The story of the black experience at Elon includes highs, lows and amazing perseverance by determined individuals.

The Elon that Glenda Phillips Hightower and Eugene Perry ’69 remember is not the same one they encountered when they visited the campus in February. Some of the buildings looked the same and many of the oaks they had passed on their way to class were still there. Yet it all felt completely different.

As the first black students to attend Elon full-time, their experience was shaped by societal norms that had kept blacks and whites separated throughout their entire lives. And while there was no violence during their time as students, their experience was very different from that of today’s black students. “[Times] were different,” Hightower says. “They were just different. Race relations had to make some giant leaps to get where we are now.”

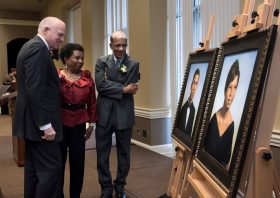

Hightower and Perry couldn’t have imagined in the 1960s, that more than 50 years later, they would be standing in Moseley Center, surrounded by a large crowd of students, faculty, staff and administrators who had come together for one purpose: to unveil their portraits in recognition of their pioneering spirit.

“They did something extraordinary, something historic, and something that we perceive today as incredibly generous,” said Elon University President Leo M. Lambert during the unveiling. “They persevered. And in the process, Glenda and Eugene changed Elon College and paved the way for thousands of black students, faculty and staff to follow them. Thank you for never giving up. Thank you for leading this institution to a better place. Thank you for choosing the path of love and sacrifice.”

It was a path they took not knowing where it was going to lead, a path that in some ways had been forged by others even before Hightower and Perry were admitted at Elon, and one that the institution and black students continue to broaden for generations to come.

Deep roots

Even before the college was founded in 1889, a strong black community had settled near the railroad tracks at what was called Mill Point, near the current intersection of Williamson and Lebanon avenues. In “From a Grove of Oaks: The Story of Elon University,” George Troxler, professor emeritus of history and university historian, writes that having labor available for loading and unloading railway cars likely influenced area mill owners to ensure a railway stop was established in that location.

Regardless of what first attracted them to that area, the presence of a black Lutheran church at Mill Point makes it clear this was a grounded community. The church appears in records as far back as 1877, making it the first black Lutheran congregation to be recorded in North Carolina. Blacks had few opportunities back then, having lost the short-lived liberties they enjoyed during Reconstruction, the period from 1865 to 1877 following the Civil War. In the aftermath of an attempt by white and black Populists and Republicans to gain control of state governments, rigid anti-black laws were enacted in Southern states at the end of the 19th century. These laws, which came to be known as “Jim Crow laws,” made it almost impossible for blacks to vote, prohibited them from holding local offices and mandated racial segregation in all public facilities, including schools. With no political or economic power, blacks were once again suppressed and restricted by laws that determined where they could live, work and go to school. “This was three steps backwards in terms of race relations,” Troxler says. “There were a lot of racial tensions. It would take time for mindsets to change.”

It was against this backdrop that Elon opened its doors. Not surprisingly, black men and women from the nearby community, now known as the Ballpark Community, participated in the early growth of the college, starting a relationship with the institution that continues to this day. At first, blacks served as hired hands, doing mostly housekeeping work for faculty and students. In “Elon College: Its History and Traditions,” Durward T. Stokes gives the account of Pink B. Comer, a black man who was hired in the early 1900s to care for the Rev. James W. Wellons, an original member of the college board of trustees, when he lived at the college after retirement. Comer also looked after the athletic grounds. “There were few opportunities for people in this community to work except as domestics, custodians and in agriculture,” Troxler says, adding that textile mills were strictly segregated and there was no nearby opportunity for them to be tenant farmers. The college offered a steady source of employment.

Indeed, some, such as Comer and maintenance worker Andrew Morgan, worked for the college for decades, becoming fixtures in the community. When the school laid out a new athletic field south of the campus, in what is now The Station at Mill Point, it named it Comer Field. When Morgan’s house burned down in the 1950s, the college raised funds to pay for it to be rebuilt. And when he died in an accident a decade later, then President J. Earl Danieley ’46 gave the eulogy at his funeral. Morgan’s wife, Hattie Burton Morgan, cooked in the dining hall and several other members of their extended family have worked at Elon in various capacities throughout the years.

