Altmann’s research project involved collecting and testing 2.5 pounds of cigarette butts and devising a cigarette smoking apparatus to find out which metals are being released by littered butts.

It’s 3:30 p.m. on a Wednesday and, inside a McMichael Science Center chemistry lab, Anna Altmann ’23 is smoking her second cigarette in a half-hour.

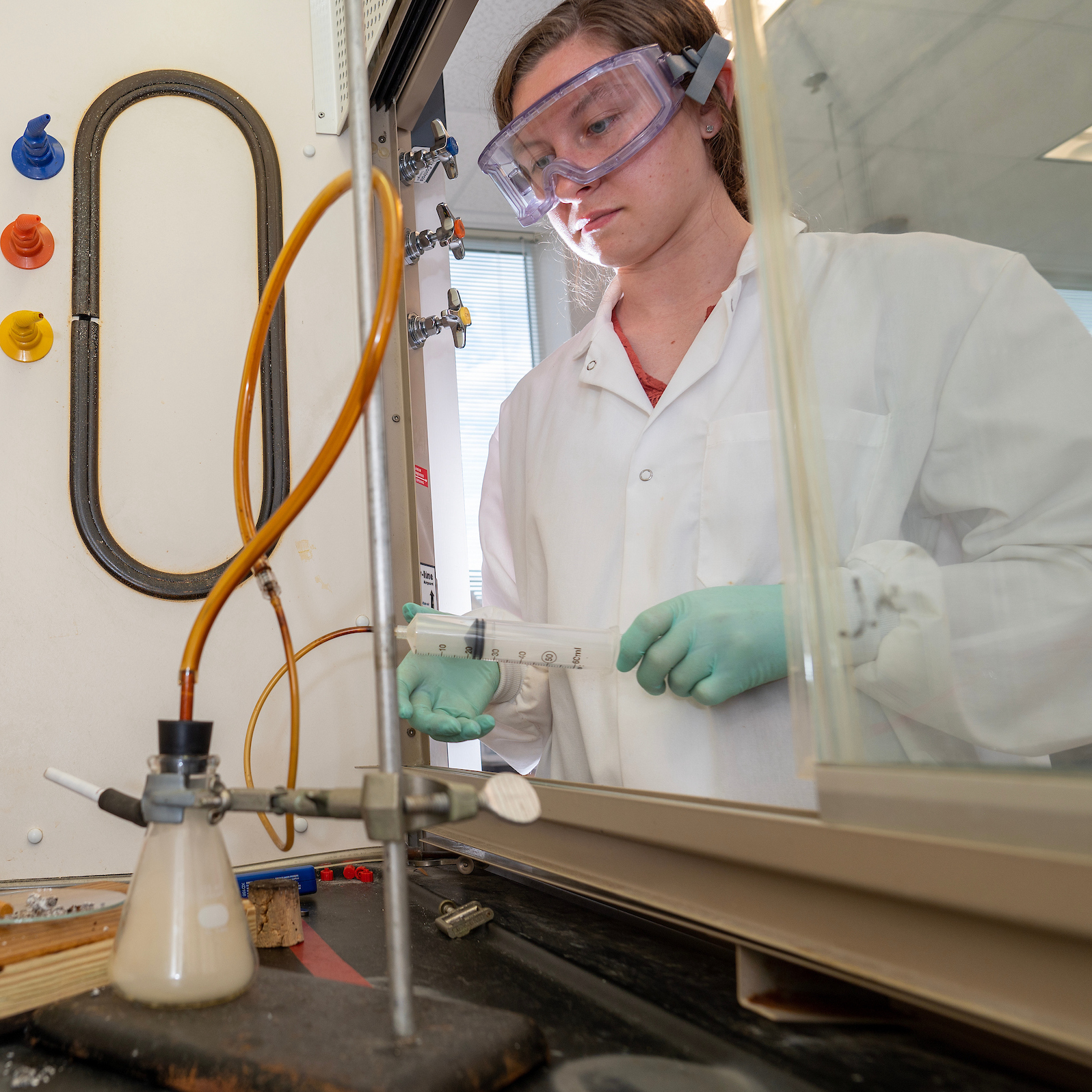

