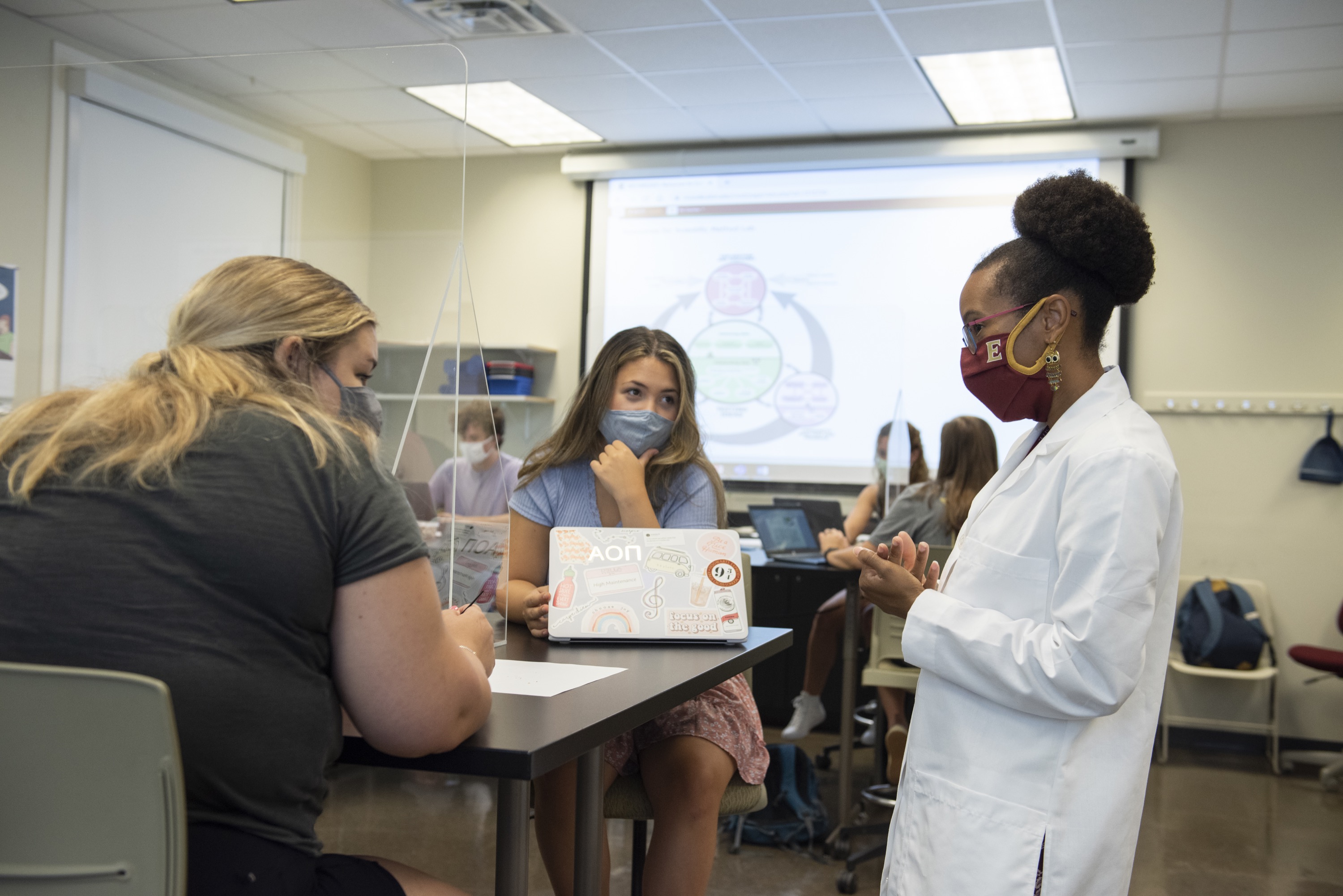

Blending in-person experimentation with remote methodologies, faculty have changed the way labs operate while meeting learning requirements.

Labs are fundamental to the study and practice of science, but how do you run them — grouping students to experiment and gather data — at a time when physical distance is a necessity?

Even tougher: How do you run labs remotely with access to required materials and instruments?

Elon’s science faculty set about solving these problems this spring and summer and found solutions tailored to each branch’s and class’s goals, space limitations and materials. That wasn’t easy.

Faculty in the Biology Department spent the summer examining lab spaces — each is a little different — and determining the best ways to meet course needs and maximize time with students while being safety conscious, said Associate Professor Antonio Izzo.

For his cell biology labs, Izzo has split classes into two groups that spend half their time in the lab with him and the other in virtual sessions working on related problem sets with a teaching assistant. Students complete reading and assignments before lab.