Janice Ratliff, a program assistant in the Office of Student Health and Wellness, who is retiring in May after 30 years of service, is one of them. Morgan was her great uncle, though she considers him her grandfather since he raised her mother. Like him and many other relatives who also found employment at Elon, Ratliff grew up in the Ballpark Community. “They all moved to the area after [Morgan] got the job at Elon,” she says. “Of the original family members who didn’t move away, about 80 percent of them worked at Elon and the descendants are still here,” she says. “There is at least a third generation of one family still working here.” Growing up in a segregated community, Ratliff never thought she would one day work at Elon, at least not as a staff member. “When I graduated from high school [in 1961], Elon wasn’t even an option,” she says. “Black people didn’t work here except for in housekeeping and dining services. Things have evolved.”

The road to integration

While the Christian Church, Elon’s founding denomination, was mostly a rural, white, Southern church that often aligned with the social order of the time, there are clues in the university’s archives that provide an insight into the institution’s desire to be more inclusive. Leonidas L. Polk, a farmer and the leader of the Farmers’ Alliance, a movement that received much support from black voters during the 1890s, was invited to speak at the school’s Cornerstone Laying Ceremony in 1889. Though illness prevented Polk from attending, “there must have been some political consideration from the board to make that choice,” Troxler says.

In 1927 Elon hosted a convention of the Student Volunteer Movement for Foreign Missions. Twenty North Carolina schools, including six black institutions, sent representatives. According to news reports at the time, it was the first time black students had been invited to a conference in a Southern white college. The event was described by Elon President W.A. Harper in his book, “Character Building in Colleges,” as an example of how a “vexing and ever recurring Christian problem” was addressed in a Christian way. “Here was a real situation loaded with dynamite, or prophetic with hope for a Christian solution of the [race] question,” Harper wrote, adding that the campus “became a laboratory in the race question for about a month,” with classes, discussion groups, student meetings and chapel services engaging in discussions. “What Harper and the college were doing was liberal for the day,” Troxler says. “This speaks, in some respects, to the fact that we have been a leader. This was the first Student Volunteers meeting in the South where black and white students were together.” Yet, Troxler adds, at other times, “we haven’t been enough of a leader.”

That was the conclusion L’Tanya Richmond ’87 reached when she decided to tell the story of Elon’s first black students as she created a “Wall of Fame” in Elon’s Multicultural Center, and later as she prepared her master’s thesis in 2005. Prior to the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education, in which the U.S. Supreme Court declared state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students to be unconstitutional, white and black schools in Alamance County were significantly unequal in terms of facilities, faculty and library resources. As Richmond details in her thesis, no action was taken to integrate public schools in the area for almost 10 years. While state colleges and universities adopted the court’s ruling starting in 1956, it wasn’t until 1963, the year before the Civil Rights Acts was passed, that Elon and other Southern private colleges started a slow integration process.

Elon chose to open its doors to black students at the same time other schools were integrating. Guilford College and Wake University enrolled their first black students in 1962. Duke University admitted black undergraduate students in 1963, while Davidson College did so the following year. “We were not the first nor the last,” Troxler says. It was a step in the right direction, though it was limited for various reasons. While there was support from the national United Church of Christ to integrate, the local church might have felt differently, Troxler says. In fact, the decision to integrate was made by President Danieley alone and was not part of a comprehensive plan for desegregation. Danieley says he knew that if he asked the board of trustees to pass a resolution in favor of integration, as the national church had asked him to do, they could have voted against it, closing the door for any chance at integration. Instead, the administration decided to reach out to the local schools looking for black students in good academic standing who were good scholarship candidates. “When we get an application,” Danieley recalls telling church officials, “we are going to accept this student.”