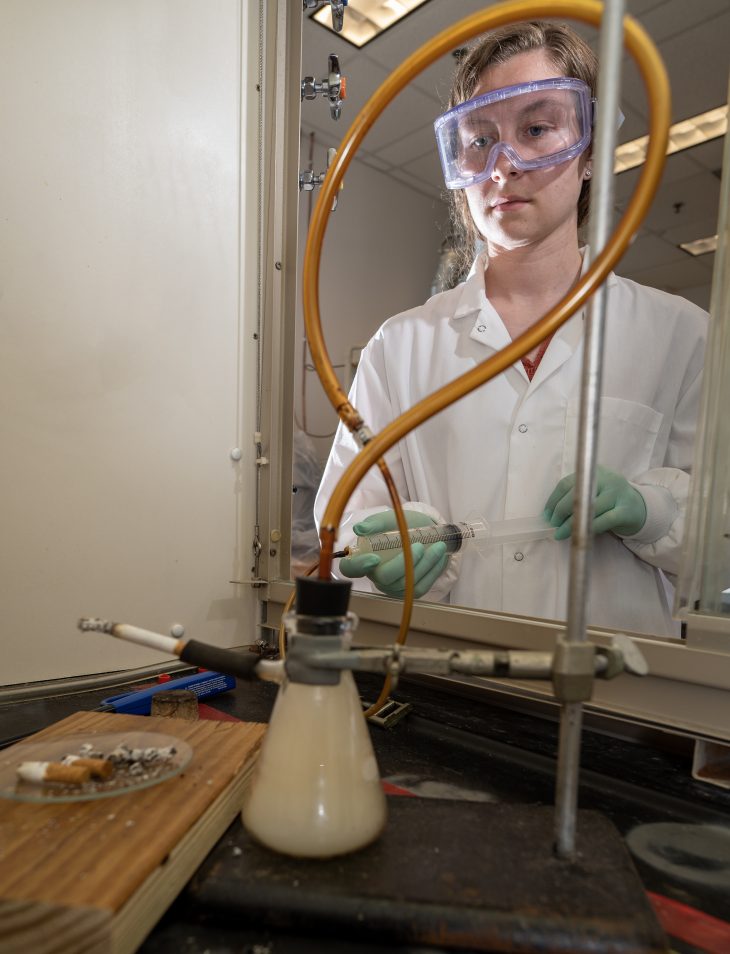

With gloved hands, she places the cigarette into a nozzle attached to an Erlenmeyer flask, lights it and — using a plastic syringe — draws air through the flask and a couple feet of tubing. Altmann leans away from the hood as a faint smell of tobacco smoke fills the lab.

“It’s very smelly, but this just being a couple of cigarettes, it won’t get too bad,” she says.

