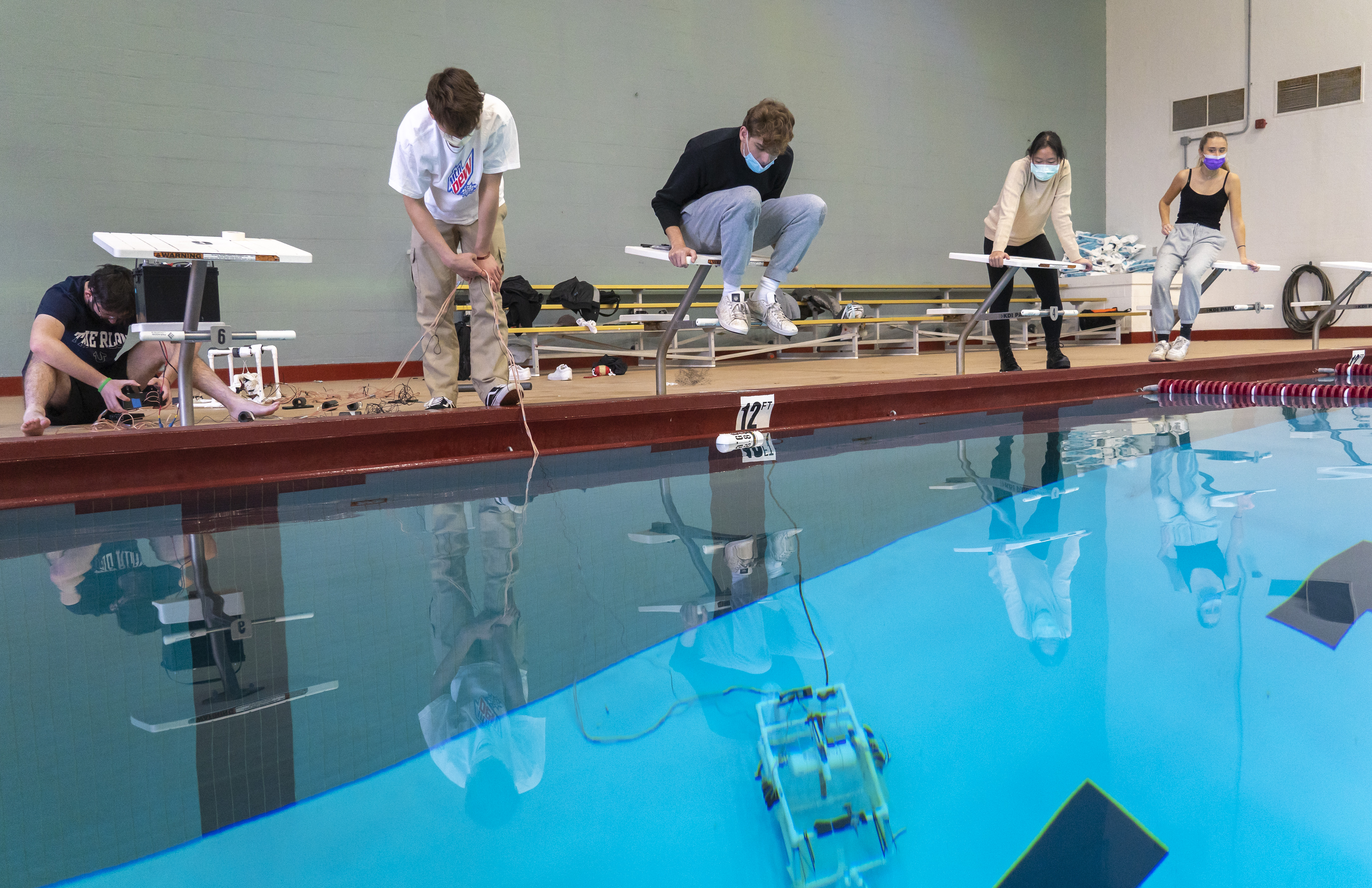

Students in EGR 1210: Grand Challenges in Engineering 1, built remotely operated vehicles and tested them in Beck Pool during finals.

Your assignment: Build a remote-controlled vehicle that can scour the ocean depths, tag creatures found there for future study, gauge water conditions and remove man-made debris.

Your base materials: Three 3-inch propellers, zip ties, some foot-long pieces of PVC pipe, electrical wire and all the ingenuity you can muster.

Yes, you may use duct tape.

This was the basic challenge presented to dozens of first-year engineering students as their final project in EGR 1210: Grand Challenges in Engineering I. In designing their remotely operated vehicles — or ROVs — teams of students had to devise which extra materials would help their PVC-framed prototypes best perform the checklist of tasks at the deep end of Beck Pool.

“We came up with a lot of different prototypes, and then we analyzed which ones worked and didn’t work. It was a lot of trial and error,” said Anna Kauffman ’25.

The first-year Grand Challenges courses (engineering majors take EGR 1230: Grand Challenges in Engineering II in the spring) are built around the National Academy of Engineering’s 14 Grand Challenges for Engineering in the 21st century. They include initiatives around solar energy and cybersecurity, health informatics and medicine, access to clean water and more. The ROV assignment is based on Grand Challege 14: Engineer the Tools of Scientific Discovery.

Testing their designs meant experimenting in a large tank in the Hampl Workshop and, in final stages, in Elon’s fountains.

But conditions in a pool and a fountain differ more than you might expect. Electrical wiring fails more often in open water. Joints come unhinged as a vehicle moves against the small currents in deep pool. Increased water pressure affects buoyancy and propellers’ efficacy. That means real-time troubleshooting poolside, with teams taping, tying, cutting and rebuilding their ROVs under the pressure of a time-limit.

Jake Dyer’s team used the head of a small rake to carry tags to and from the model whale shark at the bottom of the pool. Just before their plunge, the rake attachment broke.

“We had to use electrical tape to wrap around it. Then we had to adjust the buoyancy. It was hard to bring it back up from underwater but fixing all that on-the-fly worked in our favor,” Dyer said.

The ROV project is valuable in developing thoughtful engineers from several angles, said Assistant Professor of Engineering Will Pluer. Besides from being fun to create, they are a model of hands-on collaboration. Students learn basic circuit-building and soldering, and make iterative improvements as they test for crucial balance and buoyancy.

“The ROV is something students have probably never done before, and most haven’t even seen something like it. This means they don’t bring any preconceived ideas to it and have to figure it out themselves,” Pluer said. “The thinking through and changing designs on-the-fly poolside in this project are particularly challenging to students who are methodical and want to get everything just right. Quick problem-solving to finally achieve an objective can be really rewarding, though.”

Parris Lowery ’25 said the course and project taught him time-management skills and the opportunity to look ahead to future projects and challenges as he pursues an engineering degree with a biomedical concentration.

“I’m glad it’s finals and I’m ready to overcome this challenge,” Lowery said. “We knew we had to get this done, and we came out a little bit ahead of schedule so this was good.”