“Bringing the Dead Home: Hindu Invitation Rituals in Tamil South India” is the cover article in the most recent issue of the Journal of the American Academy of Religion

Amy Allocco, associate professor of religious studies and director of the Multifaith Scholars program, recently published a major article titled “Bringing the Dead Home: Hindu Invitation Rituals in Tamil South India” in the Journal of the American Academy of Religion (JAAR).

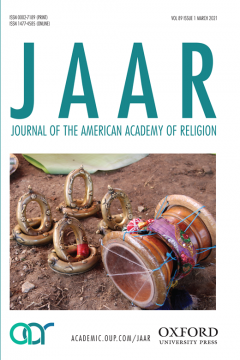

The JAAR is the flagship journal in the discipline of religious studies. One of Allocco’s photos is featured as the cover image. It depicts the percussive instruments that are essential in a range of ritual performances, including ceremonies to deify deceased family members that are the subject of her current research.

Allocco has conducted long-term ethnographic fieldwork in Tamil-speaking South India focused on the broad repertoire of ritual relationships that Tamil Hindus maintain with their deceased kin. She is especially interested in rituals to honor those known as pūvāṭaikkāri, dead relatives who are entitled to be worshiped as beneficent household deities that protect a family. This article presents one Hindu invitation ritual to invite three deceased women back into the world of the living and install them as family deities that she recorded in 2015. Allocco gained access to the two-day ceremony by virtue of her long-standing relationships with the ritual musician-priests who officiate at these performances.

These ritual specialists compel deceased relatives to reenter the world of the living, convince them to possess a human host, and persuade them to be permanently installed in the family’s domestic shrine so that they may protect and sustain the family. Drawn from dozens of such invitation rituals that she witnessed in Tamil Nadu, Allocco leverages this ceremony to demonstrate that predominant scholarly perceptions of death and what follows it in Hindu traditions have severely constrained scholars’ ability to take account of other models for relationships and ritual engagement between the living and the dead.

These ritual specialists compel deceased relatives to reenter the world of the living, convince them to possess a human host, and persuade them to be permanently installed in the family’s domestic shrine so that they may protect and sustain the family. Drawn from dozens of such invitation rituals that she witnessed in Tamil Nadu, Allocco leverages this ceremony to demonstrate that predominant scholarly perceptions of death and what follows it in Hindu traditions have severely constrained scholars’ ability to take account of other models for relationships and ritual engagement between the living and the dead.

Allocco argues that these rites — rather than aiming for an irrevocable separation of the dead from the living, effected through cremation and reincarnation and pursuing the ultimate goal of liberation — are oriented toward eventual conjunction with the dead. Invitation rituals for pūvāṭaikkāris, which are common among particular middle- and low-caste Tamil Hindu communities, reveal a fundamentally different picture than that articulated in the majority of Hinduism’s sacred texts and scholarly accounts.

Allocco believes that these rituals demand that scholars rethink their reliance on the prevailing cremation-reincarnation-liberation paradigm for the Hindu afterlife. The majority of her interlocutors bury their dead, and most articulate discomfort with the idea that they must be repeatedly reborn and deny that their ultimate goal is to achieve release of the soul.

The case study that Allocco features in her article demonstrates that existing scholarly frameworks that rely on high-caste, textual and gendered norms have impeded our ability to perceive how, in some communities, families keenly desire the presence of the dead in the home, the living rely on the dead to cultivate familial prosperity, and kinship relationships between the living and dead are continually negotiated and performed.

The fieldwork that forms the basis for this article was carried out in 2015-2016 as part of Allocco’s “Domesticating the Dead: Invitation and Installation Rituals in Tamil South India” research project. Her sabbatical research was supported by a Fulbright-Nehru Academic and Professional Excellence Fellowship and an American Institute of Indian Studies Senior Fellowship with funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Allocco conducted follow-up field research related to this project in Tamil Nadu in 2018 and 2019.