The Elon alumnus recounts his first day on campus and how Lela Faye Rich guided him to invest in his interests in English, as well as print and broadcast journalism.

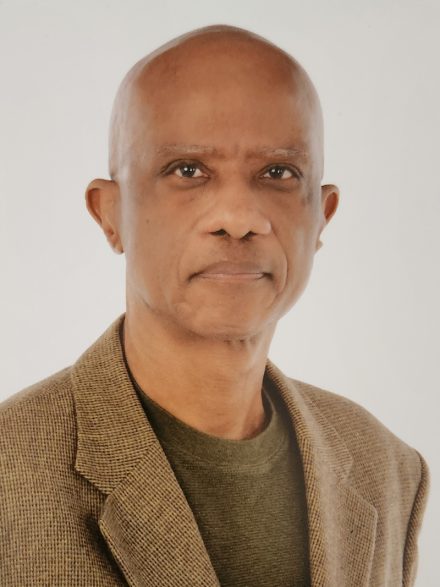

Kevin Wilson ’81 remembers distinctly that he didn’t want to hold up the line on his first day at Elon College.

It was late summer in 1979, and the Glenarden, Maryland, native was settling into campus when he made his way to the auditorium where fate and good fortune led him to Lela Faye Rich. The encounter and subsequent conversation with Rich, who provided academic support at Elon University for nearly three decades, impacted the rest of Wilson’s life.

Wilson had initially considered pursuing a business administration degree.

But noticing Wilson’s course load, Rich inquired about the junior college transfer’s interests and realized he’d be a great candidate for the college’s new English/journalism curriculum. It was then that Wilson asked an innocent question, “What’s journalism?”

More than 40 years later, Wilson still remembers the laugh the two shared. With a line of students waiting, Wilson recalled Rich – who later became associate dean of academic support – detailing the opportunities journalism offered to report and write with the student newspaper, in the yearbook and on radio.

“I told her to stop right there,” Wilson recalled. “I just knew it was a wonderful fit for me as I loved to express myself through writing.”

That one conversation led to Wilson eventually becoming Elon’s first Black male graduate with a bachelor’s degree in English and journalism – a fact that he cherishes more with each passing year. He proudly calls himself a “trendsetter” for his contributions to Elon history, arriving on campus during a tumultuous time for the institution, which was struggling to successfully integrate its student population.

Four decades later, the Committee on Elon History & Memory released a detailed report that focused on the experiences of Black members of the Elon community throughout its history. The report recaps episodes that illustrate anti-Black racism at Elon, several of which occurred during Wilson’s time on campus.

Yet, Wilson fondly recalls individuals like Rich and Professors Mary Ellen Priestly, Robert Blake and Linwood Ferguson taking a personal interest in his studies and success. But that doesn’t mean they took it easy on him.

Wilson enrolled in Blake’s English Literature course and can still remember the red ink that stained his essays and reports. He felt compelled to drop the class until a one-on-one conversation offered him a different perspective.

Blake met the bewildered student not with disapproval, but with advice and direction, pointing Wilson to campus resources to help convert his conversational writing style to something more fitting a published writer. “This professor stimulated me to move forward as a writer – just like a coach,” Wilson said.

Likewise, Priestly didn’t mince words, which Wilson appreciated.

“Dr. Priestly was tough. But I also liked that she was straightforward and honest with me,” he said.

Wilson can still vividly remember when Priestly learned that he could not type, calling it a “cardinal sin” for a journalist to not possess that skill. But Wilson was steadfast that he’d meet every deadline despite his keyboard pecking.

As a student journalist, Wilson fell in love with feature writing and working for The Pendulum, serving under Priestly and Bryant Colson ’80, the first Black editor-in-chief of the student-run newspaper. In addition to features, he also covered news and sports, and penned editorials.

“Journalism really energized me,” Wilson said.

And the young journalist improved, embracing a mindset he developed as a baseball player in his youth – practice, practice, practice.

In hindsight, Wilson said he appreciates the care he received from Elon faculty members. “I learned what constructive criticism was,” he said. “The professors only wanted me to get better.”

Ultimately, Wilson concluded his Elon studies in summer 1981 following the completion of his Contemporary Health Problems course with Coach Ferguson – a class he proudly recalls earning an A in. He later received his degree in August 1981 from Registrar Mark Albertson.

“I refused to leave without a college degree,” Wilson quipped.

