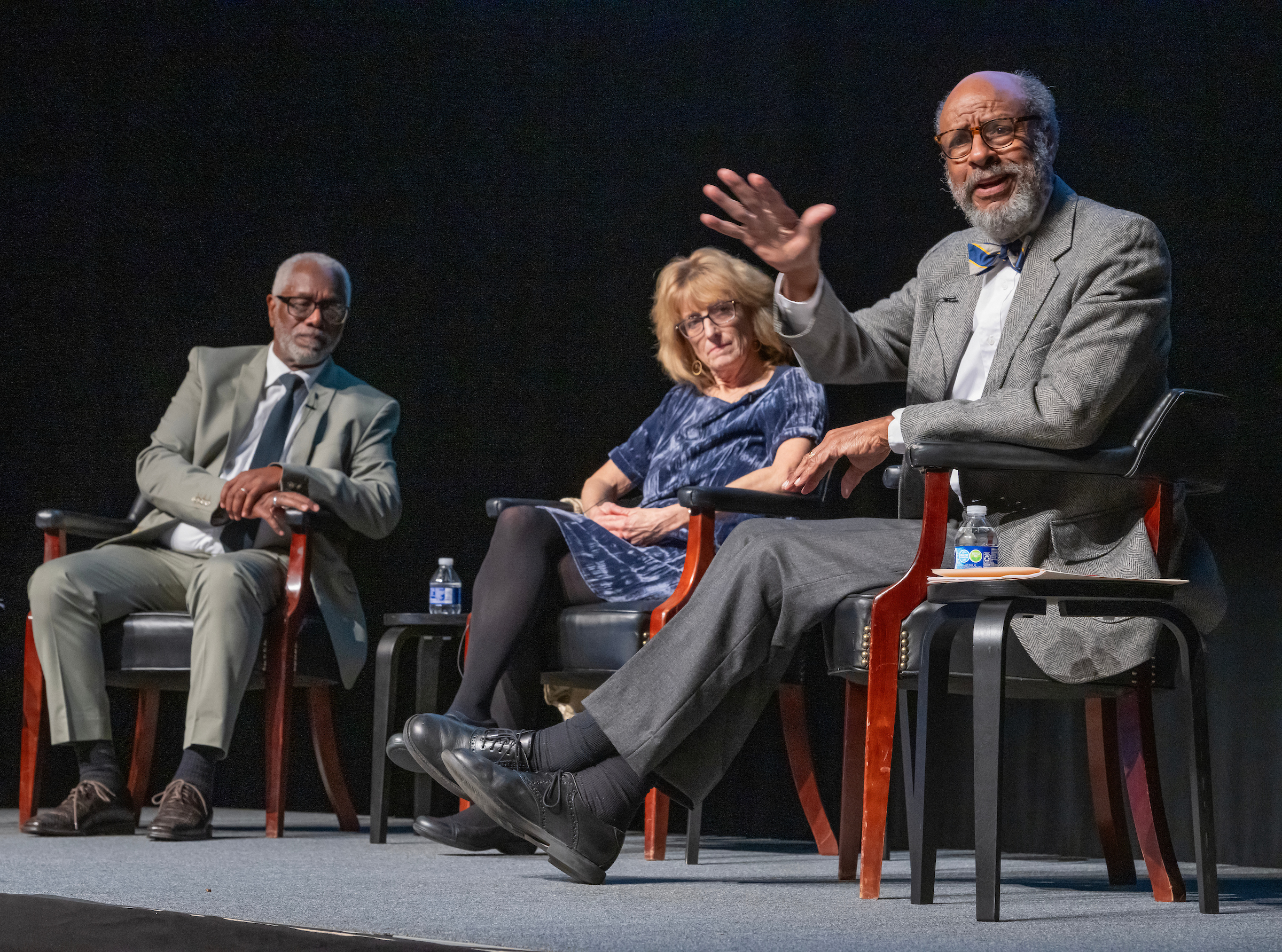

Authors Herb Frazier, Marjory Wentworth and Bernard Powers shared their perspectives in the Martin Luther King Jr. Commemorative Lecture on Monday, Feb. 26, in McCrary Theatre.

The horrific murder of nine church members inside Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, on June 17, 2015, left many in the surrounding community and nationwide feeling powerless. Gun violence had claimed the lives of people gathered peacefully to engage in an evening Bible study in a house of worship, with the person pulling the trigger motivated by racial hatred and a belief in white supremacy.

