Historian Brandon K. Gauthier ’06 reflects on what makes us different from the worst men who ever lived — and what is fundamentally similar about all of us.

By Brandon K. Gauthier ’06

“And how is it,” Dr. Yoram Lubling asked me during an ethical philosophy course in 2002, “that in the wake of the Enlightenment, after centuries of debates about metaphysics and the human ‘soul,’ Nazi Germany murdered 6 million Jewish men, women and children?” It was not a rhetorical question. It was a moral charge. Grapple with man’s inhumanity to man. That moment reverberates in my mind — a brilliant professor in a classroom in Powell, 20 years ago, demanding to know why homo sapiens, after 200,000 years of history, still behave with such brutality toward one another.

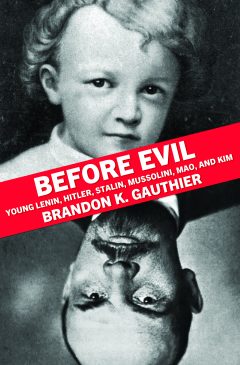

Endless hours of study later, I have written a book about some of the worst men who ever lived: Hitler, Stalin, Lenin, Mao, Mussolini and Kim Il-Sung. I wanted to know about a time in their lives before they were evil — to engage with not only what makes us different from them, but what is fundamentally similar about all of us. To come to terms with the humanity of inhumanity itself — that was my objective.

So I studied their youths. Mothers and fathers. Education. First loves. Favorite books. These men, remember, were once relatable human beings. They emerged from the womb, flesh and blood; and breathed; and cried; and drank milk; and slept; and toddled; and learned to read; and sang; and went to school; and laughed; and wept; and earned good (and bad) grades; and went through puberty; and clashed with Dad; and adored Mom; and wondered what they would be when they grew up (A teacher? A priest? An artist?); and fell in love; and suffered tragedies; and struggled with the complexities of an unforgiving world; and realized that they too would die someday.

Like us, they had the capacity for both love and cruelty from a young age. That perspective is anathema to our need to believe that we’re entirely different. We, who try to live ethical lives and treat others with dignity and respect. But thinking of ourselves as a distinct species from murderous tyrants diminishes our ability to grapple with a conundrum we all share: that the line between individuals doing awful things convinced they are just and people doing awful things knowing they are wrong is not always so clear. At what point can we ourselves become villains without realizing it? How can we guard against as much? The answers begin with considering what we have in common with those we deplore most. Monsters aren’t real. Humans are.

Nothing in the early lives of Stalin and Hitler predestined them to commit mass murder. They had abusive fathers, yes, but good fortune most influenced their early lives. Along with Lenin, Mao, Mussolini and Kim, those two benefited from loving mothers and engaging educations. The earliest origins of the extraordinary suffering they would cause began not with trauma, but from the belief that they could play an important role in changing society for the better. Ideological fanaticism, opposed to only psychopathological traits and crass opportunism, inspired their later crimes against humanity.

To analyze the lives of such men with empathy is the antithesis of their tyranny — not the height of complicity. If we can feel for adolescent Lenin mourning the hanging of his older brother by the Tsar, and teenage Hitler caring for his mother as she died of breast cancer and 20-something Stalin sobbing over the loss of his first wife, we can distinguish ourselves from the monstrous even as we acknowledge our human susceptibility to radicalism and cruelty.

Engage, then, with the humanity of the heinous. Doing so reinforces the recognition that each one of us, under given conditions, can commit terrible acts, big and small, with the conviction that to do so is acceptable, that larger ideological ambitions necessitate as much. But it also reminds us that we can be different by rejecting the tuneful dogmatism of sirens who pull us toward disaster by ignoring, or denying, the humanity of others — even the odious. We can interpret the meaning of human experience, past and present, with compassion, even if it is often lacking in history. Courageous opposition is needed to confront tyranny over the ages. But so, too, is love and mercy.

The onus is on us, Dr. Lubling.

Brandon K. Gauthier ’06 is the director of Global Education at The Derryfield School and an adjunct professor of history at Fordham University. Learn more about his new book — “Before Evil: Young Lenin, Stalin, Hitler, Mao, Mussolini, and Kim” — at BeforeEvil.com.