Olson spent most of the month of January aboard a 40-foot sailboat on a journey to the icy continent.

Thomas Olson ‘24 knows his way around a sailboat, having grown up around boats and spent time helping man a variety of wind-blown crafts.

But nothing in those experiences completely prepared him for crossing Drake Passage to Antarctica in January. Considered one of the most treacherous bodies of water in the world, Drake Passage lies between the tip of South America and Antarctica and was one of the biggest challenges Olson faced in realizing his dream of making it to the icy continent.

“I’ve had a lot of experience in the realm of boating,” said Olson, an Elon senior majoring in international business and finance. “I’ve always wanted to do something extreme with boating.”

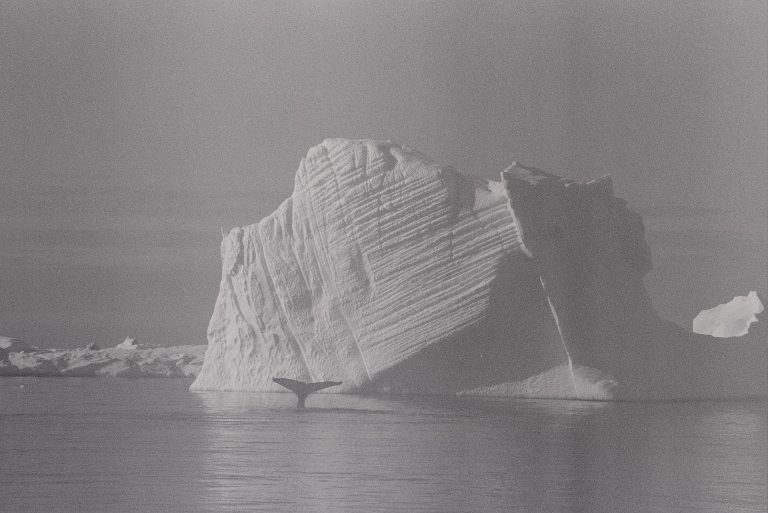

But Olson likely wants to forget the four-day passage on a 40-foot sailboat buffeted by the wind and bounced by the ways on an unforgettable journey to see Antarctica up close. He was part of a crew of six that made the journey in January that gave them an up-close look at abandoned whaling stations, climate research bases and plenty of penguins and whales. While many of Olson’s classmates were spread around the globe, Olson was heading toward its southernmost continent for a once-in-a-lifetime adventure.

“This really has been a phenomenal experience in my life,” Olson said after arriving back on Elon’s campus to begin spring semester. “It’s something I will never forget and was an opportunity that was laid out in front of me that I am so glad I took. It’s pushed my boundaries in ways I never expected it to.”

Olson planned the trip himself after learning his roommates and other friends would be away from campus during Winter Term on various study abroad programs. Olson is well steeped in international experiences, having moved to London when he was 12 and remaining there through high school graduation. His time at Elon includes internships in the United Kingdom and in Munich, Germany, and his studies have focused on international affairs, including a transformative Winter Term program in Japan led by Professor Tina Das.