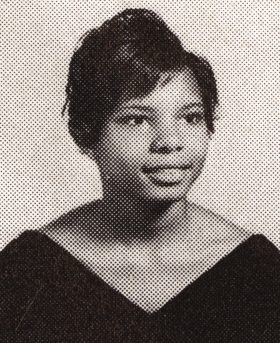

When Hightower, an honors student at a local high school, applied, she was immediately accepted. The oldest of nine siblings, she had been taught by her parents about the power of education. But nothing had prepared her for an integrated classroom. She had attended black schools, lived in a black community and worshipped in a black church her entire life. While Elon wasn’t her first choice, it was the closest to her family and the one that offered the most financial assistance. “I was not financially prepared to attend college,” she told Richmond in a 2005 interview. “Naturally, the schools to which I had applied were black institutions that had very little funding for scholarships. … Elon offering admission and tuition, that was the answer.”

She arrived at Elon in fall 1963 as a pre-medicine major and joined the marching band as a clarinetist. Her scholarship only covered the cost of tuition, so she continued living at home. She walked unescorted to class each morning, and while she didn’t experience open hostility on campus, there was little interaction with her peers. Just as segregation laws had shaped her life, her white peers had been conditioned to see black students differently. At the same time, she didn’t know how to behave around black employees at the school. “We were not clear, or not comfortable, that we should talk to each other,” she recalls. “Race relations in the 1940s, ’50s, ’60s were rigid, severe, unaccepting, uninviting and unwilling. So to be here, neither of us wanted the other to be in trouble.” In the classroom, the challenges continued. While Hightower was valedictorian in high school, she soon realized she had not received adequate preparation. The textbooks she had often used in class were old or inferior in quality to those used by her white counterparts.

She withdrew from Elon in 1964, due in part to an illness. Though she eventually earned a degree from the University of Iowa in 1974 and spent her entire career working as a nurse, her decision to leave Elon weighed heavily on her mind for many years. She felt as if she had let her community down. Richmond describes her withdrawal as “inevitable.” With no support system in place, it was a tall order for her to succeed. “Administrators and faculty at Elon were white and had also grown up with Jim Crow laws. They had experienced little to no interaction with blacks,” Richmond writes. “The focus of most Southern private colleges and universities at this time was to secure federal funding and do what was required legally, not morally.”

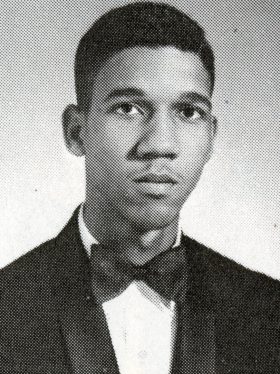

Perry came to campus in fall 1965 determined to see his Elon experience through to the end. Just like with Hightower, Elon wasn’t his first choice, but it was the most economical option. He also joined the marching band. Danieley was always encouraging him and professors were cordial to him, he told Richmond in an interview, but he did experience a few racially charged incidents around campus, though he never reported them. “I didn’t discuss it because I think it was just the way things were,” he told Richmond. Instead, he preferred to focus on his studies—he majored in social science—and in 1969, he became the first black student to earn an Elon degree. He went on to receive two master’s degrees and had a varied career that included serving as a Navy chaplain, a teacher and a drug counselor.

From the 1960s onward

In the following years, many more black students followed in their footsteps, their experiences varying depending on their expectations and backgrounds. The Rev. Marvin Morgan ’71 describes his student experience as “overwhelmingly positive,” adding that his Elon education transformed his life. Prior to enrolling at Elon in January 1968, Morgan had spent the previous two and a half years with IBM, in Rochester, Minn., and later at the Research Triangle Park in North Carolina. “That job was offered to me prior to my completion of my senior year at James E. Shepard High School in Wake County, where I was an honor student,” he says.

Race relations were still difficult nationwide and riots were common, particularly after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in April of 1968. All this uncertainty, Morgan says, gave new meaning to a phrase in the Negro National Anthem, “when hope unborn had died.” “That’s what it felt like outside the campus,” he says, adding that the campus for him “was an incubator for improved racial relations: if we study together and then later live and work together, that could make a difference.” He fondly remembers the vast outpouring of support he and other minority students received following King’s assassination.

