Elon experts weigh in on the state of the U.S. opioid crisis and what can be done to curb it.

By Alexa Boschini ’10

After Dr. Andrew Lamb underwent back surgery to repair a slipped disk, he went home with a bottle of 60 painkillers—a typical post-surgery prescription back in 2009. The pills certainly alleviated his pain after the procedure, but they had other benefits, too. A sense of calm. A blissful feeling.

The prescription came with one refill, so when the first bottle ran out, he got more. When the second bottle was gone, he started an internal debate. Could he convince his surgeon to give him another refill? Should he?

Lamb has been an internal medicine specialist for more than 30 years, including a stint as chief of medicine for the 86th Evacuation Hospital during Operation Desert Storm in Saudi Arabia. He’s seen the perception of prescription opioids in the medical field change drastically during that time, and he’s helped many patients use them safely as their primary pain management physician. But that experience in 2009 was the first time he understood firsthand how easily addictive opioids can be.

Lamb has been an internal medicine specialist for more than 30 years, including a stint as chief of medicine for the 86th Evacuation Hospital during Operation Desert Storm in Saudi Arabia. He’s seen the perception of prescription opioids in the medical field change drastically during that time, and he’s helped many patients use them safely as their primary pain management physician. But that experience in 2009 was the first time he understood firsthand how easily addictive opioids can be.

“I’m a pretty tough guy, and I never thought I could come so close to having a problem. But I came close enough that it scared me and woke me up,” says Lamb, now vice president of medical affairs at Cone Health Alamance Regional Medical Center in Burlington, North Carolina, and medical director for Elon’s physician assistant studies program. “The truth is, after less than two weeks, if that, I really didn’t need it. I could have stopped. But I liked the way it made me feel.”

For years, Lamb didn’t tell anyone about how close he came to addiction, not even his wife. But as the country’s opioid crisis intensified, he felt compelled to share his story, to inform others about how quickly addiction can manifest and to emphasize that no one is immune.

According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, about 11.5 million people misused prescription opioids in 2016, and another 948,000 used heroin. Of the 63,632 drug overdose deaths in 2016, according to the Centers for Disease Control, 42,249 involved opioids—66.4 percent of all drug overdose deaths.

Opioids encompass both prescription medications and street drugs such as heroin. They attach to receptor proteins on nerve cells and deflect pain signals, which makes them effective at treating acute pain. But they also induce euphoria particularly when misused, such as taking more than the prescribed dosage, creating an addictive high. “Opioids work on the dopamine receptors within the brain, which are your pleasure receptors,” Lamb says. “People respond differently to them, but if someone takes something that makes them feel really good, like any drug, they tend to try it again.”

Opioids encompass both prescription medications and street drugs such as heroin. They attach to receptor proteins on nerve cells and deflect pain signals, which makes them effective at treating acute pain. But they also induce euphoria particularly when misused, such as taking more than the prescribed dosage, creating an addictive high. “Opioids work on the dopamine receptors within the brain, which are your pleasure receptors,” Lamb says. “People respond differently to them, but if someone takes something that makes them feel really good, like any drug, they tend to try it again.”

Among the most commonly prescribed opioids are hydrocodone (i.e. Vicodin) and oxycodone (i.e. Percocet), which are used to relieve moderate to severe pain. Hospitals use more powerful opioids like morphine and fentanyl to relieve intense pain for surgical or cancer patients. More recently, some street dealers are mixing heroin with fentanyl, which is 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine, to increase its potency. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), heroin is cheaper and easier to obtain than prescription painkillers. It has similar chemical properties and effects, so when patients who have become dependent on prescription opioids run out of pills, some turn to heroin instead.

Nearly every day for the first few months of 2016, Kerri Sigler ’02 L’09, owner and attorney at Sigler Law in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, was either appointed a new client who was a heroin addict or learned someone she already represented was a heroin addict. Many of them initially became addicted to painkillers prescribed by a doctor. According to the NIDA, about 80 percent of people who use heroin first misused prescription opioids. “If you choose to do drugs, that’s one thing,” Sigler says. “But if you don’t choose to do drugs and you end up a raging heroin addict, I think that’s totally disgusting.”

Emerging epidemic

Today’s opioid crisis can be traced to the 1990s, when there was a major push in the medical field to prioritize pain control for patients. “Under pressure to treat pain more seriously, and with assurances from pharmaceutical companies that patients would not become addicted to opioid painkillers, physicians started prescribing them at higher rates,” says Susan Camilleri, an assistant professor of political science and policy studies at Elon who specializes in health policy.

New drugs like OxyContin, which releases oxycodone slowly over a 12-hour period, hit the market and were thought to be less addictive than traditional painkillers. In 2007 Purdue Pharma, the manufacturer of OxyContin, pleaded guilty to “misleading and defrauding physicians and consumers” by marketing the drug as a safer alternative to other opioids. The company and three executives paid a total of $634.5 million in fines.

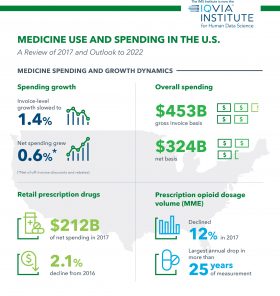

The increase in prescription opioid availability resulted in more misuse of the drugs, and therefore a spike in dependence and addiction. According to market research firm IQVIA, the number of opioid prescriptions skyrocketed from 112 million in 1992 to more than 255 million in 2012. That number fell to about 191.2 million in 2017 as opioid prescription guidelines grew stricter.

