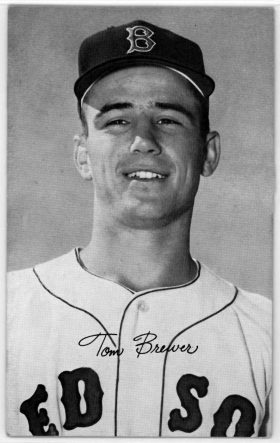

An infielder turned pitcher, Tom Brewer translated the lessons he learned during a semester spent at Elon in 1951 into a successful Major League Baseball career.

By Conor O’Neill ’11

By Conor O’Neill ’11

The path to becoming an All-Star pitcher for the Boston Red Sox and a good friend of baseball legend Ted Williams brought Tom Brewer through Elon College in the spring of 1951. It was there Brewer refined his touch on the mound, learned he was tipping his pitches—and how to fix that—and discovered his best chance to play in the major leagues rested in his future as a pitcher.

All during one school year. “I can’t say enough about Elon, because they were so good to me up there,” says Brewer in a slow, Southern drawl from his home in Cheraw, S.C., the town where he was born, raised and has lived for most of his life.

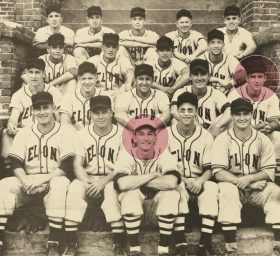

The name “Tom Brewer” is nowhere to be found among the list of letter winners in the history of Elon baseball. But Brewer’s experience at Elon isn’t a figment of his imagination. There is an Austin Brewer—Tom Brewer’s middle name—listed as the team’s strikeout leader in 1951. That’s a mark made possible by Brewer’s relationship with scout Mace Brown. It was Brown’s friendship with Elon coach Jim Mallory that forged a connection and led to a workout for Brewer. With no prior knowledge of Elon, Brewer was invited to visit, traveled to the school for a workout and accepted an offer to join the team, all in a week’s time. “I worked out for them up there, and that was it. [Mallory] said, ‘You wanna come to Elon? You’d fit right in here.’ I said, ‘That’d be fine,’” Brewer recalls.

And the rest, as the saying goes, is history.

Brewer came to Elon as more of an infielder than a pitcher, with the ability to play third base or shortstop. The team already had several players at those positions, among them Elon Sports Hall of Famer Scott Quakenbush ’53, who Brewer noted would have been hard to move out. When Mallory, whose own professional career lasted for 54 games, asked him whether he’d rather be an infielder or a pitcher, he asked Mallory in return what his opinion was. “He said, ‘The quickest way for you to get to the major leagues is with your arm,’” Brewer says. “I said, ‘OK, we’ll go whatever way you say.’”

It was a humbling experience not too uncommon in the sport. “You know when you go out and a ballclub just hits you hard … sometimes it will stick in your mind. ‘How in the world do they keep doing that to you?’” Brewer says. “After you do it and get hit a few times, you wonder why they’re hitting you so hard; you change in a hurry.”

Brewer also added to his pitch arsenal while at Elon. Arriving as a fastball-curveball pitcher, he wanted to add dynamics to what pitches he could call upon, so a changeup was added. Brewer’s work ethic also led him to learn different types of fastballs. He already had a sinking fastball, but he started to work on a cutter: a pitch that later led his Boston Red Sox teammate Ted Williams, one of baseball’s greatest hitters, to claim that Brewer broke too many of his bats during spring training. Elon went 16-9 in Brewer’s one season, winning nine of the last 10 games. But in April of that spring, Brewer signed a professional contract with Boston.

