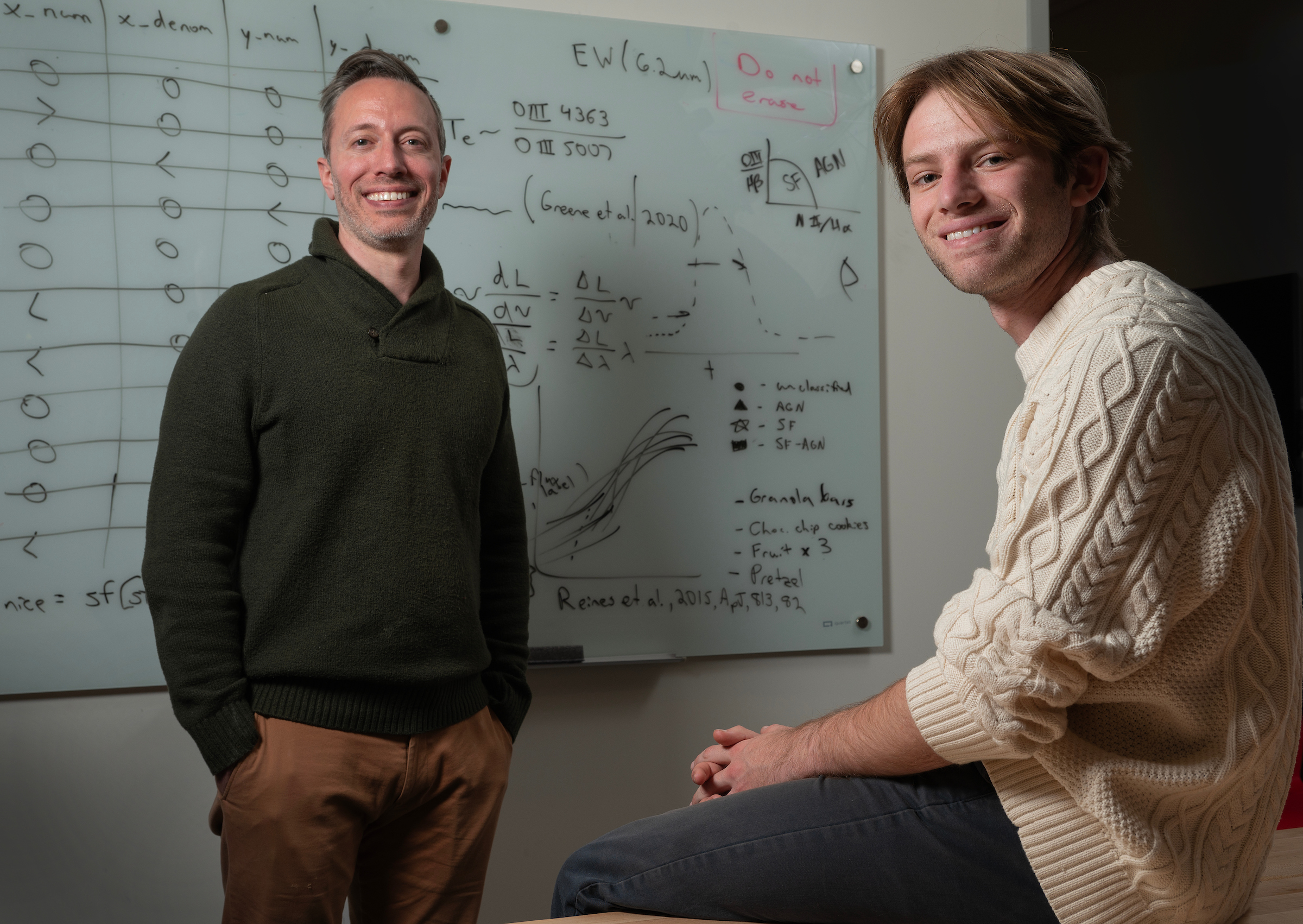

Through his Lumen Prize research, Wels is working with Professor Chris Richardson to learn more about the evolution of black holes and what that evolution could mean for the history of the Milky Way and other galaxies.

When Jordan Wels arrived at Elon University, he hadn’t planned to conduct research as an undergraduate. In fact, he originally set his sights on earning an engineering degree.

But his goals changed quickly as he became enamored with the concepts within the field of astrophysics. For more than two years, he has been working closely with Associate Professor Chris Richardson as a Lumen Scholar to explore the evolution of black holes, research that could contribute to humanity’s understanding of how galaxies like the Milky Way evolved.