That show of support and empathy by fellow students and faculty, he says, helped to shape his decision to remain in school at a time when some black students dropped out of predominantly white institutions in order to reassess the full implications of gaining an education in such a setting. Like Perry, he was determined to stay at Elon. “I felt torn for having made that decision, but grateful,” he says. “I felt the need to be out in the streets, where the ‘real action’ was taking place. I later learned there was real action taking place as we grew in our levels of tolerance at Elon.” He went on to earn a master’s degree from Duke University Divinity School and a doctoral degree from Drew University.

That show of support and empathy by fellow students and faculty, he says, helped to shape his decision to remain in school at a time when some black students dropped out of predominantly white institutions in order to reassess the full implications of gaining an education in such a setting. Like Perry, he was determined to stay at Elon. “I felt torn for having made that decision, but grateful,” he says. “I felt the need to be out in the streets, where the ‘real action’ was taking place. I later learned there was real action taking place as we grew in our levels of tolerance at Elon.” He went on to earn a master’s degree from Duke University Divinity School and a doctoral degree from Drew University.

As more black students enrolled at Elon during the 1970s, they gained enough numbers and confidence to form their own support systems. In 1974 the Black Cultural Society was established, serving as the catalyst for other groups to form. A singing group led by members of the physical plant soon became the Elon College Gospel Choir, which was formally established in 1977, enriching the spiritual experience of students. The following decade, chapters of four historically black Greek organizations were established, providing much-needed opportunities for social interactions. Bryant Colson ’80 entered Elon in fall 1976. He served as the editor of The Pendulum for the 1978-79 academic year and was elected president of the Student Government Association his senior year. His leadership legacy, Richmond wrote, continued at Elon at a time when black student enrollment was gradually increasing.

Even as students started gaining ground, they relied heavily on black staff members for support, including Ratliff. When she came to Elon in 1980 to work in the Office of Cooperative Education, she joined a core group of black office workers, including Marsha Boone in admissions and later Betty Covington in academic advising, who had been hired in an effort to diversify the make-up of the staff. This gave Ratliff the opportunity to be a much-needed source of encouragement for a new generation of diverse students. “Black students would come to our office for support because they didn’t have any other place to go,” Ratliff says. “They came to Elon because of scholarships or other financial aid. There was a need for somebody to support them.”

Along the way, these staff members impacted the lives of countless black students, such as Darryl Smith ’86, who came to Elon in the 1980s on an athletic scholarship and worked in the cafeteria washing dishes to earn some income. “They believed in me and supported me,” he says of Elon’s black staff members, as well as others, like Lela Faye Rich in advising, who impacted his time as a student. While the black student community was small, Smith says, it was a tight community. “We supported each other and took care of each other,” he says. “We couldn’t imagine just how a simple gesture, like a home-cooked meal when we were away from home, or just words of encouragement can shape someone’s life. They were proud to see the progress we had made that they might have not made, and behind the scenes, some of them lived through us.”

While much had changed at Elon, certain instances of prejudice remained. When Mary Carroll ’81 entered Elon in 1977, she was the only black student in her dormitory (Staley Hall). While she had corresponded with her roommate over the summer, when the roommate and her mother saw her on Move-in Day, they were visibly shocked, she told Richmond in a 2004 interview. “I truly believe to this day that she thought I was white,” Carroll continued in that interview. “They never said, ‘I don’t want her sharing the room with a black girl,’ but it was very obvious.” She didn’t see the girl again.

While much had changed at Elon, certain instances of prejudice remained. When Mary Carroll ’81 entered Elon in 1977, she was the only black student in her dormitory (Staley Hall). While she had corresponded with her roommate over the summer, when the roommate and her mother saw her on Move-in Day, they were visibly shocked, she told Richmond in a 2004 interview. “I truly believe to this day that she thought I was white,” Carroll continued in that interview. “They never said, ‘I don’t want her sharing the room with a black girl,’ but it was very obvious.” She didn’t see the girl again.

