Renewing our commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion at Elon and beyond.

The year is 2020. The world is being ravaged by a pandemic with no end in sight. For the first time in most of our lives, we are united under the threat of an unknown disease. Then, in May, the eyes of the world fall on Minneapolis. That’s when a 46-year-old Black man is arrested for allegedly buying cigarettes using a counterfeit $20 bill. That’s when a White police officer decides to put his knee on the suspect’s neck, for eight minutes and 46 seconds, while two other officers watch and bystanders helplessly record the incident with their cellphones. That’s when George Floyd dies, and the world is never the same. Protests across the country and the world ensue. So does media coverage of other alleged police brutality cases against members of the Black community, some of which took place before Floyd’s death.

Atatiana Jefferson.

Ahmaud Arbery.

Breonna Taylor.

Rayshard Brooks.

Calls for justice and police reform are heard across the country. Images of protesters of all races and ages holding “Black Lives Matter” signs fill our news feeds. Voters demand their elected officials do something about it. Corporations of all sizes make public statements in support of the movement and pledge millions of dollars to social justice organizations.

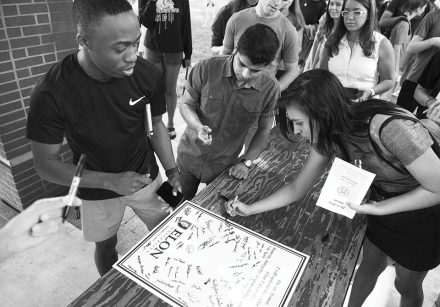

At Elon, Black community members and allies also ask for action to end systemic racism on campus and beyond. They send messages to President Connie Ledoux Book and other members of senior staff. The university announces a series of virtual conversations featuring administrators and Black students, faculty, staff and alumni, which begin June 11. Almost a week later, on June 19, dozens of alumni and students take to social media to participate in #BlackatElon, a virtual protest organized by Nichelle Harrison ’04 L’09. They share stories of racism, macro and microaggressions or just indifference they encountered while at Elon. They also ask their alma mater to do more.

Many more conversations follow, some in private, others on comments sections of social media platforms. The results of these listening sessions, conversations and comments, in conjunction with feedback from the Elon Black Alumni Network and other campus stakeholders who had been working on issues of diversity, equity and inclusion for years, lead to a university announcement on July 8. “Action. That’s what most of you have called for to make Elon a more equitable and welcoming community,” President Book says in a video message to the community that day. “A university where Black students, faculty, staff and alumni thrive and succeed. A university where our commitment to respect for human differences found in the university’s mission statement is fully realized. I agree.”

As part of that message, Book announces five initial action steps with the promise of more to come, all centered on human dignity and diversity. A second announcement comes three and a half weeks later, this time by Randy Williams, who was promoted to vice president and associate provost for inclusive excellence as part of the initial July 8 announcement. In all, the university releases a plan for 15 additional action steps to further advance diversity, equity and inclusion work on campus, ranging from curricular changes, program development and enhancing recruitment of Black students, faculty and staff, to redesigning Elon’s bias response system and expanding aid to Black students. Each action builds on existing work and challenges the university and all its members to commit deeper, work harder and invest more to better support the success of students of color and promote a richer and more just intellectual community for everyone.

Ongoing trajectory

It’s not that there hadn’t been any diversity efforts at Elon before the summer of 2020. The university’s strategic plans have achieved greater diversity and inclusion across the board. Theme One of the Elon Commitment, which guided the institution for 10 years and concluded in 2019, centered on achieving an unprecedented commitment to diversity and global engagement. It resulted in an increase in the number of students, faculty and staff of color, going from 11 percent to 19 percent, 11 percent to 20 percent and 18 percent to 24 percent, respectively. The four-year graduation rate for students of color went from 75 percent to 78 percent, placing Elon in the top 6 percent of institutions nationwide, according to The Education Trust.

On the programmatic front, the Multicultural Center became the Center for Race, Ethnicity and Diversity Education so it could offer expanded support and programming for African American/Black, Latinx/Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American, Alaskan Native and other multiracial groups. Other initiatives launched during that time support LGBTQIA, first-generation and faith-based communities. Among those initiatives was the creation of the Center for Access and Success in 2014, which brought together the Odyssey Program for talented students with financial needs; Elon Academy, a college access and success program for Alamance County high school students with no family history of college attendance; and “It Takes a Village” Project, a literacy and tutoring program serving hundreds of children in the Alamance-Burlington School System.

