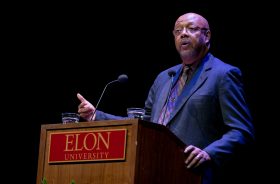

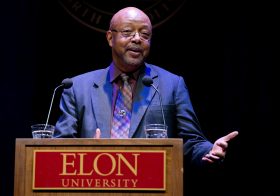

Miami Herald syndicated columnist Leonard Pitts Jr. delivered the 2015 Baird Pulitzer Prize Lecture on Thursday night where he shared insights about race, “personal responsibility” and how to foster social justice for all people.

For Pulitzer Prize-winning syndicated newspaper columnist Leonard Pitts Jr., the story of Ahmed Mohamed is a classic case of white American “innocence.”

For Pulitzer Prize-winning syndicated newspaper columnist Leonard Pitts Jr., the story of Ahmed Mohamed is a classic case of white American “innocence.”

A few weeks ago, the 14-year-old Mohamed brought a homemade clock to school in Irving, Texas, to impress his engineering teacher. When another teacher later that day saw the same clock after it beeped from inside an old pencil box, concluding that the clock may have been a “bomb,” Mohamed was interrogated for hours by police without his parents present.

“Despite what they have since said, no one in authority thought Ahmed had brought a bomb to school,” Pitts told a crowded McCrary Theatre on Thursday night for Elon University’s 2015 Baird Pulitzer Prize Lecture. “When you see a bomb, your first step is not to call administrators. Your first step is to get the hell out of there, and tell everyone to do the same.”

Though police never filed charges, Mohamed was suspended from school for three days “apparently, just because.” And when Irving Police Chief Larry Boyd was asked whether the whole incident was handled in such a fashion because of Mohamed’s Islamic faith and the color of his skin, the city’s top cop denied the possibility.

“That denial has become part of the ritual, the accepted script we follow for incidents like this,” Pitts lamented in his “Race in America” presentation.

Mohamed’s ordeal illustrates an ongoing American insistence – particularly white America’s insistence – of its own racial “innocence,” Pitts continued. So often in today’s culture, Americans will affix “personal responsibility” on minorities to defend or deflect blame for prejudicial and, at times, deadly treatment. There is almost never an acknowledgement from a majority of white Americans that racism remains a very real threat to minorities.

Pitts quickly listed several examples of white American denial, some of which were drawn from his own life, and others from high-profile stories that have made national news over the years.

Pitts quickly listed several examples of white American denial, some of which were drawn from his own life, and others from high-profile stories that have made national news over the years.

There was Pitts being questioned in college about a missing bicycle when white classmates were ignored. Why? Because at University of Southern California, situated in an area of Los Angeles with high crime and a large black population, he should just accept it. A few years later, Pitts was ordered from his car by a police officer using his cruiser’s loudspeaker and then drawing his gun as Pitts exited – all for a smoking tailpipe.

There was Rodney King beaten on camera in 1991 by four Los Angeles police officers. There was Trayvon Martin killed in 2012 for wearing a hoodie as he walked through his own neighborhood. There was Martin Lee Anderson killed in a Florida juvenile detention center when guards used physical brutality, including the forced inhalation of ammonia, against the 14-year-old when he stopped exercising due to exhaustion.

President Barack Obama has been called a terrorist, compared to a chimpanzee, described as “uppity” and yelled at during his State of the Union. What happened after Pitts called attention to these insults and attempted to hold others accountable?

“Readers told me I was only saying these things and making this defense because I am a racist and only support the president because he is black,” Pitt said. “‘Innocence.’”

Pitts pointed to a psychological need all people have to deflect responsibility for actions that harm others. It’s not that all whites are overt racists. On the contrary, he said. Many white people mean well but they don’t speak up to at least acknowledge problems that affect people of color.

