-theologians.”

“We have a moral sense of suicide, homicide, and genocide, but no moral sense of biocide or geocide, the killing of the life systems themselves and even the killing of the Earth,” Berry wrote in a Harvard seminar on environmental values in 1996.

At an early age, Berry concluded that commercial values were threatening life on the planet. In 1933 he entered the Passionist Religious Order and began examining cultures and their relations with the natural world.

Believing the wisdom of Asia indispensable for adequate learning, Berry went to China in 1948 to study and teach at Beijing’s Fu Jen University and returned to America in 1949 when Mao Tse-tung took over China. Subsequent studies in Chinese language and culture at Seton Hall University and Sanskrit and South Asian culture at Columbia University were interrupted by service as United States Army chaplain in Germany (1951-54). Afterwards Berry undertook a teaching career, first with the Asian Institute of Seton Hall University (1956¬-61); then with the Asian Institute of St. John’s University (1961-65); finally, at Fordham University (1966-79), where he instituted the doctoral program in the history of religions.

In 1970 Berry inaugurated the Riverdale Center for Religious Research in Riverdale, NY. From this base and with his presidency of the American Teilhard Society (1975-1987), Berry’s international influence as thinker, writer, and lecturer expanded rapidly. From around the world, scholars and others came to the Center for rethinking their disciplines in the light of newly understood relations of humans to Earth. In 1998 as part of Harvard’s international Forum on Religion and Ecology (FORE), the Thomas Berry Foundation was established by Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim, currently of Yale University.

Besides the 11-volume “Riverdale Papers” and treatises on “Buddhism” (1966) and “The Religions of India” (1971), the most influential of Berry’s books are “The Dream of the Earth” (1988, National Lannan Non-Fiction Award 1992); “The Universe Story: From the Primordial Flaring Forth to the Ecozoic Era” (1992) (with mathematical-cosmologist Brian Swimme); “The Great Work: Our Way Into the Future” (1999); and “Evening Thoughts: Reflecting on Earth as Sacred Community” (2006). Berry’s papers are housed in the Harvard University Environmental Science and Public Policy Archives.

Having returned to his native Greensboro in 1995, Thomas currently resides in Well-Spring Retirement Community where he continues work on further publication, notably “Religion in the Twenty-first Century.”

Berry’s connection to Elon has been through a long mentoring relationship with Andy Angyal, professor of English and a strong voice for environmental issues at Elon. Angyal has incorporated Berry’s work into his courses and promoted the university’s decision to honor Berry with the honorary doctorate.

Berry has received seven previous honorary doctorates and numerous other awards and honors, including the United States Catholic Mission Association Award, the 1992 James Herriot Award of the Humane Society of the United States, Honorary Canonship of the Episcopal Cathedral of St. John the Divine, the 1993 Bishop Carroll T. Dozier Medal for Peace and Justice, the Catholic University of America 1993 Alumni Research and Scholarship Award, and the 1992 Prescott College Environmental Award.

Elon’s honorary degree will be conferred by President Emeritus Earl Danieley, and will be accepted by Berry’s niece, Ann Berry Somers, a member of the biology faculty at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

Following the ceremony, the Voices of Discovery lecture will be given by palaeoclimatologist William Ruddiman, professor emeritus at the University of Virginia. His talk, titled “Farmers First Began Altering Global Climate Thousands (not Hundreds) of Years Ago,” proposes that atmospheric greenhouse gas levels were first affected by early agriculturists through deforestation and the tending of livestock. His ideas suggest a more basic and significant impact of human activities on global climate than has been previously believed.

The event is free and open to the public.

In connection with this honor, Fr. Berry has written the following letter to students:

“A Letter to Students”

By: Thomas Berry

My basic advice to you is to keep a clear awareness that you are living in the transition period between the 20th and the 21st centuries. Your generation will be taking the first steps toward a new context for our human lives after the creativity and the destruction caused by the 20th century.

Above all you need to remember that the human community is an integral member of the Earth community. Earth is our basic guide in every aspect of our lives. Earth provides the air we breathe, the water we drink, the food we eat, the land we walk on. The list could go on and on even to the awakening of our human understanding and our creation of language. Earth and the universe beyond is our most profound source of understanding.

As children we need to experience the dawn and the sunset, the fields and the woodlands. We need to hear the songs of the birds, to see and hear and touch the various forms of animal life. We need to feel the wind and the rain. This is all our primary education. It shaped the early civilizations of all the peoples of the world as we built our homes, our cities, our countries, had our deepest thoughts, and wrote our profoundest literature.

Then, some centuries ago, we began our modern sciences. Gradually we obtained a certain limited control over the natural life systems. We assumed that we knew how life functions. We obtained a certain control over life functioning. We thought that we could make the natural world responsive to our least human needs and wishes. We thought that we knew more than we really knew. This illusion of human intelligence took place most extensively in the 20th century, the century through which I have lived.

Toward the end of that century, just when your generation came on the scene; a sudden awakening took place. You will be hearing and reading about the difficulties, especially the social and economic difficulties suddenly revealing themselves, difficulties from excessive heat and the melting of the glaciers, the lack of rainfall throughout the woodlands. Despite massive increase in numbers, the automobile has only a limited future as its energy supply is progressively exhausted.

While there is no need for anxiety concerning the future, there is need for a careful rethinking of our human situation and the limitations in the scientific use of the natural world. You will need the sciences to recover from the unwise use of the sciences. We cannot do without the guidance they offer, but we must be clear that they cannot replace the natural life systems.

Your basic source for understanding is Earth, our way into the universe itself. This experience of Earth comes to us in two forms: an earlier form in the indigenous and classical periods of thought development; and the second, that of the scientific development of the last five hundred years of mainly Western cultural development. These later forms need to function within the context of the earlier forms, which gave us our concepts of value and meaning, our interpretation of life, which the sciences of themselves can never develop.

Thus when the sciences function without the context of the earlier interpretations of life, they become destructive. Operating within this context, they become a wisdom.