The recent addition of a solar farm to the far southeast corner of campus is only the latest feature of a site used by Elon students and professors to learn, teach, research and serve the broader Alamance County community.

You pass it on your way from campus to downtown Burlington and, until this spring, it might have been easy to overlook. Just beyond Magnolia Cemetery, almost within sight of the intramural fields on South Campus, is a part of campus that for the past three years has featured a small greenhouse, shipping containers converted into an indoor work space, garden plots and a row of apple trees.

You pass it on your way from campus to downtown Burlington and, until this spring, it might have been easy to overlook. Just beyond Magnolia Cemetery, almost within sight of the intramural fields on South Campus, is a part of campus that for the past three years has featured a small greenhouse, shipping containers converted into an indoor work space, garden plots and a row of apple trees.

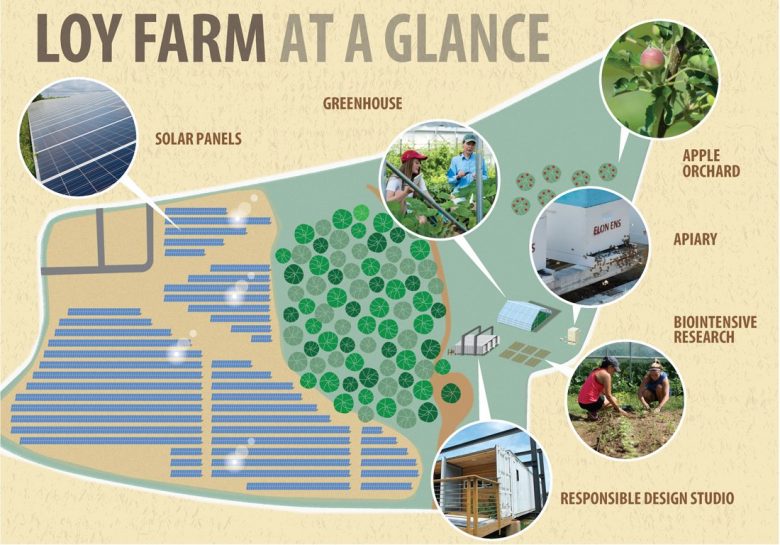

As of this summer, that land is a lot harder to miss. Just look for the thousands of solar panels that mark the start of Loy Farm, one of Elon University’s fastest-growing resources for hands-on learning, academic research and community engagement. If you ask students, faculty and staff what makes it unique, they don’t point to any one component but rather the interplay of the resources there. “It’s not just this ‘thing’ that Elon does,” says Elaine Durr, Elon’s director of sustainability. “The research and work on the farm have implications not only in our local community, but in the communities where our graduates live and work.”

The farm on Front Street used to be fields of tobacco, wheat and corn. With the assistance of longtime Elon benefactor Bill Loy, university leaders in 2000 purchased what was once the Loy family homestead. The purchase agreement had given landowner Keith Loy, Bill’s older brother, lifetime rights to the property, and when Keith died in 2006, faculty and staff started to envision educational and research opportunities on the property.

Garden plots and a greenhouse now serve as resources for food production related courses. The farm itself is a critical component of the university’s Peace Corps Prep Program. It also offers learning opportunities for community groups and programs such as the Elon Academy, whose students visit the property each summer to discover opportunities for starting their own gardens.

“We’re really trying to provide a model to show a new way of how we can live, where we can live and where our food comes from,” says MacFall, director of Elon’s Center for Environmental Studies, which oversees the farm. “And we want Elon to be a leader in civic engagement.”

To that end, MacFall is now leading a new effort to better connect local farmers with the university, grocery stores and restaurants that sell North Carolina produce. Her work is funded in part by the N.C. Department of Commerce, and it includes workshops being planned at Loy Farm for local growers to learn about sustainable practices that can bolster crop yields. Elizabeth Zander with the Piedmont Conservation Council, which is partnering with MacFall on the project, says the farm demonstrates you don’t need to have many acres to be a successful farmer. “Students and community members who work on the farm also gain a greater appreciation for the work that goes into producing food and the importance of sustainable techniques for protecting our soils and waterways,” she adds.

