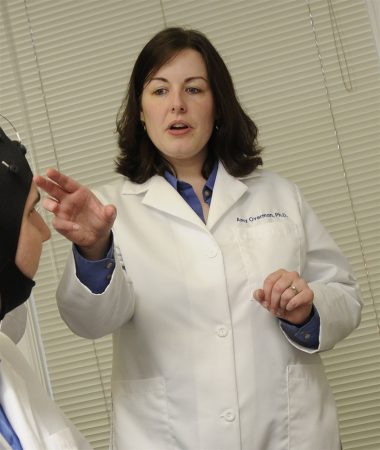

If the maker of Big Red and Juicy Fruit thinks its chewing gums have a monopoly on boosting your memory, it should think again. New work by Elon University faculty member Amy Overman and her undergraduate researchers show that gum itself isn’t special – any candy or oral activity probably works just as well at sharpening the mind.

Overman’s work appears in next month’s print edition of Appetite and is currently featured online. Her article, “Chewing gum does not induce context-dependent memory when flavor is held constant,” builds upon previous research. As Overman and her students discovered, despite plenty of work by scholars in recent years to study the effects of chewing gum on cognition, no one ever held the flavor steady.

In this case, that flavor was cinnamon. Researchers used 101 student volunteers to test whether chewing cinnamon gum versus sucking on a cinnamon candy helped participants remember sets of words they first viewed minutes earlier. The results? The only difference noted was students’ ability to better remember concrete words – like “plate,” “star” and “lock” – than abstract words like “luck,” “mood” or “aim.”

That’s nothing new. It did, however, prove to Overman and her students that their test was a solid measure of memory ability. Elon students Justin Sun, Abbe Golding and Darius Prevost co-authored the research.

“I think it’s just the action of your mouth that serves as a memory cue,” Overman said. “It has nothing to do with the gum itself. Flavor could also be playing a role. When you chew gum you aren’t just switching from doing nothing to chewing, you’re also switching from having no flavor to having a strong flavor, right next to your nose.

“It is well known that scents are strong memory cues. Flavor is mostly made up of scent,” she said. “That is why our study kept flavor the same in both conditions, to rule out flavor’s ability to influence memory and just look at how mouth movements were influencing memory.”

Anything unique will help make a memory more accessible later so moving your mouth, whether sucking or chewing, can form a memory cue, Overman said. A special flavor can form a memory cue. Also, sucking or chewing could act as a stress reliever, like working a “worry stone” but in a person’s mouth instead of his or her hand.

Overman joined the Elon faculty in 2007 and has focused her research on relationship between aging and memory, notably the neurological aspects of that relationship. The Pennsylvania native earned her master’s and doctoral degrees from the University of Pittsburgh and the Center for the Neural Basis of Cognition.

To read the full study, click on the link to the right of this page under the E-Cast section.