The newly launched Boldly Elon strategic plan continues this trajectory with plans to further increase the percentage of students, faculty and staff of color. It aims to bring the total number of Odyssey Program scholars to 400 and create a greater sense of belonging, access and support during the next 10 years. These are aspirational goals, says Williams, that call for investments into human resources and programs, and take time to be fully realized. But the events of the summer prompted the institution to accelerate that work. “We wanted to engage, listen, have constructive conversations,” he says. “From those conversations and what we wanted to do resulted these steps largely related to anti-racism.”

Using a racial lens in developing Elon’s next steps was critical for Williams. From reading levels in elementary schools and high school graduation rates to home ownership, mortality rates among pregnant women and incarceration, when one looks at data across systems in society, he says, Whites have better outcomes than people of color, with Blacks and indigenous groups generally at the bottom. “If that is so true across the board, if there is so consistent of a stratification across society,” he says, “we need to acknowledge this occurrence and live up to our mission in response if we really want to graduate students who will change the world.”

For years, Sandra Reid ’85 has seen Elon as an institution struggling like many others to meet the needs of minority populations. When she joined the human service studies program full time in 2006, she was the only Black faculty member in the department and one of a handful across the university. It was not that much different from when she was a student in the 1980s. “It’s been a very slow process,” she says, adding she has seen growth in other spaces, such as student life and professional staff. She welcomes the latest initiatives and sees them as necessary in the midst of the turmoil the country is in but cautions the institution not to be reactionary. “I hope we don’t have to continue to have Black men dying on the streets to precipitate change,” Reid says. “I hope we genuinely take on these values. They have to become our values, not in the moment but true values of the institution. It should naturally and authentically happen.”

It’s a sentiment shared by others. Jumar Martin listened intently to all the announcements Elon made this summer. The sophomore computer science and economics double major knows the institution is working to improve the experiences of Black students, but he wonders about the timing of the announcements. He wants to believe Elon’s actions were not just an attempt to save face when confronted with the deaths and unintentional martyring of Black people across the nation. “Treating African Americans better is in vogue. When it is not in vogue, what do we do?” he says. “I want to see Elon continue to focus on the societal ills that are not in the vision of society. I want to see Elon continue building excellence that recognizes us nationally as an inclusive campus.”

He applauds Elon’s efforts to confront its own past, work he was involved in this past spring as a student representative in the Committee on Elon History and Memory, but wants to see that same dedication applied to everyday things that define the Black experience at Elon. He also doesn’t want the emphasis on the Black community to leave other underrepresented groups even further behind. He is taking it upon himself to be part of the solution. “I want to be able to further the conversation, be able to create policy at Elon and nationally to improve the conversation around diversity, equity and inclusion,” he says. “I see myself as someone who has to do this. If I am able to bring other people with me, I want to do that.”

Ongoing struggles

Like many students of color, Martin knew before coming to Elon that most of his classmates were not going to look like him. He knew he had to make his own way if he wanted to thrive on campus. He found a home in the CREDE, a space where he can be himself, where he can learn about the experiences of other students who came before him. He has also experienced the hostility that comes with being Black in Alamance County, where almost 74 percent of the population is White. “I’ve stayed in the bubble,” he says, referring to the campus, “but we experience Burlington since we are an open campus. You have trucks that go by and yell obscenities to students of color. It’s a concern. It’s been a concern and it continues to be a concern.”

Akilah Weaver ’00, who took the reins as EBAN president earlier in the fall, understands Martin’s skepticism all too well. Black alumni had been advocating for years for Elon to seriously invest in increasing the number of students, faculty and staff of color. And while she has seen progress, she knows there is much work still ahead for the institution. “It is a good start,” she says of the recent announcements. “It’s an opportunity for us to hold Elon administrators accountable.” Weaver appreciates President Book’s commitment to having the pendulum swing in a direction that embraces all cultures while still focusing on the Black student experience at Elon. “It took 2020 to show us the needs, the things that we were missing,” she adds. “This is just the beginning of so much more that Elon is going to need to do to attract great Black students.”

Williams agrees with those who want to see Elon do more for the Black community and for all students of color. “I am an administrator here, I’m an employee, but first and foremost I am a member of a marginalized group that has been disadvantaged,” he says. “This is personal work for me. There is so much more we have to do. But the way systems often support disparities, there is no expedient response to achieving equity. There has to be a deep commitment to a long haul process toward our goals.”

He welcomes external accountability that reflects his own internal demands for action. It’s important for him to hear and acknowledge other voices and to help others along in their understanding of why this is not enough. At the same time, he has to acknowledge those who think Elon has gone too far. For Williams, that is a reflection of fear. This country’s capitalistic mindset that pushes for innovation and a desire to grow, to be better, to aspire to ascend to higher levels, creates a system of oppression by default. “You cannot have advantage without oppression,” he says.

