More than 60 years since the armistice was signed, the threat of nuclear war still looms between the U.S. and North Korea.

By Roselee Papandrea Taylor

By Roselee Papandrea Taylor

C.K. Siler ’54 didn’t often think about the time he spent in the Army fighting in the Korean War. Recurring pains in his legs and feet—remnants of the frostbite he endured while trekking up the frigid mountains of North Korea—were his most consistent reminder of the war he left behind 64 years ago. The Siler City, North Carolina, native moved on quickly when he returned home from the front lines, finishing his final year at Elon with a determination he hadn’t known until he experienced combat in a war zone. “I guess it did change me some,” says Siler, now 87 and living in Greensboro. “It changed the way I looked at things. I worked a whole lot harder in school to graduate than I had before.”

As for the two countries locked in battle from 1950 to 1953, little has changed between the U.S. and North Korea. While military forces are no longer engaged in hand-to-hand combat in Korea and it’s been more than 70 years since atomic bombs were used in Japan, the threat of nuclear war looms overhead as if the armistice, signed in July 1953 to end the fighting, was just yesterday. “There is a sense of real urgency and crisis about it now,” says Jason Kirk, an associate professor of political science and policy studies who focuses part of his scholarship on American foreign policy, nuclear issues and nuclear deterrence. “It’s not as if this issue is out of nowhere. It goes back to the Clinton, Bush and Obama administrations. President Obama told President Trump that he thought this would be the No. 1 foreign policy issue confronting the Trump administration.”

The Korean War, an Asian war fought in the shadow of Hiroshima and Nagasaki with developing Soviet nuclear capability as a backdrop, set the stage for how wars would be fought from that point on—limited, but often inconclusive as well. “In the North Korean consciousness, the Korean War might as well have been last week and not something that happened in the middle of last century,” Kirk says. “It is so real and visceral for them, not least because the regime feeds continual reminders to bolster its legitimacy.”

The fight over North Korea’s arsenal of nuclear weapons, which imminently may include intercontinental ballistic missiles powerful enough to reach the mainland U.S., is a constant in the news today. It’s a reality that makes it impossible for Siler not to consider what might have happened if the Korean War had a more definitive end. As for Siler, he was injured twice and received two Purple Hearts. He also lost his only shot to play baseball in the major leagues. He spent his 36-year career coaching football and baseball as well as men’s and women’s basketball. During his 26 years as a head coach in Guilford County, North Carolina, he won 12 conference championships. He is a member of the Elon Sports Hall of Fame for both football and baseball and the football field at Southern Guilford High School was named after him. “I had a pretty good career, and I loved it,” Siler says. “I never woke up in the morning dreading going to school.”

The fight over North Korea’s arsenal of nuclear weapons, which imminently may include intercontinental ballistic missiles powerful enough to reach the mainland U.S., is a constant in the news today. It’s a reality that makes it impossible for Siler not to consider what might have happened if the Korean War had a more definitive end. As for Siler, he was injured twice and received two Purple Hearts. He also lost his only shot to play baseball in the major leagues. He spent his 36-year career coaching football and baseball as well as men’s and women’s basketball. During his 26 years as a head coach in Guilford County, North Carolina, he won 12 conference championships. He is a member of the Elon Sports Hall of Fame for both football and baseball and the football field at Southern Guilford High School was named after him. “I had a pretty good career, and I loved it,” Siler says. “I never woke up in the morning dreading going to school.”

Still, as a result of the draft, Siler had to give up a contract to pitch for the Boston Red Sox. And while the armistice put an end to the fighting, a two-mile-wide demilitarized zone still divides North and South Korea to this day. It was a limited war—a war without a winner—an outcome an avid sports fan can’t help but wonder about. “There is no doubt in my mind that we could have taken the whole country,” Siler says. “What’s going on now wouldn’t be happening. If [Gen. Douglas] MacArthur would have been left alone, there wouldn’t be a North and South Korea now.”

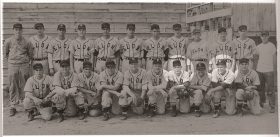

Siler first arrived at Elon College in 1947, a recipient of a football scholarship that was his ticket to an education. Without it, he says, college would have been out of the question. Sports, football and eventually baseball, were his lifeblood. During his sophomore year, James Mallory, a former outfielder for the Washington Senators, St. Louis Cardinals and New York Giants, started a four-year stint at Elon as head football and baseball coach. When baseball season rolled around in the spring, Siler asked Mallory if he could join the team. “He asked what I did,” Siler recalls. “I told him I was catcher. I was a catcher for about five days when he told me I was no longer a catcher.”

