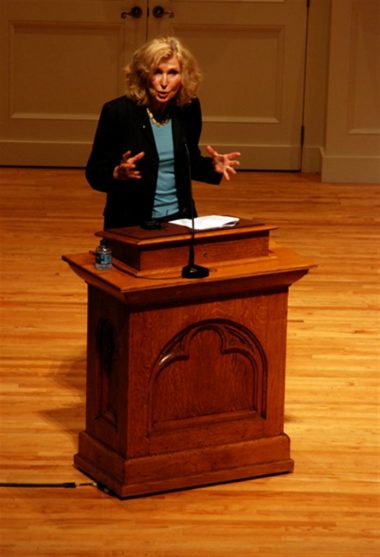

Jurate Kazickas felt shrapnel tear through her legs and face during the Battle of Khe Sanh and dug her own foxhole in the Vietnamese jungle. But in Whitley auditorium Thursday afternoon she told the audience of Elon students and faculty that it doesn’t matter if a war reporter is male or female—bombs don’t discriminate.

She had quit her former job at Look magazine when supervisors refused to send her to the war-torn jungle as a correspondent.

“It was the biggest story, it was the only story, it was on all the front pages,” she said. “It was my generation and it touched everybody.”

Kazickas talked about the laxity of press regulations and lack of restrictions in Vietnam. She claimed that once someone got a press pass Vietnam, they were free to roam the country.

This freedom led to the war’s end, as reporters saw the inaccuracies and falsities U.S. officials reported to a worried American public, she said.

Kazickas wrote several stories, including those about the brokenhearted soldiers who received “Dear John” letters and some “hometown” articles that profiled specific soldiers and their remarkable experiences.

“The entire country was available to write about,” Kazickas said.

As a woman during war time, Kazickas found herself dealing with century-old gender stereotypes.

Platoons wouldn’t let her march with them, claiming she couldn’t keep up, and she had to contend with generals who saw her sex instead of her skill. She had to fight hard to be seen as a female journalist and not just a female.

She repeated the statement she told so many uncooperative military men: “I have my press pass and you can’t say no.”

Kazickas emphasized the importance of journalists in a world where war seemed a constant reality.

“We have to go to forgotten places, write about forgotten people and forgotten issues,” she said. “We need to broaden the human consciousness.”

She discussed trailblazers who pioneered the field of female war correspondents. She said women covering war had to fight on two fronts — against their editors and against U.S. military policy that prevented women from going into combat zones.

Editors and policy makers alike claimed war was too dangerous, women would be a distraction to the soldiers, and they would not have appropriate latrine facilities in a war zone.

“They [women journalists] were ambitious, curious and adventurous,” she said after listing those obstacles placed in female reporters’ way. “And nothing was going to stop them.”

Kazickas’s experiences in Vietnam — watching young men die, hearing the false reports broadcasted from Saigon — were scarring.

“It just sears your soul forever,” Kazickas said. “The in and out of death just killed me.”

She said the most important question reporters must ask themselves before becoming a war reporter is if the story is worth their lives.

“A dead journalist,” she said solemnly, “can’t write anymore stories.”

By Margeaux Corby, ’10