When Toorialey Fazly ’14 left Afghanistan in 2010 to come to Elon, he was expecting the experience to be uneventful. What Fazly, who graduates this spring from the university, found instead transformed his life.

The sounds of rocket-propelled grenades and automatic rifles were commonplace for Toorialey Fazly.

Throughout his life, the land he called home had been torn by violence, first due to a Soviet invasion that lasted almost a decade and later by a brutal civil war caused by local warlords hungry for power, which led to a NATO and U.S. intervention in 2001. It was a reality most Afghans could not escape, and one that took some time for Fazly to leave behind, even when he was thousands of miles away in a small American town attending university. There were nights during those first transition days when the smallest of sounds woke him up. He would listen quietly, ready to grab the knife he kept next to his pillow at his off-campus apartment. It was the only weapon he had. It was the environment he was raised in.

But that was four years ago. Dozens of eye-opening experiences later, Fazly is getting ready for a new life after college. He graduates May 24 with degrees in economics and international studies (with a concentration in the Middle East) and a new perspective on life. For what started as just a college stint became a life journey that has touched him—and those around him—in unexpected ways. “If I summarize all my four years in a few words, I was living in a paradise,” Fazly says in a confident English that still contains the traces of an accent. “It might sound like an exaggeration, but from what I’ve lived with, these four years have been about education—and a paradise.”

✹ ✹ ✹

Despite all the uncertainties that surrounded him throughout his life, Fazly never let fear define him. On the contrary, he has defied it all his life. He defied it after his father fell sick when he was only 17 years old, forcing him to become the provider for his mother and younger siblings. He defied it when he left behind everything that was familiar for a chance to gain an education in the United States and then again once here, when a freak accident almost took his life. “There is one philosophy that helps me with every problem in life,” Fazly says. “If I face a problem, I tell myself, ‘This is not the end of the world, this is not the dark night that you are living. Tomorrow there will be a bright day for you. Just be patient.’”

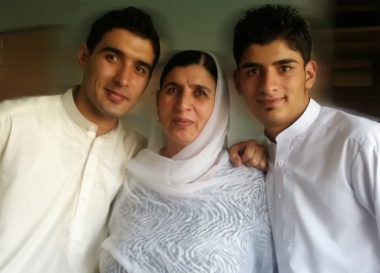

He never doubted that one day he would attend an American university. In fact, he had been working for that opportunity since an early age, though it didn’t come easy. After the death of his father, Rahmuddin, Fazly considered leaving school to start working, something his mother, Raqiba, wouldn’t allow. “It doesn’t matter how much we suffer, I don’t want you to leave learning, leave school,” he remembers her telling him. “Finish your education; education is key.”

And so he divided his time between school and work. He attended classes until noon and worked the rest of the day doing whatever was available—sorting almonds, painting houses. Throughout his middle and high school years, whenever schools were closed due to political unrest, his mother arranged for him to take private English classes and made sure he attended regardless of the circumstances. He remembers one particular day, when he was in the sixth grade. He and a friend were returning home from English class when they heard the sound of bullets hitting the concrete wall they were walking alongside. They immediately hit the ground and hid in a ditch. When they got up, they discovered the body of a woman who had been walking just steps in front of them. The sight of her white dress covered in blood still haunts him. He was crying when he got home. His mother consoled him and sent him to school the next day.

Looking back, Fazly appreciates his mother’s determination, for it was his knowledge of the English language that helped him land a job after high school with an American company that provided law enforcement training to the Afghan police. The position led to a job as the scheduler for the president of Afghanistan. By that time, Fazly had started taking classes at Kabul University and was looking for opportunities to go West. A trip to Washington, D.C., as part of his government job finally opened the door he had been looking for. Through a series of fateful encounters, Fazly found out a North Carolina school named Elon University was interested in admitting Afghan students. He applied and eventually received the Pavlov Endowed Scholarship, which is awarded to international students.

But the admission process wasn’t easy. Susan Klopman was Fazly’s first contact at Elon. Then vice president of admissions, she worked with him to get all his paperwork ready before he arrived in the country. It was post-9/11, which meant new regulations and hurdles to jump. “We were admitting a student from a country whose background was very difficult to verify,” she recalls. “I kept putting myself in his place. I’ve never mastered a second language, been alone in another country, suffered financial constraints, been uncertain about my future.”

