Students in HSS 349: Violence in Families classes take knowledge to area high schools, empower students to end cycles of abuse.

What is consent? What are the signs of abusive relationships? How should we help if someone we care about is in trouble?

These are questions many adults grapple with, but Alamance County teens are finding answers sooner thanks to the work of Elon University students.

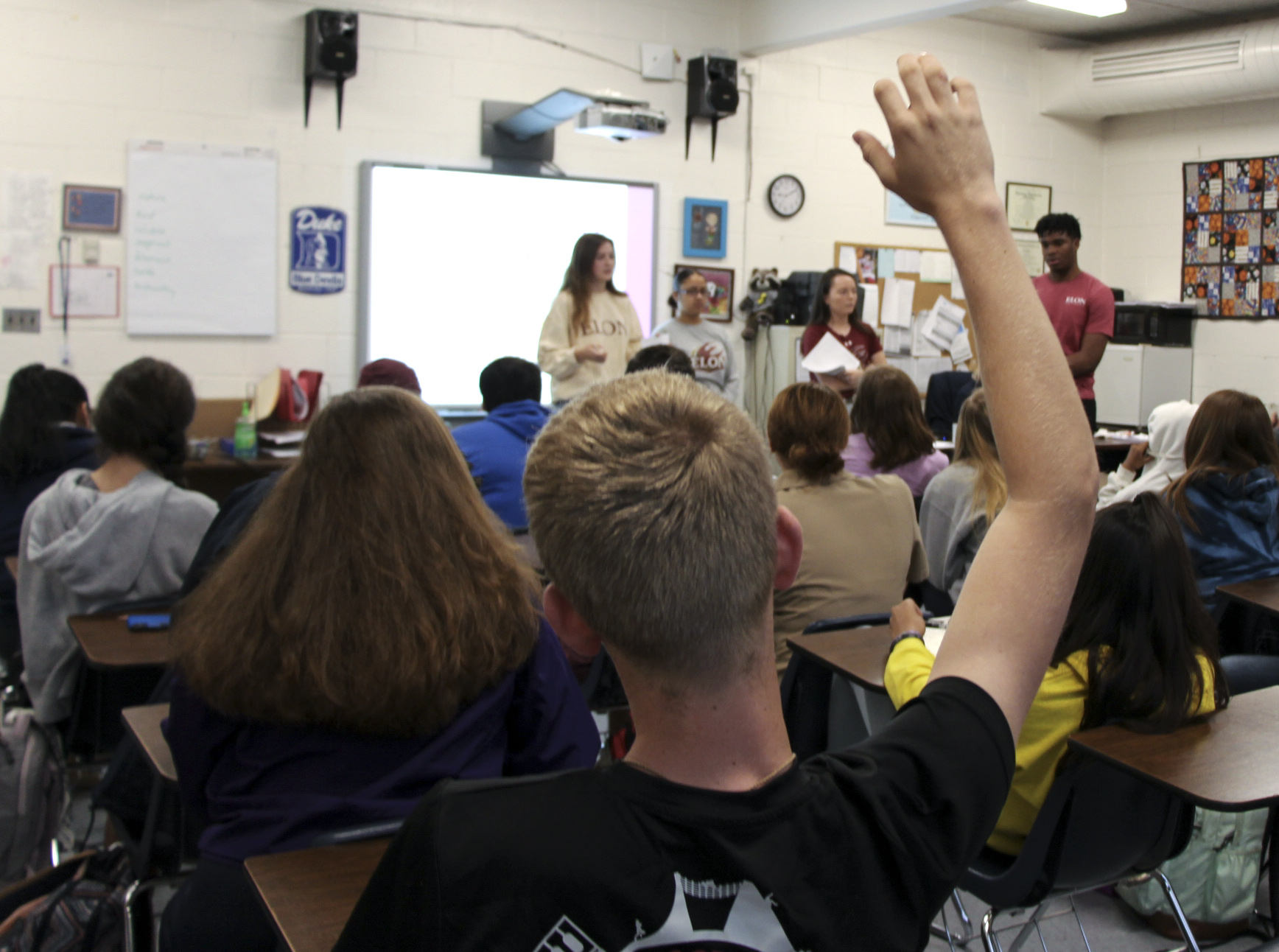

Each fall, students in Angela Llewellyn Jones’ Human Service Studies 349: Violence in Families class work with Family Abuse Services of Alamance County to bring the Mentors in Violence Prevention program to first-year students at area high schools. The course opens dialogue around problem-solving to empower students to become active agents against relationship abuse, harassment, and sexual assault.