In response, Marjory Wentworth penned a poem, “Holy City,” in which she wrote that “as bells in the spires call across the wounded Charleston sky, we close our eyes and listen to the same stillness ringing in our hearts, holding onto one another like brothers, like sisters, because we know wherever there is love, there is God.”

Wentworth, a former poet laureate of South Carolina, shared Monday night in McCrary Theatre to those gathered for the Martin Luther King Jr. Commemorative Lecture that writing that poem was a first step toward joining with journalist Herb Frazier and historian Bernard Powers to tell a much larger story about how historic forces led up to the tragedy and how forgiveness and the hope for reconciliation can lead to healing. “There certainly was a larger story and we all wanted to do something to help,” Wentworth told the crowd Monday night.

Wentworth would connect with Frazier, who would then enlist the help of Powers in what became a collective effort to try to make sense of the tragedy and discover a way forward. “The opportunity to participate with Herb and Marjory on this project was in part an act of attempting to empower myself to do something that would be useful in the face of this tragedy,” Powers said. “Also, I hoped that the final product would empower the members of our community and others who were interested in understanding.”

During their discussion, the trio of authors who wrote “We are Charleston: Tragedy and Triumph at Mother Emanuel” provided a broader context for the legacy of the Rev. Martin Luther King, noting that King’s vision went beyond the “I Have a Dream” speech delivered during the March on Washington in 1963 to become a broader push for social justice for Black America. Affirmative action, economic empowerment, health care as a human right were all advocated for by King before his murder in 1968.

However, advances toward equity have been met with a backlash by those who view advances for minorities as an erosion of the rights and privileges of those in the white majority, Wentworth noted. Those arguments resonated with Dylann Roof, who on that June night in 2017 entered Emanuel AME Church, called “Mother Emanuel” by many, and began shooting. “He was radicalized online,” Wentworth said. “He was fueled by the love of the Old Confederacy.”

Violence against minority groups has been on the rise, with horrific attacks at synagogues and increased violence against Asian Americans, Wentworth said. The number of mass shootings has more than doubled from 2015 (232 incidents) to 2023 (656 incidents), Wentworth said.

Frazier pointed to the high-profile shooting deaths of minorities by white police officers as well as numerous instances of domestic terrorism, the most deadly of which was the bombing of the federal building in Oklahoma City in 1995. The election of President Barack Obama fueled the idea among some that there was an effort to “replace” white people. “The shooter at Mother Emanuel — he justified what he did by saying ‘you people are taking over,” Frazier said.

So how are we to respond to the legacies of slavery and racism that converged with progress toward equity and empowerment so violently within the walls of Mother Emanuel? By not losing hope and by honoring those whose lives were lost in Charleston and continue to be lost to gun violence and racial hatred, the authors said.

Part of the reason Charleston was not marred by riots and violence in the wake of the killings was the act of forgiveness that the families of some of those killed expressed following Roof’s arrest, Wentworth said. She shared about how a number of those who had loved ones killed in the shooting have used the tragedy to advocate more fully for changes in gun laws and for choosing love over hate.

Within Charleston, there are efforts to more fully recognize the continued legacy of slavery and white supremacy but to also move forward. A statue of U.S. Sen. John C. Calhoun, whom Powers noted was “one of the leading architects of the proslavery argument,” was removed from a perch that made it the tallest monument in the city (more than 100 feet tall). Since the Mother Emanuel shooting, the International African American Museum has opened in Charleston at what was once Gadsden’s Wharf, the first destination for more than 100,000 enslaved people as they arrived in this country.

“One of the things that is so important about the museum is that it takes the experiences of Black Carolinians and uses them as a lens for understanding the larger world,” Powers said.

Frazier shared that some members of Mother Emanuel have yet to return to their church as they continue to grapple with the violence that took place there. But there is also an effort to erect a monument to pay tribute to those who died and to express hope for the future. “There is so much physical hurt, but the church moves forward,” Frazier said. “Many of the church members are doing things to try to heal this country, to bring about a reckoning with our past, to try to build a better future.”

Rev. Clementa Pinckney, the pastor of Mother Emanuel, was killed along with his church members that night, and realized that pushing for change could cost someone their life, Frazier said. “As we reflect on Dr. King and Rev. Pinckney, let us commit ourselves to living lives that are worthy of their sacrifice,” Frazier said.