She decided to take a chance on this young man who, though older than most first-year students, was so intent on learning. Four years later, she is still happy she did. “It was a learning experience,” she says. “He’s enormously brave to have done what he did, but he’s also an inspiration. He was willing to risk so much for an education.”

It didn’t take long for people to discover Fazly was not a typical high school student, says François Masuka, who works with international students at Elon. He had world experience; he had been in the world of grown-ups. He was organized and more independent than regular students. He was older and didn’t need much assistance. And so he was placed in a nearby apartment complex where he could have more privacy. Little did anybody know that decision was going to play a part in one of Fazly’s greatest challenges during his time at Elon.

✹ ✹ ✹

Only 15 days after arriving on campus, Fazly was riding his bike to class when he was hit by a car. He was taken to Duke University Hospital by helicopter with a broken neck and leg. Masuka was one of the first people to meet him at the hospital. “Usually, someone who was hit and had a broken vertebrae is in a panic,” he says. “But what I found is a relaxed patient. He was not under medication at the time. He was reassuring us that everything was OK. That’s not something you usually see in students.”

For Fazly, there was no other alternative but to be courageous and rely on his faith. There was no bitterness, no resentment. “I’m a big believer in God, so I know God has always helped me and no matter what, he would be with me all the time,” he says. “It was not easy but I knew I would be fine, that I would be walking again. I knew that.”

That certainty allowed him to cope with the countless doctor visits and procedures that followed. It also led him to the decision not to tell his mother about the accident until he saw her face to face; he knew there was nothing she could do except worry. When he went home that summer, he told her everything. He showed her a file with all his medical records. He showed her the X-rays and other reports detailing how they put screws on his head so he could wear a halo. She didn’t say anything, only cried. She was angry. The next morning, she thanked him for keeping the news from her.

Fazly not only survived the accident. He thrived after it. Before coming to Elon, he didn’t care if people liked him. The devoted Muslim expected to encounter distrust or even hatred. Whatever happened he was determined to finish his degree and make one or two friends along the way. What he didn’t expect was the level of love, attention and care he received. “The Elon community became my family,” he says. “It became my second home, a beautiful home away from home.”

Fazly adapted well to Western culture, and to Elon’s in particular, says Carolynn Whitley, who works in the department of political science, where Fazly has spent countless hours in the past four years as a student, office worker and research assistant. He embraced differences. He welcomed interactions with people from different races, faiths, ethnicities and countries.

Phil Smith, then with the chaplain’s office, saw this firsthand as the two worked closely to provide more programs to Elon’s growing Muslim student population and as they developed more interfaith opportunities. He was the first student to apply to the Better Together multi-faith living-learning community. He was paired with Mason Sklut ’14, epitomizing what the community was all about, Smith says—a Muslim from Afghanistan and a Jew from Charlotte, N.C., who lived together and learned from each other across and in spite of perceived cultural and religious boundaries.

All those interactions taught Fazly valuable lessons. “They opened my eyes to see everything that I come across from a different perspective than the one I had before,” he says. “The education that I’ve received from Elon changed my whole life and it put me on a different track.” He even met the woman he will marry through Elon while studying abroad in London last spring, something that brings a smile to his face.

✹ ✹ ✹

Some might say Fazly got lucky. But if you ask him, he would tell you luck had nothing to do with it. Everything happens for a reason; nothing is coincidence. Everything happens through hard work, if you are willing to seize the opportunities that come your way. “I believe that God gradually brightens up every morning, that God shows us a way to succeed and a way to victory,” he says. “My life has been like that as well.”

His positive attitude has left an indelible mark on those with whom he has come in contact. He taught Masuka to be young at heart, not to worry too much or want to be in control of everything. Sometimes you have to let things go, Masuka says, and something good will come out of it. Klopman, on the other hand, has learned to not let fear control her, to boldly take the challenges ahead. “It’s been a great friendship and I can’t wait to see what the future unfolds for him,” she says.

Fazly, too, is looking to the future. He already has a job after graduation but longs to return to his country, just not right now. Things are uncertain for a person in his position—with ties to the previous government, educated in the West, looking for a unified Afghanistan. Still, he remains optimistic that the recent elections are a sign democracy will prevail and Afghans can build on the few but priceless achievements from the past 12 years, with the support of the international community. He sees himself working for an international organization or for his country in 10 years, living with his family in a house they can call their own, but above all, helping anyone who needs a hand. That’s just how he was raised. Even when things were tough at home, he managed to help those less fortunate than him.

“If I did it with empty hands, with full hands I could do it better.”