The Committee on Elon History and Memory begins to paint a more inclusive picture of Elon’s past.

Walk across Elon’s campus and you see tributes to many of the people who shaped the university’s success throughout its history. You see it in building names, plaques and portraits. William A. Harper, Elon’s fourth president, seemed a worthy candidate for such an honor in 1968 when the Harper Center residence complex was built. When it was demolished to make way for the Global Neighborhood, his name was added to one of the residence halls in the Colonnades Neighborhood. His association with the university dates to the late 1800s when he was a student, through stints as a professor, dean and ultimately 20 years as president. He shepherded Elon through a tumultuous period that included World War I, the 1918-19 flu pandemic and the 1923 fire that destroyed most of campus.

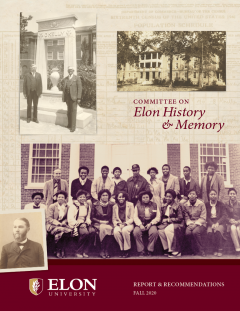

But a deeper look at Harper’s past reveals a more complex legacy beyond his accomplishments, one that includes evidence of racism. It’s an all-too-common scenario that is playing out on campuses across the nation, prompting many institutions to explore untold stories that have been obscured or suppressed in traditional historical narratives filtered through a White lens. It’s one of the main reasons why President Connie Ledoux Book announced in 2018 the formation of the Committee on Elon History and Memory. Since then, a university-wide committee of 12 faculty, staff and students has been examining Elon’s institutional history “in a transparent, participatory and intellectually rigorous manner.”

“I think the first and most important step is acknowledging it, discussing it and owning the truth of it,” Book says. “That self-knowledge is critical for institutions and individuals. This effort shouldn’t be perceived as a negative; in fact, I feel positive about it, about the fullness of a history we are missing, stories that will help us connect to each other and be agents for change. Without a full history, we are more likely to not make progress, or even worse, make the same mistakes.”

After two years of work, the committee released a report in October centered on the idea that telling a more complete version of the past offers the opportunity to create a more inclusive future. “If we really want to be a place characterized by excellence, diversity and inclusion, we need to be attentive to the ways in which we send signals not just with our words but with the stories we tell about ourselves, with the people and things we remember, and with the stories we lift up through commemorative practices,” says Charles Irons, William J. Story Sr. Professor of History and chair of the Committee on Elon History and Memory.

***

Harper’s story illustrates how critically important it is for Elon to reckon with its past. In a 1910 editorial in The Christian Sun, Harper expressed alarm at the growing number of Black students pursuing a college education. “Our white supremacy does not rest on and cannot be maintained by brawn,” Harper argued in the editorial. “It now rests on and must ever be maintained by brain power, mental astuteness, mental skill, and intellectual acumen. The history of the world shows that education is essential to race leadership and the negroes are willing to sacrifice more for it than are our whites.” He also invited readers to contact him directly “for particulars and terms according to which [Elon] undertakes to foster individual and racial supremacy.”

A decade later, Harper was identified in a 1920 article in the Raleigh News & Observer as the leader of a posse to apprehend John Jeffress, a Black man accused of sexually assaulting a 7-year-old girl. A trial was arranged the same day with Harper set to serve as a witness, but before the trial began, the article states, a mob of unidentified armed men dragged Jeffress from the jail and killed him. Harper’s role in the events that led to Jeffress’ lynching sparked an online petition this summer calling for the removal of the Harper Hall name. It was something the Committee on Elon History and Memory was planning to recommend in its report as well. But when President Book learned about the 1910 editorial, she shared it with the board of trustees, and they collectively agreed to immediately remove his name from the residence hall in July. “At one point in his career at Elon, [Harper’s] writings advocated that White people pursue higher education as a way to maintain their racial supremacy over Blacks,” Book says, adding that she will be appointing a group to review his writings to gain a fuller understanding of his life’s work. “These views are racist and at odds with our mission.”

***

The purpose of the committee’s work is twofold: to critically examine specific events and individuals in Elon’s past and how those histories have been recounted and commemorated over time, without serving as gatekeepers of Elon’s history or producing an “authorized version” of events. With that in mind, the committee reviewed some established historical narratives as a starting point, like “Elon College: Its History and Traditions” by former Professor of History Durward T. Stokes, a 1982 book that, the committee’s report notes, neglects to include the experiences of Black students at the university. From there, the committee identified areas for further study. Irons says committee members and university archivists Chrystal Carpenter and Libby Coyner as well as student researchers were integral in collecting and analyzing historical documents throughout the process. The group also consulted “From a Grove of Oaks,” a book published in 2014 by former University Historian George Troxler, and especially benefited from “Elon’s Black History: A Story to Be Told,” which L’Tanya Richmond ’87 wrote in 2005 as her master’s thesis at Duke University.