Two years later, when Carroll, who was representing the Black Cultural Society, was elected Homecoming Queen in 1979, she became the first black student to be crowned queen. That was also the first Homecoming Court not to be included in the school yearbook. “The black student community was so angry and shocked by the yearbook staff’s negligence that they decided to organize a protest on campus to burn their yearbooks,” Richmond writes. “Black students were upset with Elon’s administration because the omission had been acknowledged as a simple oversight. … It shows how the students in numbers start to feel empowered to challenge uncharted areas of social and governmental participation.”

Decades later, Elon changed its housing policy to make it clear it embraced diversity, respect and responsibility and that the institution was committed to offering an “integrated learning community for our students to grow and become active members of a global society,” Richmond wrote. However, it wasn’t until 1987 that Elon hired Wilhelmina Boyd in the Department of English, who went on to become Elon’s first black tenured faculty member. A beloved teacher, she developed new African-American courses that eventually gave way to the founding of the African and African-American studies program in 1994. A student award was established in her honor in 2008, and in 2012 the home of the interdisciplinary program in Alamance Building was named the Wilhelmina Boyd Suite.

Additional support for recruiting and retaining minority students was implemented during the late 1980s and 1990s. In 1988 Richmond became the first black admissions counselor whose main purpose was to develop a recruitment plan to increase minority enrollment, something she did successfully. In 1992 the African-American Resource Room was established after a group of black students petitioned the school to set aside a space on campus where all faculty, staff and students could explore cultural diversity, with an emphasis on African-American culture. The following year, the Office of Minority Affairs was created and Richmond was appointed as its founding director. The Multicultural Center opened a decade later under Richmond’s leadership to better serve an increasingly diverse student body and support diversity education opportunities for all students, and in 1997 she created Elon’s “Wall of Fame.” Richmond also established Elon’s Black Excellence Awards Banquet, which recognizes black students for their academic achievement. The banquet was renamed the Phillips-Perry Black Excellence Awards Banquet in 2006 to honor two of Elon’s first black students.

Additional support for recruiting and retaining minority students was implemented during the late 1980s and 1990s. In 1988 Richmond became the first black admissions counselor whose main purpose was to develop a recruitment plan to increase minority enrollment, something she did successfully. In 1992 the African-American Resource Room was established after a group of black students petitioned the school to set aside a space on campus where all faculty, staff and students could explore cultural diversity, with an emphasis on African-American culture. The following year, the Office of Minority Affairs was created and Richmond was appointed as its founding director. The Multicultural Center opened a decade later under Richmond’s leadership to better serve an increasingly diverse student body and support diversity education opportunities for all students, and in 1997 she created Elon’s “Wall of Fame.” Richmond also established Elon’s Black Excellence Awards Banquet, which recognizes black students for their academic achievement. The banquet was renamed the Phillips-Perry Black Excellence Awards Banquet in 2006 to honor two of Elon’s first black students.

Many black students who enrolled at Elon from the 1990s forward “felt totally inclusive in the college environment,” Richmond wrote. The college had changed and the experiences of black students before they came to Elon had also changed. That was certainly the case with Marvin Morgan’s children, Akilah and Marvin Jr., who graduated from Elon in 1996 and 2009, respectively. He can still remember walking across campus with his oldest daughter in 1994 while reminiscing about his days at Elon. “My daughter said, ‘Dad, this is not the same Elon you attended.’ She was absolutely right,” he says. “Virtually everything had changed in those 20 years. At a very early point in life, people are having more diverse cultural experiences and that has helped to shape their response to all stimuli. My children spent their entire lives in predominantly white schools. When they arrived at Elon, I thought they were going to find their way to the Multicultural Center, make their presence known and get involved in issues.”

When he stopped by the center during one of his visits to campus, Morgan discovered that neither of his children had visited the space, nor did the staff know them. “There was a reason for that,” he says. “My children’s background had been very different from my own and that helped to shape their way of functioning around Elon.”