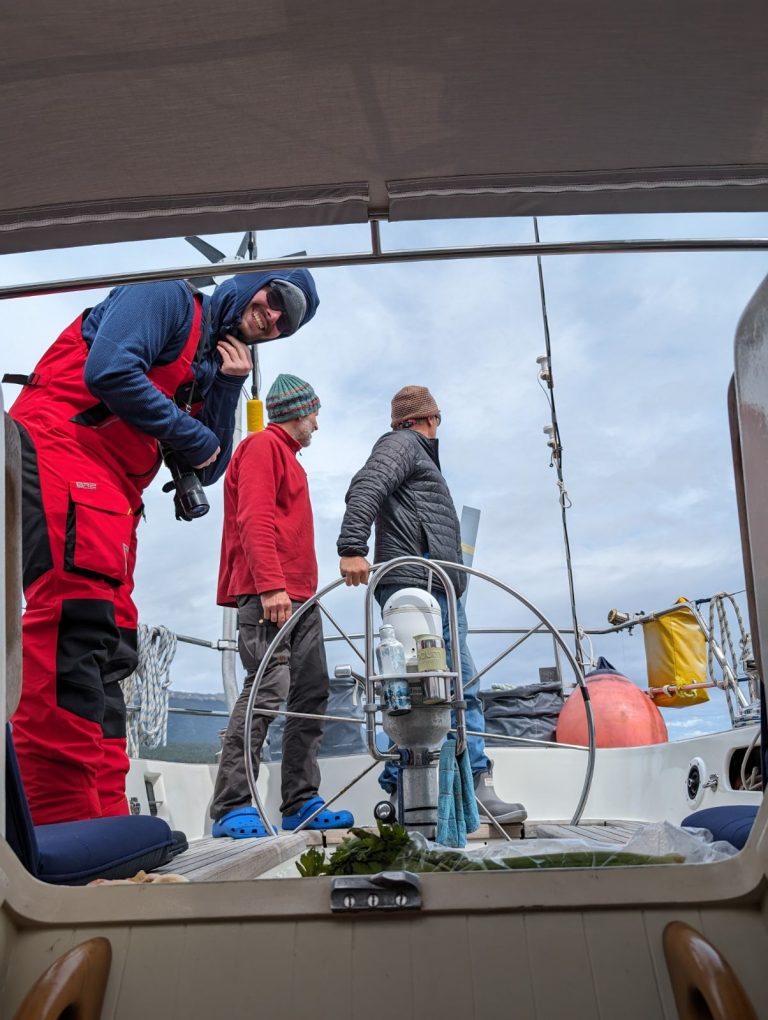

For Winter Term, he didn’t want to just pass the time on campus, and decided to plan and pursue an extreme experience on his own. His experience sailing coupled with a desire to visit South America and an ongoing interest in Antarctica led him to the Sailboat Jonathan, a sailboat based in Ushuaia, Argentina, and captained by Mark Van de Weg, who makes two or three trips to Antarctica each year. Olson secured one of four spots on the boat and arrived in Ushuaia at the end of December.

The journey across Drake Passage

The journey from Ushuaia would include the four-day trip across Drake Passage, about two weeks moving from island to island along the Antarctic Peninsula, and then another five days across Drake Passage. Olson was only allowed a suitcase with no more than 50 pounds of gear, largely consisting of ski gear repurposed to protect him in the cold and wet environment. Including the travel to and from Argentina, “It was a little over one month trip and you have a lot of heavy equipment to bring with you,” Olson said. “I was completely prepared to be quite dirty.”

Before embarking across Drake Passage, the boat docked for two days in Puerto Williams, Chile, where Olson found kindred spirits focused on experiencing one of the most extreme corners of the globe. “All of these sailboats there were part of such a small, tightknit international sailing community,” he said. “German, British, American – people from everywhere were in this little port. Some were going to the Pacific, some were going up to the Atlantic. Some were going to Antarctica. It was so much fun.”

Olson was both excited and nervous as they prepared to set sail, and it turns out, rightfully so. For four days, he battled the effects from the nonstop rocking and rolling of the boat, spending two hours on at watch and then six hours off, during which he tried to sleep. The effect of the rocking and rolling on his body coupled with some side effects from his seasickness medicine made it almost impossible to eat and limited his consumption of water to sips. “You could just never catch a break, so it was very taxing both physically and psychologically,” he said. “The scariest part of it was the fact that if you fall in the water, you have about three minutes” to be rescued, he said. “In 20- to 30-foot swells, all the heavy equipment you’re wearing to keep yourself warm will drown you.”

Arriving at the end of the Earth

After four days, relief, and landfall at Deception Island, part of the South Shetland Islands off of the Antarctic Peninsula. Olson recalls thinking, “Now that I’m actually here, I can start enjoying this and be here. This is where the real enjoyment of the trip begins.”

He and his fellow travelers were able to explore Deception Island, including the remnants of a whaling station first built more than a century ago and gravesites of those who had toiled there. The fog would roll through and create what Olson described as a perfect “horror movie moment.” Portions of the island were littered with massive whale bones or the remnants of smaller whaling boats. Olson was getting an up-close look at a landscape and portions of history that venturers on passing cruise ships could only glimpse from afar.

From Deception Island, the Jonathan would carry its crew to weather and research stations operated on various locations within the South Shetland Islands or on other islands off the peninsula. At the Juan Carlos Antarctic Base operated by the Spanish Army, Olson met with the lead captain, enjoyed a tour of the research station and met with scientists. He engaged with penguin experts, volcano experts and meteorologists.

“The research base was amazing,” he said. “It felt like something out of science fiction, with its heavy equipment and the black sand and volcanic ash.”

Sailing south, they saw a range of penguins — Adélies, Gentoos, Chinstraps (but no Emperors). He learned about how shifts in the ice are impacting different parts of the region and how those changes are affecting penguin populations, some positively and some negatively.

Along their route they stopped at the Port Lockroy research station operated by the British government and Palmer Station operated by the U.S. government. The final stop was at Vernadsky, a Ukranian research station that was notable as the location of researchers who discovered the hole in the ozone layer. The station is known for its joyous celebrations, Olson said, but the mood was much more somber due to the ongoing war with Russia. He did have the opportunity to share some homemade liquor distilled at the base.

From there, the Jonathan turned north and began what would be a five-day journey back across Drake Passage to South America, a trip that was no easier than the trip to Antarctica. As the boat approached Chile in the final stretch, dolphins joined it and swam off the bow as it cruised toward the harbor, in what Olson said was a poetic end to the venture.

The adventure greatly increased Olson’s respect for dedicated sailors and what they can overcome, and left him feeling more confident and ready for new adventures in the years ahead. It was another experience that fits well into his time as an Elon student.

“Elon has given me the time and opportunity to do a trip like this,” Olson said. “I feel like Elon’s focus on international exposure is what sets this University apart. You can’t truly understand cultural diversity unless you live it. “I don’t know any other university that does something like that, or to this extent,” he said.