Following his graduation, Wilson embarked on a four-decade-long career in communications, working as a writer, publicist and speaker. He has authored news, features and sports stories for local, national and international publications, including Jet Magazine, Educational Pathways Magazine, Sports High School Illustrated, BlackAmericaWeb.com, and Black Athlete Sports Network, among others.

He also started a small marketing business, which he named Sylvester Enterprises, in honor of his grandfather. Norman Sylvester Wilson played and managed a Negro League sandlot baseball team throughout Wilson’s youth, and growing up around the diamond had an impact on Wilson’s professional aspirations.

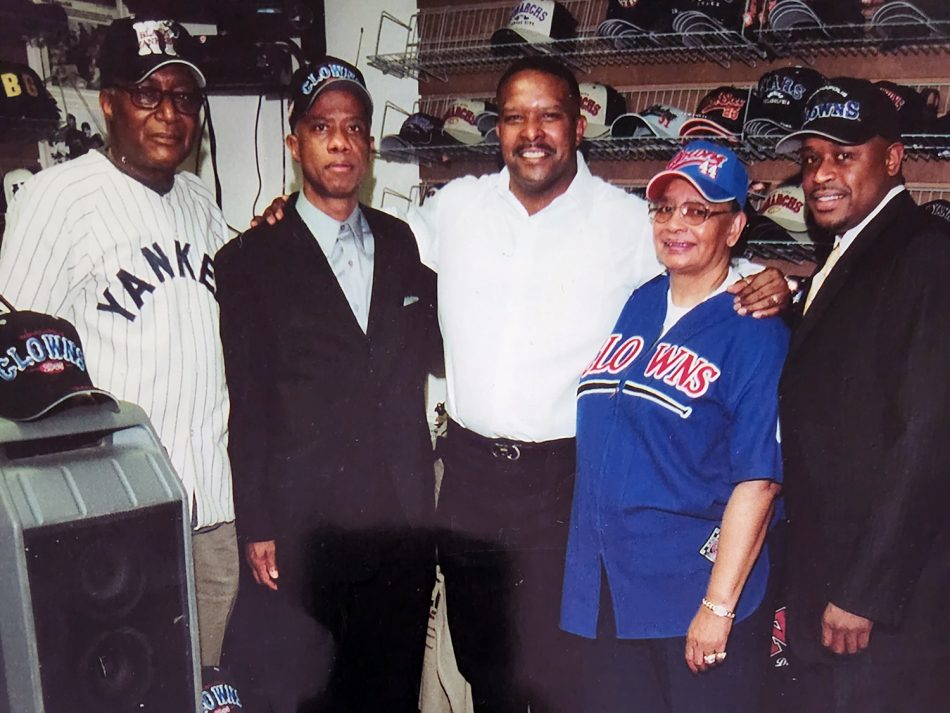

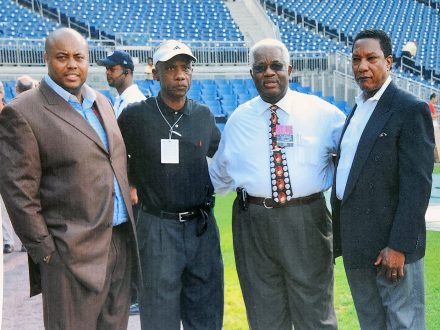

Notably, Wilson represented the late Mamie “Peanut” Johnson, the first and only female pitcher to play in the Negro League. Despite standing just 5 foot, 3 inches tall, she compiled a 33-5 record for the Indianapolis Clowns. Two of Wilson’s proudest accomplishments include booking Johnson in May 2003 to throw out the first pitch at Fenway Park in Boston and interviewing Kevin Durant, the youngest NBA scoring champion.

Wilson also represented Joe Louis Reliford, the world’s youngest player to compete in a professional baseball game, and initiated a campaign for Hall of Fame boxer Mark “Too Sharp” Johnson to have a day named after him in Washington, D.C.

In addition to its marketing efforts, Sylvester Enterprises works to educate and encourage young people, helping them avoid drugs, alcohol and nicotine abuse, as well as gun violence. Several of Wilson’s friends and family encountered these pitfalls and he felt compelled to help others in his community.

Wilson expressed gratitude to his teachers and professors, who encouraged him to follow his interests in writing and reporting. It is a career that has fulfilled him.

“I’m a trendsetter,” Wilson said. “It felt good to be a trailblazer in a new curriculum. I am proud to be a part of the legacy of journalists who have studied at Elon and have gone on to educate and inform their communities.”