The road ahead

As the campus continued to diversify, the 21st century brought different challenges and opportunities for the university to improve the experience of all students. In 2010 Lambert began the implementation of the Elon Commitment, a strategic plan to guide the institution for the next 10 years. Among its top priorities is an “unprecedented commitment to diversity and global engagement.” In terms of racial diversity, that meant the adoption of diversity plans by offices across campus and the implementation of new programs for students. Faculty members are also encouraged to create and incorporate diversity infusion projects in the classroom and campus conversations on race and diversity are common.

Randy Williams was hired as presidential fellow, special assistant to the president and dean of Multicultural Affairs, and in fall 2014 the Multicultural Center’s name was changed to The Center for Race, Ethnicity, & Diversity Education to more accurately reflect its role in the university’s diversity and inclusion efforts. “Most societal institutions, including higher education, are grappling with creating a more inclusive environment for their communities,” says Williams, who was recently appointed associate vice president for campus engagement. “Having been in higher education for more than 20 years, I am proud to be a member of the Elon community, which works toward the vision of everyone experiencing inclusion, despite the challenges of reaching such a goal.”

For Morgan, who serves on the board of trustees, the diversity portion of the Elon Commitment speaks volumes regarding how far Elon has come over the years. “If we deal creatively with issues related to diversity here at Elon, our graduates will be enabled to deal with these and other issues when they travel, study and work abroad,” he says, adding he is particularly thrilled to see the diversity that is now evident among Elon faculty and staff. Faculty ethnic diversity has increased in recent years from 10 percent to 15 percent, and from 18 percent to 22 percent for staff. It’s a reality that hasn’t escaped Associate Professor of English Prudence Layne. A past coordinator of the African and African-American studies program, she has been promoting and advocating for racial diversity on campus since joining the Elon faculty in 2005. “We’ve come a mighty long way in many regards,” Layne says, adding that blacks are now represented on the board of trustees and senior positions, as well as in leadership positions across campus. “We’ve had a lot of firsts, but we still have a lot of other firsts to get to, a lot of barriers to dismantle.”

For Morgan, who serves on the board of trustees, the diversity portion of the Elon Commitment speaks volumes regarding how far Elon has come over the years. “If we deal creatively with issues related to diversity here at Elon, our graduates will be enabled to deal with these and other issues when they travel, study and work abroad,” he says, adding he is particularly thrilled to see the diversity that is now evident among Elon faculty and staff. Faculty ethnic diversity has increased in recent years from 10 percent to 15 percent, and from 18 percent to 22 percent for staff. It’s a reality that hasn’t escaped Associate Professor of English Prudence Layne. A past coordinator of the African and African-American studies program, she has been promoting and advocating for racial diversity on campus since joining the Elon faculty in 2005. “We’ve come a mighty long way in many regards,” Layne says, adding that blacks are now represented on the board of trustees and senior positions, as well as in leadership positions across campus. “We’ve had a lot of firsts, but we still have a lot of other firsts to get to, a lot of barriers to dismantle.”

A report last fall from the university’s Presidential Task Force on Black Student, Faculty, and Staff Experiences showed just how much work is still left to do. Among other things, the report found that almost 60 percent of black students surveyed felt Elon needed to make improvements to be considered an inclusive campus. Among 63 black faculty and staff who participated in the survey, 74 percent said they have experienced disparaging race-related comments at Elon. Of the 151 black students who also took the survey, 65 percent reported the same. “Whether the subject is race or understanding the religious and spiritual traditions of others, we have to be invested for the long term,” Lambert says. “We strive to be an institution of higher learning that is always getting better on every front, including being an ever more inclusive community.”

Elon’s continuing work certainly feels the influence of national racial tensions. The August 2014 shooting death of Michael Brown, a black teenager, at the hands of a white police officer in Ferguson, Mo., sparked weeks of protest nationwide and drew attention to the Black Lives Matter movement, which has been described as a new civil rights campaign for the modern era. At Elon, racial incidents, including acts of racial bias, were reported in 2011, 2013 and 2015, sparking campus-wide outcry and conversations that, while painful at times, Layne says, have been healthy. “Our community, including non-university residents, has shifted to think in ways and about issues that were not covered before,” she says. “Issues of race, identity and culture are being discussed throughout the institution.”

