Evan A. Gatti, associate professor of art history, presented “Legacies of Privilege: Making Meaning for Medieval Manuscripts” at the 46th annual Sewanee Medieval Colloquium.

Evan A. Gatti, associate professor of art history, presented “Legacies of Privilege: Making Meaning for Medieval Manuscripts” at Privilege and Position, the 46th annual Sewanee Medieval Colloquium. The conference is sponsored by the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee, and was held remotely on April 9-10, 2021.

For four decades the Sewanee Medieval Colloquium has brought scholars from across North America to the neo-Gothic campus of The University of the South for a shared conversation about the state of medieval studies. The small size of the colloquium allows for very few concurrent sessions and each session is assigned a respondent who receives the papers in advance and offers prepared remarks that weave individual essays into a larger discussion.

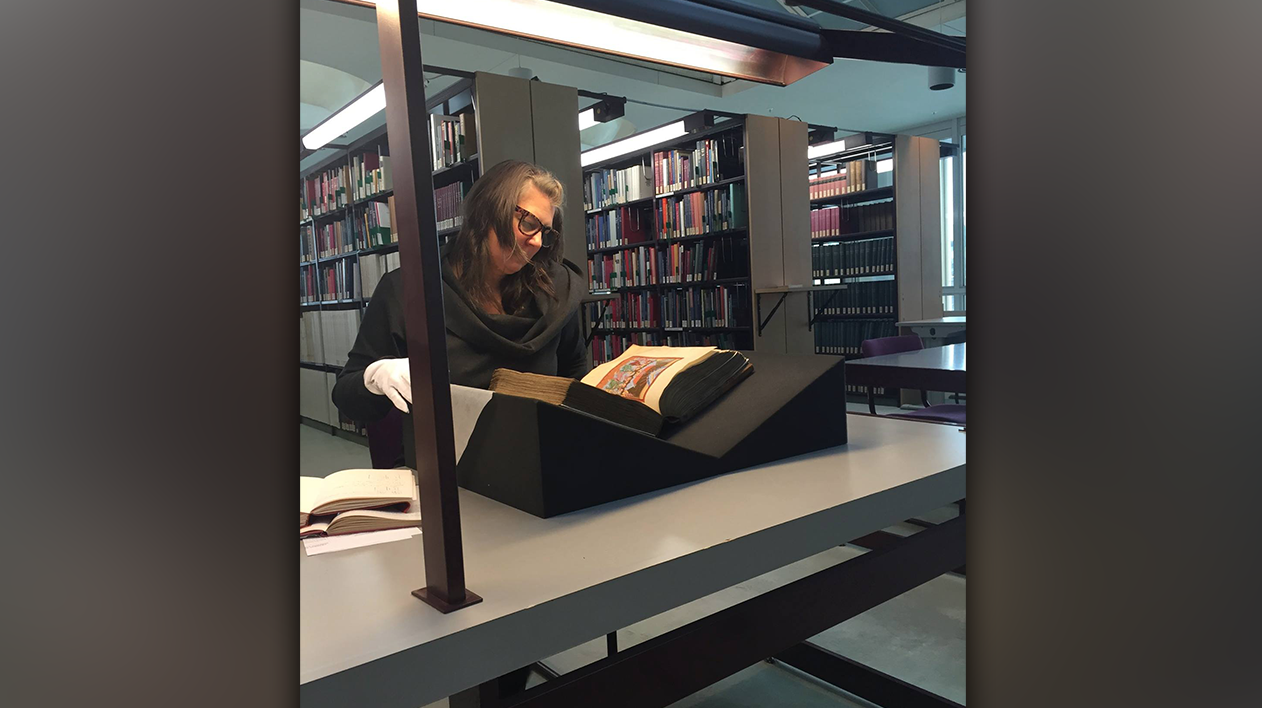

The 46th convening of the Sewanee Medieval Colloquium is dedicated to themes of Privilege and Position. Gatti’s paper for the colloquium, “Legacies of Privilege: Making Meaning for Medieval Manuscripts”, examines how the differences in her ability to access two groups of manuscripts, each belonging to a specific bishop and held in distinctly different contexts, changed the shape and scope of her scholarship. She will suggest that telling the stories about how scholars access the objects they study is a service to colleagues now and in the future. When scholars neglect to document the process or see privilege in how they look at medieval manuscripts, they risk misrepresenting important parts of their approach. Like preserving the data of an archeological findspot, the contexts in which scholars see a medieval book, the layers of permissions required, the other things they see simultaneously, whether they saw the original or facsimile, all affect how future audiences understand and build from their work.

Gatti concludes by arguing that when scholars neglect to reveal how they see the objects of their study, they ignore the privileges that characterize how one experiences a discipline. They suggest that the research process is neutral, that good work will prevail, and the truth will be revealed. We know that is not the case. One’s impact on a field is not shaped simply by diligence, but by access, privilege, and process.