Martin looks forward to the day when that oppression is not resting on his shoulders, when he can be himself in all spaces on campus and doesn’t have to tread lightly while interacting with fellow students. The day when he doesn’t need to be reserved or worry about walking behind a group of girls at night. The day when he no longer has to put his registration on the visor of his car or be constantly aware of where a police car might be. “I shouldn’t have to be afraid of the police. And I am not, but you never know. My dad doesn’t want to bury his son,” he says. “It’s incredibly subconscious; it weighs down in ways you don’t know because this has been your life since you’ve been born. It has become second nature. It has become a part of you, and it should not be.”

Ongoing work

President Book knows this is the painful reality for many Black members of the Elon community. It’s something that motivates her to continue working toward a more equitable and inclusive community for all. “Our Black community is suffering and I am carrying their stories with me as I work to advance excellence at Elon,” she says. “My hope is to make diversity, equity and inclusion a natural part of everything we do as an institution and to provide education on these topics so that students graduate from Elon with this essential knowledge and understanding as they prepare for their professional journeys. Only then can we fully live out our mission.”

Williams says experiences like Martin’s are a reminder that no matter what we do as an institution, we are still influenced by what happens in the nation. He wishes he had the grand answer. There is so much historical trauma that has been passed down, he says, which is stimulated by incidents that occur outside and on campus, whether it’s misogyny or some other form of oppression. There is a need for healing, not just for the Black community, but for all.

In order for that to happen, we have to recognize first that the trauma exists, Williams says, which can be difficult in a society driven by individual ruggedness, where the collective and communal value of trauma gets lost. “We need to ask ourselves, ‘What are the narratives that are not spoken that explain what we see today?’” he adds. “If we can go back to understand that and see how they manifest over time and reinvent over time through policies and practices, then we can try to see a different narrative from what we see in our traditional history books and start getting to some truths.”

That’s why diversifying Elon’s curriculum is so important. Williams points to a foundational graduate course he co-teaches with President Emeritus Leo M. Lambert as part of the Master of Arts in Higher Education program. In it they use “Ebony & Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America’s Universities” by Craig Steven Wilder, a book that deals with the role slavery played in the creation of many of the nation’s Ivy League institutions. For many of the students in the class, Williams says, this is the first time they’re exposed to this important lesson in history. By offering diverse perspectives, greater truths are discovered, which enriches the experience of all students.

Reid agrees. She sees her obligation as faculty in the classroom to bring her own experiences, to have difficult conversations and create unique learning moments. She often gets emails from White students who tell her she was their first Black teacher. “I am glad to be at Elon right now to be part of this change because I know what it’s going to mean for the world,” she says. “Because I am teaching students who want to work in helping professions, they are going to meet all kinds of people; they are going to affect other people’s lives. If my students can have a diverse and broad experience, then it is going to be a better experience for those they come in contact with.”

Williams is keenly aware there is still a long road ahead. While it’s true Elon has improved the graduation and retention rates for students of color, those same students are languishing in areas of acceptance, belonging and other thriving experiences, he adds. And yet, they perform strongly in terms of job and post-graduation placement. “Imagine if they were feeling a greater sense of coming alive with all the gifts and talents they have and not feeling so restricted by macroaggressions, by an ongoing sense of consciousness of how they are speaking to fit in. If they felt a greater sense of acceptance, less discrimination,” Williams ponders, “what might they be accomplishing then for us as a campus and as a society? What great ideas might come from them? What innovations, what ways we might see our world better?”

These questions motivate him every day and give him hope, though he is aware of the brutal realities that exist. He is aware there are those who are unwilling to give up their power for the greater good. Yet, he is determined to ensure every person at Elon clearly sees the role they can play in this diversity, equity and inclusion work. “We have to create a shared vision of what we want for inclusive excellence at Elon. It needs to be developed well and communicated broadly so people across all units see themselves in it,” he says. “I am a systems thinker. My role is a broker of resources, programs and people so we can have a constellation of resources that will be more systemic to respond to the systemic issues that we face.”

As an alumna and EBAN leader, Weaver sees her role as a support for Black students and an advocate to keep the administration accountable. She is optimistic the future will bring change for the better. “As we move to making these changes, even though it’s to help with the betterment of Black students, it’s going to help attract better students altogether,” she says. “The investment that they are making is going to be so overwhelmingly rewarding.”