“When they’re in the lab, it’s all about as much hands-on work as possible,” Izzo said. “They’re engaging with the scientific process in very much the same way as before. It’s about hands-on discovery, a lot of talking through problems when things don’t work and answering questions non-stop. That’s when you’re doing real science.”

In his lab, stations have been separated to allow him to get close enough to assist students without getting too close. After collecting data individually, students meet virtually with groups for analysis, observations and discussions.

“They’re collating all their data, and they’re getting a replication of data that they didn’t have before when they were working together inside the lab,” Izzo said. “Now they can talk through differences in their data and that process looks really promising.”

“They’re engaging with the scientific process in very much the same way as before. It’s about hands-on discovery, a lot of talking through problems when things don’t work and answering questions non-stop. That’s when you’re doing real science.”

Associate Professor of Biology Antonio Izzo

In the Chemistry Department — where up to 40 students normally are in the introductory lab together — faculty and teaching assistants had to get creative. The aim was efficiency of operations and flexibility for remote learning.

Students usually work in groups of four conducting the experiments and logging results. This semester students work individually, 10 at a time in the lab. Those groups rotate through the lab by week, virtual for three weeks and in-person the fourth week, said Associate Professor Dan Wright.

Faculty worked with teaching assistants over the summer to record videos of each experiment students would be assigned during the semester. Those videos show closeups of scientific instruments, which remote students use to read and record measurements from.

Wright described one of the labs, a “crime scene” where a credit card was used to break in a lock. Students are tasked with determining which type of plastic the card was. The tests are observational, even in-person: which color a plastic burns, whether the smoke is acidic, and examining the density of the smoke. The videos show the plastic-burning during tests, and students note their observations to determine the type of plastic.

“We usually want them to come in a little blind and learn as they go and not get direct instructions. We want them to discover what’s going on,” said Wright, who devised the system with Assistant Professor Anthony Rizzuto. “Now we have to be a little more direct. Though they aren’t doing the measuring physically with their hands, they have to read all the instruments and take all the measurements. They are still getting the lab experience and the experiential exposure that we need them to have.”

“They are still getting the lab experience and the experiential exposure that we need them to have.”

Associate Professor of Chemistry Dan Wright

Inside the Duke Building Robotics Lab, computer science and engineering majors continue to program sensor-controlled robotic vehicles this semester, just to a smaller scale than usual.

Senior Lecturer in Computer Science Joel Hollingsworth and Associate Professor of Physics Kyle Altmann realized the 2-square-foot, group-built and programmed vehicles wouldn’t be possible this semester. Instead, each student has a smaller robot built from a kit rather than previous, larger vehicles. That means no equipment sharing and less worry about sanitization.

But the lab experience is the same. The vehicles still have to be programmed to account and correct for real-world forces, travel distances, make turns, and use programmed sensors to complete various tasks.

In the Physics Department, Altmann piloted all-remote labs this summer. He’s using that same system this semester. Each student has their own kit of materials and has the option of completing the lab assignment at home or inside the lab. He estimated that about three-fourths of his students have opted to be in the lab so far.

“If we have to go completely remote, we’ve got everything we need to continue,” Altmann said. “We can keep right on going.”

“If we have to go completely remote, we’ve got everything we need to continue.”

Associate Professor of Physics Kyle Altmann

On the roof of Alumni Gym, the undergraduates in astronomy lab are still stargazing — just in more regimented and slightly scaled-back ways, says Professor of Astrophysics Tony Crider.

In previous semesters, as many as 10 students could be on the roof manning telescopes in pairs. The timing was on a first-come, first-served basis, and students congregated to wait their turn in a room below. This semester, only three at a time are allowed on the roof. Students in the introductory astronomy course make appointments to use telescopes, and teaching assistants help monitor the system and clean telescopes between uses. About 150 students are enrolled in this semester’s astronomy courses. Crider oversees them all in the lab.

Due to the numbers, the restrictions of astronomy labs generally (it must be clear and relatively dark), and the simple fact that some students will have to complete lab assignments remotely this fall, Crider has integrated more apps, technology and independent observation into the course. That includes a project tracking the sunset over the course of the semester from specific locations on and off campus.

“The goal of the lab is to get them looking up more, to be aware of the sky no matter where they are, not only on top of the gym,” Crider said. “This semester has meant doing now what I thought we’d be doing five years from now.”

In a society where viewing experiences on screens is often the only option, students are finding extra value in being able to observe the cosmos with their naked eyes.

“Jupiter and Saturn are visible now. Students are always impressed when they can see that, but this semester there seems to be a little more ‘wow’ that they can see these things not just through a screen, but by actually being somewhere and doing something,” Crider said. “Seeing that light with your own eyes is really important.”