Mallory wanted to take advantage of Siler’s throwing arm and made him a relief pitcher. Not long after, Siler was pitching games regularly. The switch from catcher to pitcher was fortuitous but news that he was drafted for military service, received near the end of fall semester his junior year, changed the course of Siler’s career. He was expecting to be drafted, as most of his peers were at the time. By December 1950, American troops had already been in Korea for five months. Siler was sent to Fort Jackson, South Carolina, for basic training. When he finished, he celebrated by marrying his late wife, Billie Burgess, who he met through a friend while he was at Elon. They had been married 64 years when she died in 2015.

Siler was sent to leadership school after that and by the summer of 1951, he still hadn’t been sent overseas so he pitched for a minor league team in Sanford, North Carolina. They sold his contract to the Boston Red Sox. He would have reported to the team the following spring. Instead, he left for Korea that September. “That ended that,” Siler says. “I played some semi-pro baseball after the war, but I never figured I had a chance to do too much. It would have been great. I would have enjoyed it if I had the chance, but things have turned out pretty well.”

Siler was sent to leadership school after that and by the summer of 1951, he still hadn’t been sent overseas so he pitched for a minor league team in Sanford, North Carolina. They sold his contract to the Boston Red Sox. He would have reported to the team the following spring. Instead, he left for Korea that September. “That ended that,” Siler says. “I played some semi-pro baseball after the war, but I never figured I had a chance to do too much. It would have been great. I would have enjoyed it if I had the chance, but things have turned out pretty well.”

Siler, who was assigned to the 3rd Infantry Division, 1st Battalion, was promoted from private to corporal as soon as he got to Korea. “I was in a combat unit as a foot soldier,” he says. “As soon as I got there, most of my time from then on was in a combat zone. Contrary to what people think, my outfit was primarily opposed by Chinese soldiers. We hardly ever saw any opposition from North Koreans.”

China’s relationship with North Korea was a factor for the U.S. then as now. The two countries have been allies for a long time. China is North Korea’s most important trading partner and main source for food and energy. The collapse of the North Korean government, would be a “nightmare scenario as far as China is concerned,” Kirk says. “China would be flooded with North Korean refugees, which would be politically and economically destabilizing.”

There is no doubt that Chinese intervention in the Korean War changed the nature of the war and its potential impact on the U.S. “MacArthur said from the field, ‘We face an entirely new war,’” Kirk says. “When the Chinese intervened, it made it much harder on the United Nations forces under U.S. command.”

When the Korean War started, America viewed it as a border dispute between two unstable dictatorships and at the time American troops were first sent to Korea in July 1950, the mission was to drive the communist North’s forces out of South Korea. Under President Harry Truman’s expanding policy aims—encouraged by MacArthur’s daring landing at Inchon—it became a war to liberate the North from communists and reunify the Korean peninsula.

Once Americans crossed the 38th parallel—the border that divided South and North Korea—and headed north toward the Yalu River, the border between North Korea and China, the threat of a war that included communist China became a reality. Truman had wanted to avoid a war with China. He and MacArthur disagreed and in April 1951, Truman fired MacArthur for insubordination.

Siler joined his unit in South Korea after that. Battles on the front lines continued along with political negotiations to put a stop to the fighting. It was Siler’s first time overseas. He recalls how vastly different the countryside was in South Korea as compared to the North. It was definitely a change of scenery for a country boy from North Carolina. “It wasn’t until we got up along the demarcation line that we got into the mountains,” he says. “That wasn’t so nice. I hadn’t been there too long when I first saw combat.”

A piece of shrapnel from a mortar round to the shoulder and arm put Siler out of action for a month and a half. According to Korean War records in the National Archives, Siler was “seriously wounded in action by a missile” Dec. 3, 1951. He was sent to a hospital in Pusan, on the southern tip of Korea. The shrapnel was removed. After he healed, Siler was sent back to the front lines. “I thought maybe that was going to send me home, but it didn’t,” he says. “I would have hated to leave some of my buddies in the outfit.”

He returned to his unit, once again treading through rice paddies on night patrol. “If you didn’t dig a fox hole, a trench or a bunker to get in, you were mostly unprotected,” he says. One night while on patrol, a fellow soldier hit a trip wire that set off an explosion. Siler was injured again. He was sent to a Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) unit. “It wasn’t serious,” he says. “They had to remove some lead from me. It wasn’t as bad as the first time.” Siler returned to combat again and was in Korea for about 15 months total. “I was in combat the whole time,” he says. “We were making progress.” In total, nearly 40,000 Americans died and more than 100,000 were wounded in the war.

