Leaders in law and legal education shared insights about one of the nation’s most significant civil rights attorneys at Elon Law’s 2014 Martin Luther King, Jr. forum.

“Few other lawyers in North Carolina, indeed in the United States, have had such a profound influence and impact on the progress of justice and the advancement of justice and civil rights as did Julius Chambers,” Johnson said. “So it is important to recall his contributions, particularly at a time when much of what Julius and Martin Luther King and Franklin McCain gave their lives to, seems under assault, attack and threat in these turbulent times.”

Elon Law professor and former North Carolina Supreme Court chief justice James G. Exum, Jr., who organized the event with Elon Law professor Eric Fink, introduced the forum’s panelists. They included:

- John Charles Boger, Dean and Wade Edwards Distinguished Professor of Law at the University of North Carolina School of Law. Boger worked with Chambers at the UNC Center for Civil Rights and previously at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF).

- James E. Ferguson II, named one of the nation’s top ten litigators by the National Law Journal and a founding partner with Chambers of the firm now named Ferguson Chambers & Sumter, P.A.

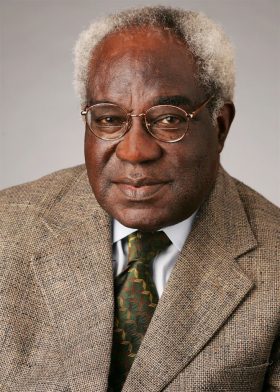

- The Honorable Henry Frye, former chief justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court, a member of Elon University’s law school advisory board and a contemporary of Chambers who graduated from UNC School of Law in 1959, the year Chambers began studying law there.

- Geraldine Sumter, partner at Ferguson Chambers & Sumter, P.A.

The forum was moderated by Jonathan R. Harkavy, partner at Patterson Harkavy LLP and 2013 recipient of the North Carolina Bar Association’s H. Brent McKnight Renaissance Lawyer Award. Harkavy opened the discussion with a quotation by Martin Luther King, derived from an insight of transcendentalist Theodore Parker, that “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

“Today, we are honoring the life of someone who bent that arc toward justice and that someone is Julius Chambers,” Harkavy said referencing the scope of impact that Chambers’ legal advocacy has had over decades.

The LDF website summarizes some of Chambers’ legal achievements as follows:

“Over his years in practice at the firm [Ferguson Chambers & Sumter, P.A.], and later at LDF, Chambers litigated and argued landmark civil rights cases in the United States Supreme Court, including Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) (school desegregation), Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986) (voting rights), Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) and Ablemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975) (employment discrimination), Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. 899 (1996) (redistricting), among many others.”

At the Elon forum, Justice Frye noted that Chambers excelled academically, graduating summa cum laude from what is now North Carolina Central University and first in his class at UNC School of Law, where he served as editor-in-chief of the law review. Frye explained what sparked Chambers to pursue a legal career.

“Julius’s father was a mechanic who owned his own shop and he did some work for a person and the person would not pay him,” Frye said. “His father decided to get a lawyer to sue this person, who happened to be white, and he had trouble, in fact he never did find a lawyer in the town who would file a law suit for him. So the credit is given to that for Julius deciding that, ‘I’m going to be a lawyer one day.’”

Mr. Ferguson, while noting that Chambers established one of the highest records of success in cases before the U.S. Supreme Court, said Chambers did not seek to make history or a name for himself through his work, but rather to help individuals pursue justice.

“Chambers was a man with a mission, but not always a plan. He knew that he wanted to devote his life to correcting the ills of society that plagued his family, that plagued him and that plagued many, many other people,” Ferguson said. “But he didn’t one day sit down and map all of this out, and say, well, in the year 1968 I’m going to reopen the Swann case, and then in the 1970s I’m going to do the Griggs case and the Moody case, and then in the decade of 80s I’m going to do the Gingles case and voting rights. He never sat out to make a name for himself. It was never intended to bring recognition to Julius Chambers. What it was intended to do was not only to help folks, but to make sure that folks like his father, who couldn’t get legal representation, would get legal representation. If someone came to him with a problem and he thought he could help, he would take on that case irrespective of who it was, what it might pay or the complexity or simplicity of the legal issues, because he was just moving to help folks and he never ever lost that.”

Sumter provided a series of personal insights about Chambers, noting that he visited his mother almost every day when she became ill later in life and that he attended church every Sunday, wherever he lived, often working on legal matters prior to and after church. Sumter said that Chambers’ parents, William Lee and Matilda Alma Chambers, had an influential role in his life.

“Periodically Mr. and Mrs. Chambers would come down and sit in the lobby [of the law firm in its early days] and then when the clients had gone, would go into Chambers office and close the door and talk to him to be sure that he was paying attention to his clients and treating his clients right,” Sumter said. “He always respected and revered his parents.”

Boger noted that Chambers became Director Counsel of LDF following two historic figures in American civil rights law and history, Thurgood Marshall and Jack Greenberg. Then an attorney with LDF, Boger said he was eager to learn more about the man who would follow in their footsteps.

“What I knew was that [Chambers] had already argued and won what was the leading school desegregation remedy case … and two of the leading Title Seven cases,” Boger said. “He tried these cases in the trial courts, court of appeals, one them in the Supreme Court. Swan Mecklenburg was a nine-zero opinion with a very conservative chief justice. He was also litigating some of the leading voting rights cases in the country.”

Boger highlighted Chambers’ vision, determination, humility and care for others among some of his greatest traits.

During a question and answer period, Ferguson said that some of Chambers’ best legal skills included intensive preparation, issue identification and a unique advocacy style that relied in part on quiet oratory and engaging narrative.

“Judges leaned in to hear what he had to say,” Ferguson said.

Recurring themes in the reflections offered about Chambers at the Elon Law forum were that he valued people, lived with humility and worked zealously on behalf of his clients.

“I enjoyed the panelists’ discussion, remembrance and tribute of Mr. Julius Chambers,” said Elon Law student Adam Hunter L’16. “His courage, leadership and persistence – even in the face of violence – is what I will remember the most about this great civil rights leader. I’m glad Elon Law was able to have an event that gave us some historical insight to supplement our legal education.”

Remembrances of Chambers are available through the following links:

“Julius Chambers, a Fighter for Civil Rights, Dies at 76,” New York Times, August 6, 2013

“Julius Levonne Chambers In Memoriam” LDF

“Julius LeVonne Chambers…A Legacy of Service, Love and Commitment” Ferguson Chambers & Sumter, P.A.

The Elon Law forum was cosponsored by the Elon Law student chapter of North Carolina Advocates for Justice and the Elon Law Black Law Students Association.