“We are committed to thinking carefully about how our corner of the world can make an important contribution to systemic change that is so much in need across our nation,” Lambert says. “They are many powerful voices in our nation today calling for us not to show our highest character as an American people. Closer to home, we have witnessed members of our own community who have been targets of slurs for one reason only—because they are black. We cannot afford to have any group feel at the margins of campus life or to waste precious intellectual and emotional energy on questions about whether Elon is a place where they can belong and thrive.”

For that to happen, deeper questions need to be considered. The issue of class disparity due to race, for instance, hasn’t been solved, Layne says. “We sometimes have generations of families working in the Physical Plant, for example, but why haven’t they broken the cycle to move beyond those positions? Have we talked about that?” she asks. “They clean and maintain the physical environment of our institution, walk the annals of history in the library but don’t have access to the same educational resources.” Racism and oppression operate in systematic, pervasive ways, she adds, and are rooted in a “fundamental ignorance and lack of understanding of human beings and who we are.”

For that to happen, deeper questions need to be considered. The issue of class disparity due to race, for instance, hasn’t been solved, Layne says. “We sometimes have generations of families working in the Physical Plant, for example, but why haven’t they broken the cycle to move beyond those positions? Have we talked about that?” she asks. “They clean and maintain the physical environment of our institution, walk the annals of history in the library but don’t have access to the same educational resources.” Racism and oppression operate in systematic, pervasive ways, she adds, and are rooted in a “fundamental ignorance and lack of understanding of human beings and who we are.”

Black Student Union President Alex Bohannon ’16 agrees. “We don’t have people walking around in white hoods as much as they used to, but because of that change, it’s confused some folks into thinking that racism no longer exists or that we can worry about it less,” he says. While he doesn’t believe Elon has an “abundance of racists,” Bohannon says there is a culture of apathy on campus that will take time to change because it involves diversifying the student body. That can only happen by providing additional financial aid to be able to attract and support students from all types of backgrounds. “As human beings, we are conditioned to be concerned with our own circles, with our own self,” he says. But “when you have different people from different marginalized identities in a place, it adds a sense of empathy around everyone else’s struggle because everyone is aware that everybody has their own struggle.”

Despite all these challenges, Bohannon would not change his Elon experience for anything. “I have been challenged a huge amount and not just in terms of academics and intellect but personally my identity has been challenged,” he says. “I am more salient in all of the different forms of my identity because I came to Elon. And it is the challenges, the difficulties that make us better and have a more profound change.”

It’s a perspective both Hightower and Perry also share. Having their portraits unveiled brought their Elon experience full circle, for it acknowledged their personal struggles as part of the larger context of how the black experience continues to evolve at Elon. “When I talk to some of my brothers or former classmates, my experience at Elon was different from what they experienced,” Perry says. “But I hold no regrets for the Elon experience because, in the words of Robert Frost, I guess it put me on that road not chosen, and I still feel like I’m sometimes on that road.”

It’s a perspective both Hightower and Perry also share. Having their portraits unveiled brought their Elon experience full circle, for it acknowledged their personal struggles as part of the larger context of how the black experience continues to evolve at Elon. “When I talk to some of my brothers or former classmates, my experience at Elon was different from what they experienced,” Perry says. “But I hold no regrets for the Elon experience because, in the words of Robert Frost, I guess it put me on that road not chosen, and I still feel like I’m sometimes on that road.”

For Hightower, her portrait is a reminder that despite all the challenges she endured, Elon chose to integrate the campus in a peaceful manner, and for that, she’s grateful. “When I was coming to this institution by myself, I thought about other places that were violent,” she says. “Other places that weren’t handling it the way that we were handling it.” To those who see her portrait in Moseley Center, she adds, “it’s going to say, come one, come all. See what can happen to you? Give it an opportunity.” Moving forward, she hopes the black student experience at Elon is not seen as a separate experience but rather as “part of the community of Elon—an integrated community that says that every single person invited to matriculate at this university is valuable to us. Every person. That’s what I would like to see.”

Adam Constantine ’10 contributed to this story.