“A lot of this information has been out of the limelight, not front and center,” says Randy Williams, vice president and associate provost for inclusive excellence. “As it becomes more visible, we have to assess how does this information that we’ve learned align with who we are as an institution, and how to respond to information that may not be aligned with our mission and values.”

As the committee members researched best practices from other universities conducting history and memory work, they discovered that the bulk of current scholarship focuses on race. They decided to concentrate their initial efforts on the Black experience at Elon — both anti-Black racism and Black achievements that have been only partially told or erased. But Irons says the committee hopes its process will serve as a template for conducting similar work related to other identities at Elon, including sexual orientation, gender identity, ethnicity, religion and socioeconomic status. “Given the energy of the field and the fact that in the context of the history of the American South, race is the most salient aspect of differentiation and exploitation, it seemed appropriate to start with that,” Irons says. “But we want to be emphatic that we know it’s not the only aspect of identity and we know there is additional work to be done.”

The committee’s report details 10 “episodes” related to Black history at Elon, including a deeper look at Harper’s work. Previous research about Harper, Irons says, suggests that his views on race changed over time. From 1926 to 1929 he served as chairman of the Board of Control of Franklinton Christian College, the Christian Convention’s school for Black students in North Carolina. He also called for an end to “racial hatred,” and a convention held at Elon during his tenure as president invited students from Black schools to engage in interfaith dialogue with representatives from White schools. But, Irons believes, these positions did not indicate a dramatic shift. Many Southern White progressives came to promote education for Black students, as long as the schools were segregated, and their purpose was to assimilate Black people into subservient stations in American life.

Irons says the Harper example raises questions about what aspect of a person is being celebrated when universities commemorate them with a building name or monument, and what message that conveys to the community. It’s a complicated process. “We are still learning how to acknowledge the positive contributions of people like Harper, who rebuilt Elon after the fire, while recognizing that his legacy of strident White supremacy is inconsistent with our values,” he says. “But we’re not trying to erase the memory of Harper. To the contrary, we want people to know more about him than they’ve ever known. That’s the point of all this: to learn about our own past.”

***

Now that the committee’s two-year term is over, the report includes recommendations for ways the university can continue the work as part of its broader diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives. Among the suggestions are establishing a permanent version of the Committee on Elon History and Memory and supporting the new Black Lumen Project, an equity initiative specific to the Black experience. In 2019, at the recommendation of the committee, Elon joined Universities Studying Slavery, a consortium of nearly 70 institutions that stemmed from work at the University of Virginia in 2014, and seeks to address both historical and contemporary issues related to race and inequality in higher education. The Black Lumen Project evolved from Elon’s Universities Studying Slavery subcommittee and aims to build on existing work related to the Black experience at Elon in collaboration with the Center for Race, Ethnicity and Diversity Education and African & African-American Studies at Elon University.

It’s going to be hard, it’s going to be uncomfortable, it’s going to be a long haul, but we have to engage in it. By understanding the history, we can understand how we got to where we are and how we might go into the future differently so we can create a truly inclusive environment, one where we’re getting closer and closer to humanity.

Other recommendations include implementing a new process for the renaming of spaces on campus; developing new commemorative practices around a more inclusive version of Elon’s history, such as oral history projects and tours about the Black experience at Elon; and creating multiple pathways for students to confront race in their coursework.

This summer, Book called on faculty to revise the curriculum and require students in all majors to take courses anchored in equity and inclusion. “We use language about the ‘Elon bubble,’ but Elon is not on an island by itself,” Williams says. “It’s connected to and part of the greater society, and racism was and is a huge part of this society. When you see something that’s so ubiquitous of a construct as race and it affects us in so many ways, I feel that we should all be studying this.”

Williams says that Elon’s racial equity work is personal to him as a Black man because it has real-world implications for him and many people he loves. He hopes the committee’s findings and the continuing diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives that result from them will make it more personal for people across all identities. He hopes that studying a broader array of voices from Elon’s past will foster deeper understanding and empathy. And he hopes that acknowledging and learning from the greater truth of Elon’s history will pave the way for healing and a more just future.

“There is a toll that people feel when we talk about race,” Williams says. “But until we get back to that truth and reconciliation, we have to confront it. It’s going to be hard, it’s going to be uncomfortable, it’s going to be a long haul, but we have to engage in it. By understanding the history, we can understand how we got to where we are and how we might go into the future differently so we can create a truly inclusive environment, one where we’re getting closer and closer to humanity.”