Ongoing research also includes garden plots using “grow biointensive” organic practices. Designed by Steve Moore in the Department of Environmental Studies, a de facto farm manager for the site, the research is vital to students who take part in the Peace Corps Prep Program he coordinates because of its usefulness in developing countries where food and resources are often scarce.

The farm is already shaping the career paths of several young alumni, including Rebecca Berube ’12, an education assistant and social media coordinator at Azuero Earth Project in Panama, who was part of the farm’s early development and helped establish the original garden plots.

Max Potember ’14 was also inspired by his time at the farm. He joined with classmates before graduation to plant a small orchard featuring several varieties of apple trees. He today works as an environmental soil scientist at Geo-Technology Associates, Inc., in Maryland, and credits skills honed at Elon for his early professional success.

When he is not in the classroom, Associate Professor Robert Charest oversees a studio at Loy Farm designed and built by merging four shipping containers into a single space. Several of his students are now using that space to design and build prototypes of “microhouses,” some as small as 50 square feet with the goal of impacting the environment as little as possible. “What we’re doing that’s phenomenal is looking at land use through architecture and design, and putting it right next to the other big challenge, which is food production,” Charest says. “It becomes a microcosm for all of the challenges to come with sustainability in the developing world.”

“Knowing that sometimes the only meal someone gets a day is from us, we’re mindful and conscious about fresh produce, wellness and health benefits,” says Jan Bowman, program director at Allied Churches. “Many of our guests suffer from diabetes and obesity. If we can serve them a product that is nutritiously sound, maybe they’ll take things from that.”

Then there’s the solar farm that soon begins operation on the land. Nearly 10,000 photovoltaic panels installed earlier this year will generate enough electricity to power about 415 homes serviced by Duke Power. The university is leasing the land to a private company that owns the panels, though students will have the opportunity to study the equipment, operation and economic model.

What’s next for Loy Farm? In its updated Sustainability Master Plan, the university outlines the hiring of a full-time manager to oversee operations, which will allow the farm to expand production from three to five acres. If the university were to build a handling facility that met specific federal food safety guidelines, the additional food could be used in campus dining halls and further boost contributions to Allied Churches.

Thus, there might be even more opportunities for students and professors to collect squash bugs in a greenhouse used to train future Peace Corps volunteers harvesting vegetables to feed the hungry in a county with hundreds of homes powered in part by a campus solar array.

Moore certainly hopes so. “Because of this farm, things start to move outward,” he says.

From Loy Farm to the Peace Corps

The Peace Corps Prep Program was started in 2013 to teach participating students about sustainable agriculture, responsible architecture and environmental management. “Our prep program synchronizes with the foundational mission of the university to produce global citizens,” says Steve Moore, a faculty member in the Department of Environmental Studies and coordinator of Elon’s Peace Corps Prep Program. “I believe it’s the epitome of that mission.”

Two students in Elon’s Class of 2015 who took part in the program, Elaina Vermeulen and Emily Mount, depart soon for assignments in Guatemala and Fiji, respectively. A third alumnus of the program, Lorne Paterson, is interviewing with the Peace Corps. “This program has given me an understanding of different aspects of projects I could lead,” says Mount, an environmental science major from Boston. “Loy Farm gave me an appreciation for working with my hands, and realizing that’s what I want to do.”

While the program does not guarantee a placement with the corps, students gain skills that are an advantage in the application process and in other international development work. Many instructors use Loy Farm to offer that hands-on instruction.

For Vermeulen, an international studies major from Sterling, Mass., time at the farm provided her with the tools and resources she needs to help address hunger on a global scale. “I’m fortunate,” she says. “I owe all of that to Loy Farm. I owe that to Professor Moore. I owe that to Elon.”

By Eric Townsend