Grand Challenges I is a required first-semester course for engineering majors, delving into problem-solving for a better future. Students built and used remotely operated vehicles to complete a variety of underwater tasks.

Fifty-nine plastic zip ties held a PVC pipe-framed, remotely operated underwater vehicle together as it awaited its maiden voyage on the edge of Beck Pool on Friday afternoon.

They were crisscrossed around every joint, holding various wires in place, jury-rigging three motorized propellers to the frame and steadying multifunctional arm.

Just before Catherine Capodanno ‘23 lowered it into the water — where it would seek to tag a plastic model of a whale shark, maneuver through an obstacle, collect floating debris and take measurements and readings in the pool’s deep end — she used a 60th zip tie to affix a camera to the vehicle.

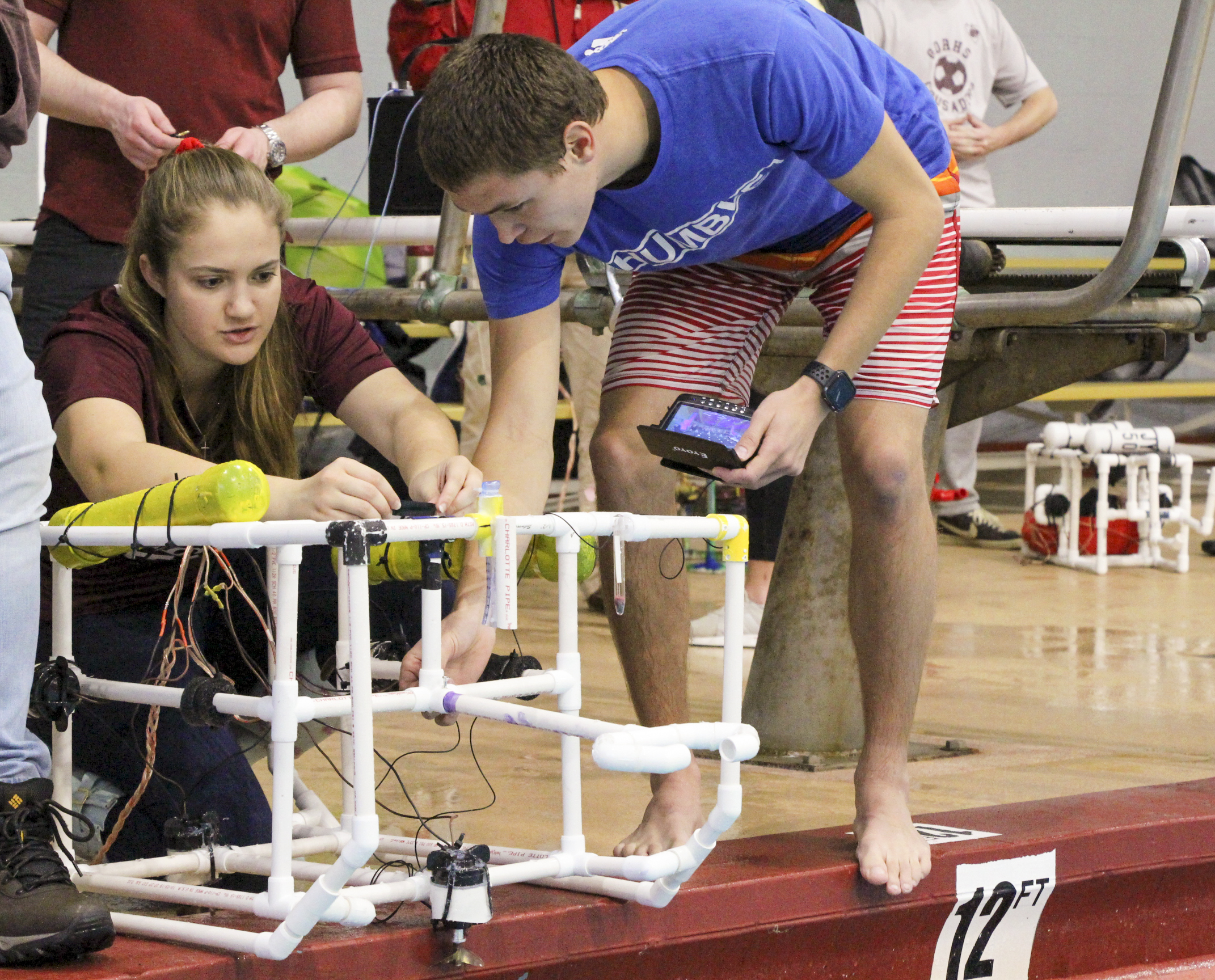

But not even 60 zip ties are enough. The vehicle comes unhinged as it enters the pool. Capodanno and her partner Perrin Craig ’23 hoist it onto the deck and quickly make repairs. Another dozen or so plastic ties are added as Associate Professor of Engineering Scott Wolter looks on, handing them tools as needed.

This is the final for EGR 121: Grand Challenges in Engineering I, the required entry level course for Elon’s first-year engineering students that operates as a survey of and introduction to basic principles and the National Academy of Engineering’s 14 identified Grand Challenges to humanity’s survival.

The course is built on team problem-solving and a series of projects that build the tangible and intangible skills engineers need in the real world.

“A lot of it has been trial and error. You make a mistake and you fix it on the fly,” Capodanno said. “I wasn’t really sure about engineering when I came to Elon. I thought a lot of it was math. This class made me realize engineering is a hands-on thing. It’s working with a team, not just doing a math problem.”

Students echoed Capodanno as vehicle after vehicle entered the pool, cruising below the surface and ticking off the tasks required for the final. The vehicle designs varied, though were mostly cubed structures with various arms or cradles for housing necessary equipment. Some were large enough to need two people to carry.

Graham Young ’23, Xander Nostrand ’23 and Megan Sassaman ’22 built a fairly compact vehicle to control the weight of its skeleton and reduce the number of propellers needed. They built a floating spool of string to measure water depth. They attached a thermometer to measure water temperature. They agreed that solving those design problems together resulted in a better structure, and they could see how that process will aid them in their careers at Elon and afterward.

After watching about seven student teams’ vehicles fulfill the final’s five objectives, Wolter said the introductory emphasis on teamwork and projects is intentional at Elon.

“When they leave this class, they see things differently,” Wolter said. “It’s great for them to have to fix things like this, on the fly. It teaches them so many intangible things that you can’t teach in a classroom. They have to experience it and work together.”

Where other universities might corral first-year engineering students in large classrooms to solve math and physics problems, Elon’s engineering program is focused on sharpening the ways students relate to the material and each other. Yearly required Grand Challenges courses use the National Academy of Engineering’s 14 Grand Challenges for Engineering in the 21st Century as springboards.

Among other things, the NAE’s 14 challenges include access to clean drinking water, creating better medicines, securing cyberspace, and improving humanity’s use of energy and environmental impact on the planet.

Grand Challenges I and the remotely operated vehicle project sets the stage for students to progressively tackle those challenges as they advance toward graduation. It also makes the first semester in the program a little bit more fun than it might be otherwise, Wolter said.

“They are bonding with each other,” Wolter said. “We’re trying to provide them some perspective on engineering. The Grand Challenges courses give them that and show them why you would want to be an engineer.”