“We know very little about the universe and don’t have a great idea of what’s happened during the last 14 billion years,” said Wels, who is majoring in physics and computer science. “Hopefully by seeing a spectrum of all the possibilities, we can have a better idea of what’s happened over these 14 billion years.”

Wels has been able to pursue this in-depth research with Richardson as his mentor through Elon’s Lumen Prize program. The Lumen Prize is Elon’s most prestigious award for undergraduate research and awards scholars a $20,000 scholarship to support a chosen research project and allows the scholar to work closely with a faculty mentor on that project for two years. Each year, 15 rising juniors are named Lumen Scholars and conduct research that often produces conference presentations and publications.

Astrophysics, the Lumen Prize, and Elon, for that matter, were not even on Wels’s radar as a high school student in Westchester, New York. He would hear about the university from a college counselor and was hooked after he took a closer look. “I loved the campus and it was incredibly beautiful,” he said. “I also liked the fact that all the classes were pretty small, and so it jumped up on my list pretty quickly.”

Wels arrived on campus planning to pursue a degree in engineering but found himself more drawn to the physics aspects of the field. At the same time, his interest in computer science continued to grow. One of his physics professors recommended that he talk with Richardson, and that conversation put him on a path to the stars (and black holes).

“After he told me what he did, I loved it and I thought it would be great to go and learn what he was researching,” Wels said. “As soon as we finished our conversation, I was starting to do research.”

For the past five years, Richardson has been focused on filling a gap of knowledge in what we know about black holes, which are astronomical objects with gravitational pulls so strong that not even light can escape them. There are around a million small black holes in the Milky Way galaxy alone. Along with these commonly found small black holes, there are supermassive black holes that are typically found at the center of galaxies. Less common are intermediary black holes — those that fall between the two.

“These have been pretty elusive,” Richardson said. “Part of the reason we want to find them is to understand how the supermassive black holes become supermassive, and we can’t understand how they become supermassive unless we know what they were like before they got to that size.”

Wels became fascinated with the work to advance this research, which has broad implications. “We don’t really know how black holes or galaxies evolve,” he said. “But we know that all galaxies contain a black hole a their center and we know that as galaxies grow, so do black holes. If we can get an understanding of how black holes transition through different masses, we can also learn how galaxies transition.”

Wels can now speak at length about the core concepts critical to answering these questions and explaining to audiences with varying degrees of comprehension what his research is focused on. But that wasn’t the case when he first embarked on this journey. “My research had a very steep learning curve,” he said. “When I started doing it, I had no background in astrophysics. I was learning about astrophysics before I even took the class for it.”

Richardson said that Wels had already established a firm foundation in physics by the time they began working together, including winning the physics award for first-year students. Wels was a quick study, and he credits the process of applying for the Lumen Prize for advancing his ability to explain concepts and his research in an easily understood way. By the time he submitted his Lumen application, he had a much better understanding of what he was doing and would do with the support of the Lumen Prize.

“I could explain it pretty well even to someone who wasn’t totally aware of astrophysics,” Wels said.

Richardson saw Wels evolve as he became more immersed in the research and pursued the Lumen Prize. “Even if he wasn’t awarded the Lumen, and I was confident he would be, going through the process of writing that proposal, you learn a lot more about the field itself and you learn more about yourself going through that process,” Richardson said. “I think he has a greater appreciation for the writing component in the sciences than he did before.”

Wels has become more independent as his research has moved forward, Richardson said. Richardson and Wels were part of a group of Elon faculty and students who attended the American Astronomical Society in January. “He really knows his own path and where he’s going with things,” he said. “I now act more like a sounding board for ideas rather than telling him where to go.”

That work, which has involved collaborating with colleagues of Richardson’s at other institutions and applying for computing time on the supercomputers necessary to do this research, has evolved as Wels has narrowed his focus. He’s been examining the makeup of gases that are not hydrogen or helium around black holes. “It’s been focused on finding a relationship between those two, and that, at least as far as I know, has not been published,” Wels said. “As soon as we created that relationship, the research took a pretty big turn and I think it’s one of the most novel aspects of my research.”

Looking beyond graduation in May, Wels expects to leave his otherworldly pursuits to focus on something much more down to Earth — cybersecurity. He plans to leverage what he’s learned in courses in that area at Elon, and believes that his research as a Lumen Scholar has prepared him to succeed in the field of cybersecurity. “I know in cybersecurity you have to do a lot of research, and while it’s a different topic, the process can be very similar,” he said. “I think having the practice that has come from conducting research and learning the patience that comes with it will definitely help.”

So is he done with physics? Not likely. “Hopefully after a nice long career in computer science, I can end it with teaching physics,” he said.