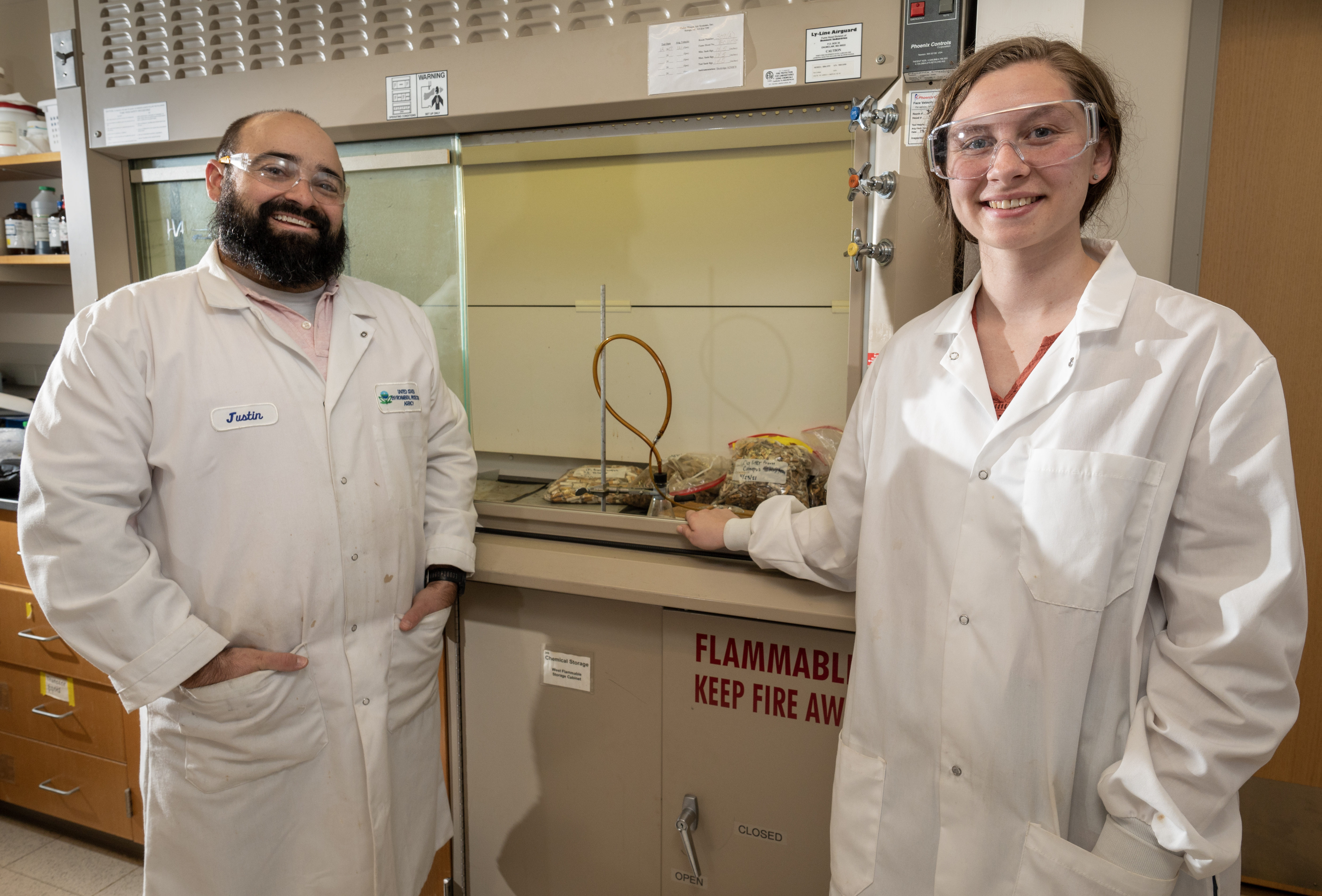

“But if you’re in here for a long time and doing lots of them, you’ve got to schedule a shower after,” her mentor, Associate Professor of Chemistry Justin Clar, says. Altmann nods and smiles in weary agreement.

Scientific research can be a messy process. Sometimes it’s downright dirty.

To better understand how much and what kinds of metals are leaching from and being adsorbed by littered cigarette butts, Altmann knows this all too well. The Goldwater Scholar, Lumen Prize recipient and Honors Fellow has spent the last two years collecting and studying cigarette butts and using her improvised smoking apparatus to create fresh ones.

Cigarette butts are more than just litter. They’re a global problem. Each year, an estimated 4.95 trillion cigarette butts are littered, ending up in runoff, polluting oceans or languishing in the dirt. Once they’re tossed, they do more than linger. All those butts are actively releasing and adsorbing trace metals, influencing the global cycling of these elements.

A chemistry and computer science double major, Altmann became interested in environmental chemistry before college. A native of Burlington, N.C., she completed general chemistry with Clar while still in high school. As an undergraduate searching for honors thesis topics related to chemistry and the environment, Clar — an expert in the study of metals and nanoparticles in environmental systems — recalled questions he’d had about littered cigarette butts since his post-doctoral work with the EPA in Cincinnati.

Altmann dove into existing research and discovered gaps in what had been studied about the release of metals from cigarette butts, namely that cigarettes had been tested in labs but not collected from litter. A light went on and Altmann had the nut of her research question: What and how much are all of these littered butts releasing into or adsorbing from the environment?

