The survey conducted by Assistant Professor David McGraw of more than 3,000 workers in the performing arts industry delved into how they are coping during the pandemic, whether they are likely to leave the field and how the industry may be changing.

During a time when the COVID-19 pandemic has turned the lights off on Broadway and pulled the curtains closed on stages across the country, the performing arts as an industry is reeling. How are the individuals — the set designers, stage managers, the performers and everyone who makes a show come to life — faring during such a challenging time, both creatively and professionally?

That’s what Assistant Professor of Arts Administration David McGraw and his research partner, Meg Friedman, set out to determine earlier this year. After adapting McGraw’s longstanding survey of stage managers, McGraw and Friedman solicited responses from more than 3,300 individuals in a broad array of roles within the industry.

Conducted in July with the results published this fall, the “Return to the Stage” survey found that while the workforce in the performing arts industry is traditionally adaptable, resilient and loyal to the industry, workers were experiencing profound stress that could, over the longer term, result in many leaving the field all together. Part of that, McGraw said, is that there’s not a clear path forward or a timeline for the performing arts industry to re-emerge if and when the pandemic subsides.

“It’s not as if we’re on pause and things will just be back to normal in the near future,” McGraw said. “There are so many steps to the reopening, and we’re not even confident in predicting what it might look like a year from now.”

The survey came about after Friedman, a consultant and former stage manager, reached out to McGraw about the latest edition of his stage manager survey, which he has been conducting since 2006, that was published in just as the pandemic was ramping up. They observed that while there were studies delving into the economic impact of the pandemic on performing arts, there was little being done to gauge how the pandemic was impacting the workforce on a more personal level.

“Whether you’re a performer, or in construction or administration, we all have a very high tolerance for risk just being in this industry,” McGraw said. “You don’t get into the performing arts looking for stability. But we wanted to know how people were doing with the additional stress, how they were coping with it, what they were doing to make do and get by, and what long-term impacts this will have on the health of the industry.”

“Whether you’re a performer, or in construction or administration, we all have a very high tolerance for risk just being in this industry,” McGraw said. “You don’t get into the performing arts looking for stability. But we wanted to know how people were doing with the additional stress, how they were coping with it, what they were doing to make do and get by, and what long-term impacts this will have on the health of the industry.”

Additionally, given the mounting national conversations around race, they wanted to see how the pandemic might be impacting minority groups differently. “We have a whole industry that is unable to do their day work, and they can be more reflective,” McGraw said.

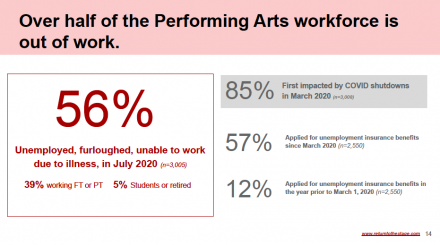

Conducted July 1-14, the survey found that 56 percent of performing arts workers were unemployed, furloughed or unable to work due to illness, while 39 percent were working full- or part-time and the remaining 5 percent were students or retired. Eighty-five percent were first impacted in some way by the COVID-19 shutdowns in March, the survey found. A majority — 59 percent — traditionally make all of their income from work in the field.

The survey mirrored questions asked in the Household Pulse analysis by the U.S. Census Bureau to see how performing arts workers were coping emotionally compared to the general population. These workers were more likely to report frequent mental health impacts from the pandemic than the general population, and have adopted strategies to support career development and learning during the pandemic. The survey found that many in the field — 46 percent — took up mental coping strategies such as mindfulness or meditation since they started their career in the performing arts, indicating that those engaged in the field may have already cultivated their ability to be resilient during challenging times.

The survey found a level of optimism that the business of performing arts would be able to adapt over time, with many saying they believe this is an opportunity to make the workplace culture and performances themselves more accessible financially and technologically.

Looking ahead, the survey found that the percentage of respondents who are “extremely likely” to leave the field has increased five-fold since COVID-19 began having an impact on the industry. Similarly, 61 percent said that prior to COVID-19, it would have been “extremely unlikely” to leave the field, but that since they pandemic, that number had fallen to 23 percent. The likelihood that workers would leave the field increased across all levels of tenure, but that increase was most pronounced among those who were newest to the field and those who were in the middle of their careers.

“It was certainly disheartening to see how beaten down individual workers in the performing arts have been, and to see the impact the pandemic has had on their mental health and resiliency,” McGraw said.

McGraw said he is also concerned about younger workers — those who were just beginning their careers, or students who are preparing for their careers in performing arts. How that pipeline of new workers is impacted by the pandemic could have long-term consequences for the field. “That’s the big worry,” McGraw said. “If you had just graduated, and you were unable to move directly into the performing arts — will those people return, or will they have moved on and found a different career path?”