The MVP program was developed in 1993 by Jackson Katz at Northeastern University to teach harassment and violence prevention through sports. The program expanded for use with a broad range of audiences – from teenagers, to military and corporate training. For youth, MVP uses statistics about teen abuse and assaults, gives information about types of abusive behaviors and confronts students with scenarios that aren’t always black-and-white.

“If a woman hits a man, is it OK for him to hit her back?”

“What would you do if a friend sent you a nude photo of an ex?”

“If a man and a woman are both drunk and they have sex, is that rape?”

Those kinds of questions lead to surprisingly frank conversations around sensitive topics.

In Lance Huff’s health and P.E. class at Western Alamance High School, questions about sexual consent evolved into a discussion of North Carolina laws, the risks of having sex if one or both partners have been drinking (risky at best, and potentially grounds for a rape case), and whether a person can revoke consent during a sexual act (they can).

That college students are the ones providing the information is what makes the program so powerful, educators say. And that teenagers learn about healthy relationships early makes it more likely to stop abuse or assaults before they happen.

“What I really like about it is that it uses a peer-education model,” said Bridget Werner, Family Abuse Services prevention coordinator. “The topics covered are heavy, and it’s a lot easier to be received coming from someone closer to their age. (High school students) are taking in the information and messages at a rate that’s better than when it just comes from teachers.”

The MVP program supports high school curriculum around healthy relationships and sexual violence, Huff said, “but hearing it from someone other than a teacher or an adult they always hear it from helps.”

Because MVP might offer the first educated, serious discussion around issues and legalities of sexual consent, it’s especially valuable that college students can lead those conversations, Werner said.

“Having these conversations as early as possible allows them to have the information they need. Hopefully we can change behavior before it ever happens,” Werner said.

The program wouldn’t exist in Alamance County’s schools or through Family Abuse Services without Elon students.

Elon’s participation in the MVP program grew out of a kind of necessity, Jones, associate dean of Elon College, the College of Arts and Sciences, and associate professor of social justice, said.

Students in Violence in Families confront traumatic, deeply affecting issues with no easy solutions: child abuse, elder abuse, domestic violence, abuse and violence between siblings. Jones taught the course several semesters and saw the toll those issues and cases they study were having on students.

So she decided to include MVP facilitator training in the course and deploy students to area high schools. Something clicked.

“MVP really helps them emotionally with the weight of the course topics,” Jones said. “Sending them out into the high schools to take what they’re learning and turn it around and be empowered by it helps them. And hopefully, even if we only reach one kid about a red flag, that gets their attention and it changes their life. The seeds we’re planting at the schools are so empowering.”

Students feel that relief, but in training for MVP, they are confronted with troubling statistics. One in four girls and one in nine males ages 11-14 experience relationship abuse or sexual assault. Though three-quarters of teens and pre-teens say they would reach out to a friend or adult for help, fewer than 25 percent actually do.

Lily Dresner ’22 said the “gravity and extent” of the issue among teens surprised her. She hopes the program increases conversation around abusive relationships and creates “a culture of education” around the topic.

One of the keys of MVP is making bystanders – especially friends and relatives – see ways they can intervene to stop abuse. The course teaches teens about direct intervention, distracting an abuser to diffuse a situation, and delegating the handling of harmful scenarios amongst friends and trusted adults.

Several students in this semester’s HSS 349 course said MVP’s clear guidelines about control, power and abuse in relationships showed them how to help friends and recognize signs in their own lives.

“For example, controlling is not caring,” said Chantell McCall ’22. “I’m not sure I’d thought about that directly before.”

Werner particularly appreciates that MVP’s group instruction allows Elon students to interact and converse with each other as they present the materials.

“They all have different take-aways from the lessons, and different ways of describing and relating to the material,” Werner said. “Students see them interacting with it and learning from it, and it becomes an ongoing process.”

“This has been a good opportunity to partner with Elon,” Werner added. “And it builds on conversations we have with students (in an eighth-grade anti-bullying and-sexting program). It’s a goal of mine to have something like this for students during each year of high school.”

As for Elon students, HSS 349 and MVP have given them skills they plan to carry with them throughout their lives.

“I’m so glad that I’m in this class. You just learn to be a better human being,” said Rose Lehrman ’21. “You learn how to look out for one another, not just because you know rules and facts in a concrete way, but from an emotional and sympathetic standpoint. It’s about human decency.”