He returned to his unit, once again treading through rice paddies on night patrol. “If you didn’t dig a fox hole, a trench or a bunker to get in, you were mostly unprotected,” he says. One night while on patrol, a fellow soldier hit a trip wire that set off an explosion. Siler was injured again. He was sent to a Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) unit. “It wasn’t serious,” he says. “They had to remove some lead from me. It wasn’t as bad as the first time.” Siler returned to combat again and was in Korea for about 15 months total. “I was in combat the whole time,” he says. “We were making progress.” In total, nearly 40,000 Americans died and more than 100,000 were wounded in the war.

Meanwhile on campus, news of the war reached students mostly in the form of letters. One such letter written by Cpl. James L. Hamrick ’55 to head basketball coach Doc Mathis was printed in the Maroon and Gold in 1952. In addition to receiving news directly from the Korean front, students were encouraged to write to Hamrick, who had been a star forward on the basketball team and a pitcher on the baseball team. He was inducted into the Elon Sports Hall of Fame in 1973. He died March 4, 2010, in Roanoke, Virginia. He served as a section leader for two .50-caliber machine guns, a job he preferred over being a rifleman, according to the letter. “It isn’t a soft job, but it sure beats being a rifleman. Boy, I mean those riflemen really catch it,” he wrote.

Similar to Siler, he spent a lot of time in the mountains. “I thought those mountains up in western North Carolina were big, but they are just foothills compared to some of these over here,” Hamrick wrote. “You would never believe it until you see some of them. You have heard of people going to the mountains for a vacation, but by golly, I never want to see another mountain, much less climb one.” Time in the war also had inspired Hamrick to make sure he applied himself more once he returned to Elon. “Boy, if I knew when I was in school what I know now, you couldn’t have kept my nose out of the book, but that’s the way the ball bounces.”

Lessons learned from the past are a clear indicator that it is unlikely that today North Korea’s leader, Kim Jong Un, will give up the country’s nuclear weapons. “There’s a generally held view that long range nuclear weapons aren’t really good for anything other than preventing war and deterring an adversary,” Kirk says. “The thinking in North Korea seems to be, ‘the U.S. will never hit us if it knows we can hit back.’”

North Korea has tested more than 80 missiles in recent months, and Kim is trying to figure out President Donald Trump, who has said that North Korea’s threats will be met with “fire and fury.” What that might look like remains to be seen. “It’s one thing to talk tough and engage in tough rhetoric,” Kirk says, “but when you run through all the U.S. war fighting scenarios, you likely end up in a place where past presidents have been: all the options are terrible.”

There does seem to be a sense of paranoia on both sides. “Is what we are perceiving real or a game of mirrors?” Kirk says. “If we had a different president, there is no reason to think this issue wouldn’t be at the top of the inbox. We can fall into thinking this is all about Trump and his style, which isn’t the case, but it does take a difficult situation and makes it more complicated.”

There does seem to be a sense of paranoia on both sides. “Is what we are perceiving real or a game of mirrors?” Kirk says. “If we had a different president, there is no reason to think this issue wouldn’t be at the top of the inbox. We can fall into thinking this is all about Trump and his style, which isn’t the case, but it does take a difficult situation and makes it more complicated.”

Kirk says a lack of experience with national security and defense policies for the leaders in both countries also adds to the unpredictability of the current situation. Prior to his presidency, Trump was a real-estate mogul and reality-TV star, and Kim is a third-generation dictator who has never met a head of state. They have about seven years of political experience between them and six are on the North Korean side. Regardless of his experience, it’s a foreign policy dilemma Trump inherited, like the presidents before him. “There was never any real resolution to the Korean War,” Kirk says. “The North Koreans are still fighting it, and I guess whether we realize it or not, so are we.”

While all eyes are on North Korea right now and Kim’s next move, Kirk questions whether the threat of a nuclear strike by either side is imminent. “I won’t be surprised if we are in a different position by the end of 2020,” he says. “And we will say, ‘What was that crisis about?’ We are focusing so much attention on it right now but how different is it really than the Chinese’s development of nuclear weapons a half century ago? The North has steadily pursued its nuclear and missile programs for years, and no U.S. administration has found a way to stop them.”