“She came up with this comparison on her own. Since then, she’s chosen everything we’ve done with solutions, solvents, time periods and collections, everything,” Clar said.

Altmann’s exploration of that issue earned awards nationally and at Elon.

In her sophomore year, she was awarded the prestigious Goldwater Scholarship, one of the most selective awards in the country given to undergraduates intending to pursue research careers in STEM. She was only the second Goldwater Scholar from Elon to win the award as a sophomore. That same year, she was awarded the Lumen Prize, Elon’s top research award that annually provides 15 rising juniors with $20,000 to advance their undergraduate research projects.

In addition to paying for necessary materials during a period of pandemic-related rising costs, those prizes bolstered Altmann’s confidence in her research and afforded opportunities she may not otherwise have had. She attended the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry Conference, twice attended American Chemical Society conferences — where she will present her research later this month — and traveled to Rice University to give an invited talk.

“Having that money allowed her to network with a lot of people, which is going to open doors for her in graduate school,” Clar said. Altmann has already been accepted to a number of environmental engineering doctoral programs, including those at Yale, Duke, Clemson and Carnegie Mellon.

As demonstrated by the improvised tube-and-flask method of creating fresh specimens in the lab, Altmann went to great lengths to gather enough samples to glean solid data. That included rallying volunteers over Homecoming Weekend to collect butts around and near campus.

“Elon is a non-smoking campus, so we weren’t sure if we would find enough, which is why we collected on the day of a big football game when we thought people might be tailgating. We were surprised how many we found,” Altmann said.

That day, they collected four gallon-sized bags of filters — a few thousand butts weighing in close to 2.5 pounds — in various states of degradation. Altmann spent the next few weeks sorting them by their condition, from freshest to most degraded. She analyzed them for metal content and put others in chemical solutions to test for leaching.

Preliminary analysis shows that cigarette butts are both leaching and adsorbing metals. Sodium, magnesium, potassium, calcium and aluminum were leaching in the highest concentrations. The more degraded the butt, overall, the lower the concentration of leaching. Chemical solutions didn’t play a significant role in how much or which metals leached.

“As of now, the data indicates that cigarette butts from the environment contain between 11 and 16 metals depending on the level of degradation, with the most degraded butts containing metals not found in artificially smoked or less degraded samples,” Altmann said. “This indicates that the butts are picking up metals from the environment, which is potentially problematic because of the balance of naturally occurring metals in soils. Chromium, nickel and lead were in the most degraded butts but nowhere else, and aluminum, iron, and zinc were higher in more degraded butts than in the less degraded butts.”

Some of the leached metals, like aluminum and zinc, can cause health problems.

“We are most concerned about arsenic, mercury and lead, and we are sending samples to another lab for external analysis of those metals. If we find them, that would be more concerning to us health-wise,” Altmann said.

She hopes her future research will involve environmental remediation.

“I’m really interested in looking at how to remove metals from water. In this project, I was looking at how metals enter water from a new source, but I’m more interested in aspects of remediation,” she added.

Altmann initially found the research process intimidating but it resulted in the most rewarding part of her college career.

“Just because something is new to you doesn’t mean you can’t do it,” Altmann said. “I was worried I would fail at research and worried it would be difficult to find a mentor and work on a long project. I’m so glad I pushed through that fear.”

Leaving her comfort zone developed both self-confidence and research skills.

“She’s taken a lot of ownership of the project and I just make sure what we’re doing is in line with the big-picture goals,” Clar said. “It turned into her coming to me and saying, ‘I’m going to do this,’ which is an indicator that, instead of me telling her what to do, she’s directing where it’s going and I’m just making sure we stay on the tracks.

“I don’t have to worry about Anna. She just chugs along and gets the job done.”

As for smoking, Altmann has no plans to pick up the habit and is glad her days of lighting cigarettes in labs are behind her.

“If this project taught me one thing, it’s that I’m surer than ever that I won’t smoke,” Altmann said. “Having to smoke those cigarettes for hours upon hours and seeing the gunk that filled the tubes was disgusting. So, while I have loved my research, I am happy to not smoke anymore.”