Biochemistry major Anna Sheinberg '22 and her mentor, Assistant Professor of Chemistry Anthony Rizzuto, used laser spectroscopy to analyze aqueous carbonic acid, vital to maintaining pH levels in our blood. The pair also prepared a future collaboration between the University of California, Berkeley and Elon.

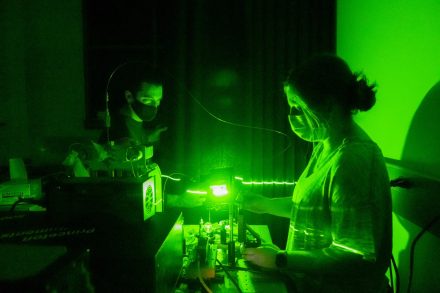

An eerie lime-green glow filling the room, Anna Sheinberg ’22 sets the laser, cuts the lights and ushers a clutch of observers into a third-floor hall of McMichael Science Center.

Closing the lab door behind her, she assures us that in a few minutes the observation of an aqueous-phase chemical reaction that takes place within milliseconds will appear on a screen. Inside, the system replicates the formation and breakdown of carbonic acid molecules over and over, the laser mapping the molecular process in real-time.

“The aqueous carbonic acid molecule was only confirmed in about 2014. We had suspicions about it, but it was hard to catch,” Sheinberg, a biochemistry major, says. “Raman spectroscopy exploits the vibrational frequency unique to each molecule. Based on the types of bonds present and which atoms are present, each molecule will quite literally wiggle a different way, and we’re able to see the wiggles in the spectrum just like this.”

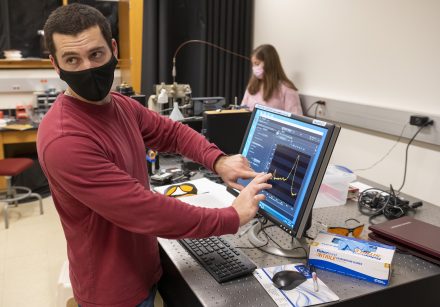

She and her mentor, Assistant Professor of Chemistry Anthony Rizzuto, point to a line graph that looks like the scratching of a lie detector test. Two small spikes show the moment a bicarbonate and acid solution yields carbonic acid before breaking down a split-second later into carbon dioxide and water.

Why all this trouble for a molecule that lasts a millisecond in lab settings? Carbonic acid plays a vital role in regulating the pH of human blood. Understanding its properties could have important implications for advances in medical treatment.

“What we have discovered here is not quite translational to the medical field yet, because we’re working with a water-based solution that’s dependent on the temperature in that room, but Dr. Rizzuto has plans to simulate this in solutions that are similar to human blood,” she said.

“I love research. I could talk about this all day.”

By the time she graduates this May, Sheinberg will have presented this research at the American Chemical Society’s Spring 2022 conference and drafted the manuscript for a journal publication. With Rizzuto, she also has laid the foundation for future research collaboration between Elon and a team at the University of California, Berkeley.

None of this is what she imagined when she arrived here four years ago, which makes her emergence as a research chemist a quintessential Elon story.

“At any other school, I would not have been a chemistry major,” she said.

Sheinberg expected to follow in her Austin, Texas family’s footsteps as a pre-medical student. Her sophomore year, she enrolled in Rizzuto’s general chemistry course and the “happy accident” instantly changed her trajectory. “You could tell that he loved teaching the material and he cared about us,” she said. Chemistry labs became her favorite time of the week. Three weeks into the course, she declared a biochemistry major.

“I can’t give enough credit to Dr. Rizzuto for supporting me academically, in the lab and as a person. Elon loves to boast about the quality of student-faculty relationships and he’s the epitome of that,” Sheinberg said. “This chemistry department as a whole is so incredibly special.”

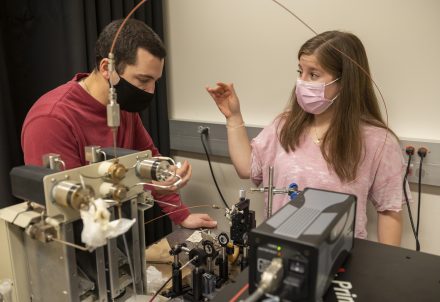

The admiration is mutual. Rizzuto raves about Sheinberg’s “innate abilities” as a researcher and scientist, her persistence in following their two-year carbonic acid analysis to its conclusion and her maturity.

Those gifts were on display when the two traveled to UC Berkeley last summer during the Summer Undergraduate Research Experience to prepare a research project investigating the effects of pH on water droplet evaporation. Using laser spectroscopy, researchers on the West Coast and here at Elon will examine the kinetics and thermodynamics of water evaporation from the surface of micron-sized liquid droplets. That project is a continuation of Rizzuto’s doctoral research at the California campus and unrelated to Sheinberg’s carbonic acid project.

“She was absolutely amazing. Any graduate student should be better prepared than an undergraduate researcher, but Anna’s far above the average undergraduate. She helped train them how to run these experiments,” Rizzuto said.

“I don’t think this collaboration would have happened with just any student. Anna showed faculty at Berkeley what an Elon undergraduate is capable of,” he added.

Looking ahead, Sheinberg plans to spend a year working at a research facility before pursuing advanced degrees in physical or analytical chemistry for a career in professional research. Before departing Elon, she will train additional researchers who will continue advancing the research with Rizzuto.

“It was validating for me to know I could go to lab I’d never been to before and apply what I’ve learned here in the classroom and in research in a new, different area,” Sheinberg said. “This whole process has confirmed to me that I love research. In a teaching lab, you conduct an experiment with a known answer. In a research lab, there is no known answer. Part of the fun is that 95 percent of the time, what you’re doing doesn’t work, so you have to try and try and try to figure out why it doesn’t and find something that does.”