The issue began as a 2018 College Art Association conference panel Ringelberg organized around transgender art.

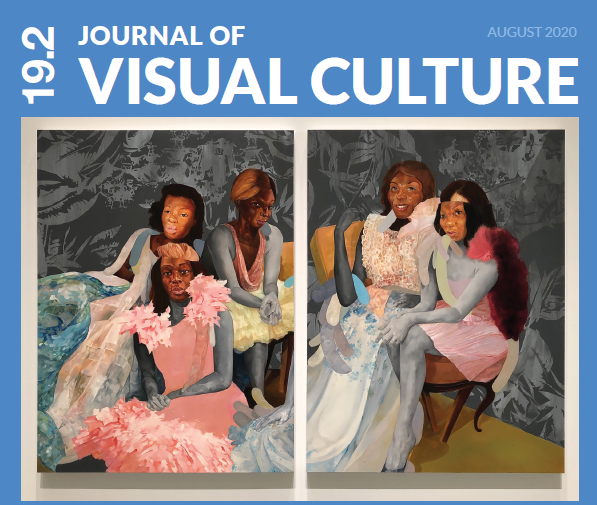

The latest issue of the Journal of Visual Culture , co-edited by Professor of Art History Kirstin Ringelberg, aims to expand views and understanding of transgender art and culture.

Through analysis of historical photographs, film, paintings, sculpture and even modern-day prosthetics, the articles grapple with visibility, cultural violence, belonging, and the complex variations of gender nonconformity.

“… Our goal is that the picture these contributions present as a group is even greater than that they present individually, imbued with the spirit of aspiration, of memory and projection, the shading of loss, the wily cleverness of survival, the refusal of regulation, the kinship of community, the demand to be seen (or not!) but on our own terms,” Ringelberg and co-editor Cyle Metzger, a Ph.D. candidate at Stanford University wrote in the issue’s introduction.

The issue began as a panel on transgender art that Ringelberg organized and co-chaired at a February 2018 College Art Association conference. It was the first such panel around transgender art within the CAA and academic field. That discussion led to Ringelberg first gathering and editing a collection of articles for the Journal of Visual Culture with Metzger to eventually curating an entire issue at the journal’s request.

“We in the U.S. act like we just discovered that trans people exist,” Ringelberg said. “As a historian I want to challenge that case. It’s pretty easy to do: There are lots of people in history we could call trans, though it would be an anachronism to use that language. It is a challenge of how to think through these issues in our own time and also do justice to the time period. Some articles wrestle with that: How looking at and creating archives from a perspective of being trans-inclusive, being detectives in those archives for codes we might recognize that others might not.”

The journal’s founder and editor-in-chief, Marquard Smith, welcomed an analysis of the “incredibly complex and urgent subject matter of transgender art and visual culture” for a full issue and lauded Ringelberg and Metzger for their ambition. Smith believes the breadth of the angles and ideas covered in the issue define “the terms and conditions by which we’ll engage with debates on transgender art and visual culture for years to come.”

Ringelberg and Metzger took pains to structure the articles within the journal to be read in sequence, with a through-line of themes and considerations. They were especially careful to create an analysis that broadened the scope of transgender art and visuals rather than constraining it to a monolithic construct, Ringelberg said.

“It really mattered to me. I really want people to do something that nobody does in 2020, which is read the entire journal, cover to cover, in order,” Ringelberg said.

Smith believes the contextualization of trans visuals should guide future study of art and art history.

“If (academic disciplines) take what Kirstin and Cyle have done here seriously, which they would, which they must, they can never be the same again,” Smith said. “And, to be honest, anything short of this would be awfully disappointing! Kirstin and Cyle and all the contributors have thrown down the gauntlet, and all of us are obliged, I believe, to pick it up. How could we not?”