Every physician with a Drug Enforcement Agency number, which allows them to write prescriptions for controlled substances, is monitored: how many prescriptions they write, how many pills they dispense at one time, whether they offer refills. “As time went by, we began to see the addictive capability was a lot greater than we thought, and a serious problem was created,” Lamb says. “The whole attitude now toward prescribing opioids is the complete opposite. When you do prescribe them, there are much stricter regulations from the DEA and state boards like the North Carolina Medical Board.”

Community impact

The surge in opioid usage has escalated into a national public health emergency with a profound impact on communities across the country. According to a November 2017 Elon University Poll, about one in three North Carolinians say they or someone close to them have been personally impacted by the opioid crisis. “Social service programs are struggling to keep up with the influx of children of addicted parents,” Camilleri says. “Additionally, evidence suggests that areas with high rates of opioid prescriptions have also experienced large declines in labor force participation rates. The effects of this crisis are reverberating through every aspect of society, leaving virtually no community untouched.”

Lamb says Alamance Regional’s emergency room sees overdose cases almost daily. High doses of opioids lead to respiratory depression; the risk increases when combined with alcohol or sedatives. On average, Lamb says people can become dependent on opioids after using them for a couple of weeks, but for some, it’s a matter of days. “The scary thing is, it’s just totally unpredictable,” he says. “You have no idea who’s going to be affected much more than someone else.”

The influx of opioid-addicted defendants in the court system motivated Sigler to re-establish Forsyth County’s drug treatment court. The county previously had a drug court from 2005 to 2011, when the state stopped funding it. Without a treatment court, the options for addicts convicted of misdemeanors and non-violent felonies were probation and jail. In 2016, Sigler decided to take matters into her own hands. She launched a nonprofit, Phoenix Rising, to raise funds for the program and recruited other attorneys and social workers to help her revive drug court. The court’s first gavel fell Dec. 1, 2017, with Phoenix Rising and the City of Winston-Salem splitting the cost.

“I describe it as just steamrolling everybody; [District Court Judge Lawrence Fine] described it as Kerri threw everyone on her back and off we went,” Sigler says. “It was a pool of participants who were willing in spirit but who didn’t think you could do something in the judicial system unless it came from the top down.”

The drug court is a 12-month, post-plea program available to defendants who are eligible for a probationary sentence and meet certain criteria, even if their charges are not directly drug-related. Sigler says the most common charges are theft and breaking and entering in order to sell or pay for drugs. Lawyers, probation officers, judges, social workers and counselors assist defendants in their recovery efforts. Drug court participants report in person twice a month to update the team on their progress, including their work toward securing employment and safe and affordable housing.

Sigler says the latter is often the most challenging obstacle on the road to recovery. “We like to get tough on crime, but I think that’s stupid. I want to get smart on crime,” Sigler says. “Defendants can look to drug court and say, ‘If I’m going to be on probation anyway, if I’m going to plead guilty anyway, then my sentence may as well come with a whole bunch of free treatment for my addiction. It may as well come with court oversight I wouldn’t have otherwise.’ Drug court is not the solution to the addiction crisis but it’s something the criminal justice system needed to offer if we were going to make any headway with this.”

Finding solutions

Lamb says curbing the opioid crisis requires action at all levels—federal, state and local. In 2016 the CDC published new guidelines for prescribing opioids for chronic pain, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services implemented an opioid misuse strategy focused on opioid abuse prevention, treatment and research. In spring 2018, the North Carolina Medical Society Foundation launched an initiative called Project Office-Based Opioid Treatment dedicated to boosting patient access to opioid treatment and recovery.

At the federal level, in 2016 Congress passed the 21st Century Cures Act, which included $1 billion in grants for states to expand opioid addiction prevention, treatment and recovery support services. At the state level, North Carolina’s Strengthen Opioid Misuse Prevention Act sets limits on the quantity of opioid medications doctors can prescribe. “This is a complex issue that requires a multi-dimensional, coordinated response from all levels of government,” Camilleri says. “Closing the health insurance coverage gap would also have an impact, as treatment options are often unaffordable for the uninsured.”

Grassroots initiatives also play an important role in educating the public about the opioid crisis. In addition to its medical guidelines, the CDC recently issued a report outlining opioid overdose prevention strategies for law enforcement officers, public health professionals, nonprofit organizations and others at the community level. Jennifer Carroll, assistant professor of anthropology at Elon, was the lead author of the recommendations. In spring 2018, Camilleri participated in a workshop with Alamance County commissioners, health care providers, law enforcement, first responders, educators and other community members dedicated to coordinating a response to the crisis locally. She also organized a campus discussion about the opioid epidemic in North Carolina that featured Lamb and Sigler as guest speakers.

Though Sigler initially founded the Phoenix Rising nonprofit to support Forsyth County’s drug court, the organization’s mission has expanded to include awareness campaigns about addiction in general and treatment facilitation. Next, she hopes to create a searchable database of resources to help addicts and their loved ones find treatment options more efficiently. The easiest and most effective thing anyone can do, Sigler says, is speak up. “It is incumbent upon every single one of us as human beings to open our mouths to the people we know who are likely to be prescribed pain pills and say, ‘You can get addicted to those in five days. You need to be careful,’” Sigler says. “It doesn’t matter who they are or how much they can be trusted. You don’t know what effect it’s going to have on a person, so you need to open your mouth and warn them.”