“There is in all of us a very human desire, a need to feel good about ourselves, about who we are and where we are from,” Pitts said. “Nobody wants to look in the mirror and see a bad person looking bad. If you can’t claim innocence, are you supposed to claim guilt?”

It’s also trendy among conservative groups in 21st century America to cite “personal responsibility” for what harms other people. Rodney King “should have stopped moving.” Trayvon Martin “shouldn’t have been wearing a hoodie in the rain.” When it comes to social woes that impact black families – higher numbers of out-of-wedlock births, absent fathers, higher school dropout rates – if African-Americans took more “personal responsibility,” those issues would disappear.

“I’m fine with personal responsibility and I’ll tell you something many of you may not know. Most African-American people are,” Pitts said. “I have almost never been criticized by an African-American person for pointing out that African-American people have some work to do in this equation as well.”

Which brought Pitts to his advice for white Americans.

“What do you do if you are decent and white? What is your role? What is your place in this new era of anger and activism?” Pitts said. “Maybe you cannot march. Maybe you have no money or celebrity to give. But you can see. And you can let it be known that you can see.”

Stand with minority groups in their own quest to be heard, he said. One of the most powerful moments for Pitts following June’s mass shooting in a black Charleston church was seeing a large crowd of white people marching through the city, chanting “black lives matter.”

“I don’t know that I have the words to explain to you how good that video was for my soul,” he said. “Indeed, it would not be too much of an overstatement to say I loved those white sisters and brothers in that moment for what they did.”

A former writer for Casey Kasem’s radio program “American Top 40,” Pitts was a pop music critic at the Miami Herald where he began writing about race and current affairs in his own column. Today, his Miami Herald newspaper column on pop culture, social issues and family life is syndicated in more than 150 daily newspapers.

In 2002, Pitts won the top prize for commentary in the Scripps Howard Foundation’s National Journalism Awards program for a collection of entries, including those following the World Trade Center terror attacks. Two years later, was he was honored with a Pulitzer Prize for the same column.

Pitts’ column has won awards from the Society of Professional Journalists, the National Association of Black Journalists, the American Association of Sunday and Feature Editors and the Simon Wiesenthal Center, among others. He is a three-time recipient of the National Headliners Award.

His most recent novel, “Grant Park,” will be released in October and covers four decades of race relations in the United States. He is also the author of the bestseller “Becoming Dad: Black Men and the Journey to Fatherhood,” a poignant account of the nature and meaning of black fatherhood in the contemporary United States. Several other books have won him acclaim as well.

Pitts joked about his experiences visiting Elon University. During his last appearance on campus, his son was hours away from welcoming Pitts’ granddaughter into the family. On Thursday night, it was his daughter’s expected delivery of another granddaughter that kept him waiting.

“If I get a tweet, it’s going to be because my daughter is going to pop any minute,” he said. “I don’t know what it is about Elon and grandbabies, but every time I come here, I seem to be the recipient of a granddaughter. It’s pretty cool, really!”

The Pulitzer Prizes, awarded annually since 1917, are the nation’s most prestigious awards in journalism and the liberal arts. The Baird Pulitzer Prize Lecture Series brings recipients to campus each year with guests who have included Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn, David McCullough, Dave Barry, George Will, Anna Quindlen, Thomas Friedman, Taylor Branch, David Halberstam and Maureen Dowd.

The Baird Pulitzer Prize Lecture Series was made possible in 2001 with an endowed gift from James H. and Jane M. Baird of Burlington, N.C., who were the first presidents of the Elon Parents Council. Their son, Macon, is a 1987 Elon graduate and their son-in-law, Michael Hill, earned his Elon degree in 1989.

Associate Professor Jeffrey Coker, director of the Elon Core Curriculum, thanked the Bairds for their gift during his welcoming remarks.

“I’d like to offer a sincere thank you to the Baird family, a treasured part of the Elon community. Your generosity allows great events like this one to happen,” Coker said. “On behalf of everyone in the room, I want you to know that you’re very appreciated.”