After finishing the season with the Hi-Toms, Brewer was drafted in December of 1951 and served in the Army for two years. He was never deployed, although there were a couple of times he thought he would be called upon during the Korean War. His pitching arm stayed sharp, playing in active service leagues that featured major leaguers scattered throughout the country. He had a 35-7 record in those two seasons. Though by then married, Brewer planned on returning to Elon when he was discharged in December of 1953. Then came a spring training invitation from the Red Sox. “I said, ‘If I make the team, I’ll probably just stay in baseball.’ And that’s what happened,” Brewer says.

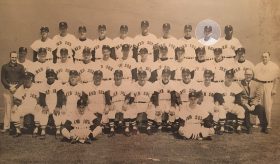

The then-22-year-old threw 27 straight scoreless innings in his first professional spring training, earning a spot with the Red Sox as a reliever. That didn’t last long either; he was moved into the rotation in his rookie season. Brewer had cracked his way into a major league rotation, pitching home games in Fenway Park and accelerating a baseball education that had taken shape at Elon. There was an art to each part of baseball for Brewer, and he saw the best way to learn that of pitching was to listen to Williams, an eventual Hall of Famer who won six batting titles, two of which came in 1957-58, when Brewer was on the team.

“Ted and I were good friends, when we traveled on the planes, he and I would sit together,” Brewer says. “I told him, ‘I want to learn all I can about pitching, but the only way I can learn about pitching is to listen to you talk about hitting.’ Every time he got a new kid on the block, they wanted to talk about hitting. I would eavesdrop, I wouldn’t even tell him I was around, I would just get up that close to him to hear what they were talking about.”

“Ted and I were good friends, when we traveled on the planes, he and I would sit together,” Brewer says. “I told him, ‘I want to learn all I can about pitching, but the only way I can learn about pitching is to listen to you talk about hitting.’ Every time he got a new kid on the block, they wanted to talk about hitting. I would eavesdrop, I wouldn’t even tell him I was around, I would just get up that close to him to hear what they were talking about.”

They were friends, with a respect derived from some of the stubbornness and desire to improve that was on display at Elon. During spring training, Williams asked pitchers to throw the ball down the middle in batting practice. Brewer refused, telling Williams, “I’m not going to throw you something fat down the middle of the plate to hit every time I come out here to pitch batting practice. I’m going to work on things that I need to, to help me.”

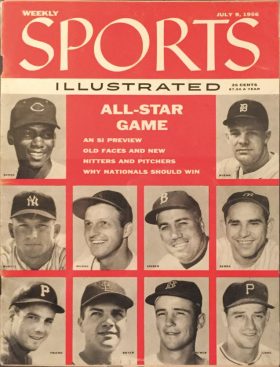

Brewer was 91-82 in eight seasons with the Red Sox, his best season coming in 1956. That’s when Brewer was 19-9 with a 3.50 earned run average and a selection to the American League All-Star team (he even made the cover of Sports Illustrated). He led Boston in wins, complete games (15), shutouts (four) and innings pitched (244 1/3), and also racked up 28 hits over 94 at-bats (a .298 average). “He had a stellar career,” says John Britt, who has written about Brewer. “He had a winning record in a losing team. He pitched against everybody—Mickey Mantle, Roger Maris, Yogi Berra. He was good.”

In his last season in 1961, during which he turned 30, Brewer was limited to nine starts—he had at least 28 in each of the previous six seasons—by arm fatigue. He decided he could no longer help the Red Sox. “It was just a matter of me being a little bit more relaxed and saying, ‘No, you can’t do all this that you want to do.’ I wanted to do what was right to help the ballclub and play my part as a ballplayer, and to help anybody I could to progress as much as they possibly could,” he says.

More than any other work, Brewer says he got the most satisfaction out of working with young pitchers. He took pride in weeding bad habits out of players 10, 12 years of age—habits like the ones he lost at Elon. “They all wanted to learn, and it was a good feeling to work with kids of that age,” he says. “Before we started, I would have a conversation with all the kids and tell them what I expected. … A lot of them went on to pitch in high school. That was a good feeling, knowing that they were taught the right way to start with.”